While the early 00s might have been a far more concrete example of a time when the U.S. was clinging as best as it could to the excesses it enjoyed in the 80s and 90s, Jennifer Lopez chose to go the “Can’t Buy Me Love” route of The Beatles’ pre-antiwar driven 60s with the repackaged sentiment, “Love Don’t Cost A Thing” (incidentally, eventually reused for the remake of the 1987 movie Can’t Buy Me Love for 2003’s Love Don’t Cost A Thing).

Released as a single in late 2000 from her then forthcoming second album, J.Lo, many had speculated that the lyrics were intended to throw shade at her boyfriend of the time, Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs (he was still Puff Daddy then, and maybe always will be), for his overly materialistic nature. But then, Lopez was trying to present her image in the manner of “Bronx girl done good” with other such tracks as “I’m Real” and the “soul-searching” “That’s Not Me.” Lyrics touting, “Even if you were broke, my love don’t cost a thing” serve to prove that J. Lo is no average woman–which is to say a ho who will only fuck a man if money is a by-product.

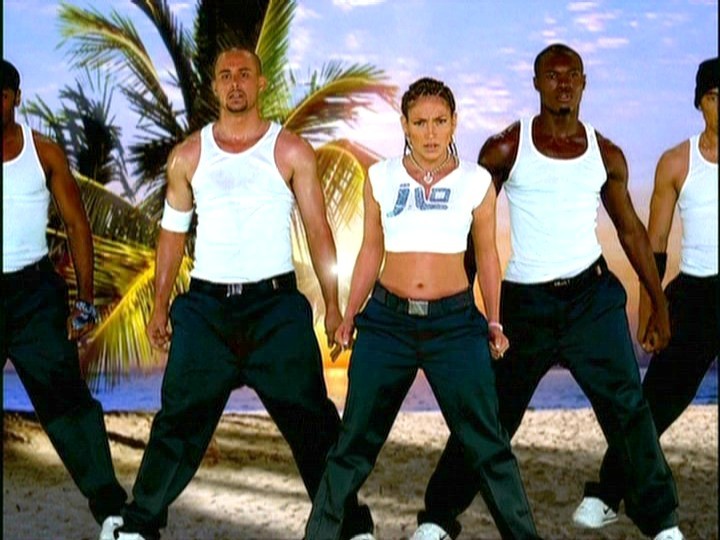

Love was definitely more lo-fi in 2000

Echoing the ironic tone of Madonna’s “Material Girl” video (in which she opts for the guy with the beat up truck in lieu of all the others offering diamonds and “cold hard cash”), J. Lo, too, espouses this notion of preferring a man who understands “credit cards aren’t romance” (though everyone knows that’s not true–credit cards are actually the only thing that equate to the romance you were conditioned to expect from every Julia Roberts, Reese Witherspoon, Sandra Bullock, et. al. movie–except maybe Fear). “What I need from you is not available in stores,” she persists, likely alluding to a decent orgasm (which she’s still clearly been searching for after so many decades of varied boyfriends, finally perhaps settling for Alex Rodriguez because the meat isn’t just in his head).

J. Lo doesn’t seem to think her love don’t cost a thing anymore

Yet now, cut to seventeen-ish years later to J. Lo, still looking exactly the same, but saying something totally different–in sharp and utter contrast to the message she wanted to deliver in “Love Don’t Cost A Thing,” “Dinero” is a neo-capitalist anthem promoting antiquated notions of money being capable of filling the void inside us all. With Lopez bragging, “Me and my man, we stack it up to the ceiling (more money)/Cállate la boca, let me finish (more money)/Every day I’m alive I make a killing (let’s get it)/Yeah, I swear I’ma get it.” So now, not only is Lopez declaring how much she makes, but also how much her current man does–her love, clearly, finally got a price tag and it’s one that warrants telling certain broke asses “you can’t sit with us” if they do attempt to showcase the intensity of their rags (which basically means H&M attire).

J. Lo further demands, “If you ain’t getting no pesos, que estas haciendo?” in sharp opposition to: “All that matter’s is that you treat me right, give me all the things I need that money can’t buy, yeah.” Again, the fact that 2000 was a year far more viable for believing in capitalism further adds to the strange shift in theme Lopez opted for with “Dinero” in 2018, a year that has seen the continued promotion of how being a complete dolt is the best way to assure political and general clout–therefore even more money (because you have to be rich already if you want to pay to play the fame game). Thus, what J. Lo perhaps doesn’t realize is that she’s pushing for an America that further relishes its own stupidity by lusting solely after money and the things it can get you. These things, of course, never including a desire for more education or funneling excess funds into a publishing company that doesn’t churn out bullshit (these days, usually of the fake feminist variety).

“Love Don’t Cost A Thing” might be a sonically inferior song to “Dinero”–and certainly not half as catchy or relatable to the average U.S. citizen–but at least its message was pure. Indicative of some semblance of a human spirit as opposed to a cold-hearted calculating machine behind the eyes and chest where a mind and soul are supposed to be.

Genna Rivieccio is the Editor-in-Chief of a literary quarterly called The Opiate. She has put out two books thus far, She’s Lost Control and You Into It? A Novella About Not Being Into It.