For Marguerite Wibaux, seeing is a matter of intimacy—and intimacy has multiple levels and takes multiple forms. “Seen,” a show up at The Locker Room until May 5 is a show as much about how we perceive one another as it is about how we look past one another or willfully ignore what is before us. The show bears all the marks of a retrospective or a survey: a Parisian, Wibaux is about to return home. All of these works—running the gamut from portraiture to ink drawings to sculpture—were created in the studio she is about to leave behind. It is an exhibit populated by those who most colored her time in New York City. However, what sets it apart from a convenient survey or simple bookmark is the compelling argument Wibaux makes for an artist’s studio practice as an exercise in relational aesthetics.

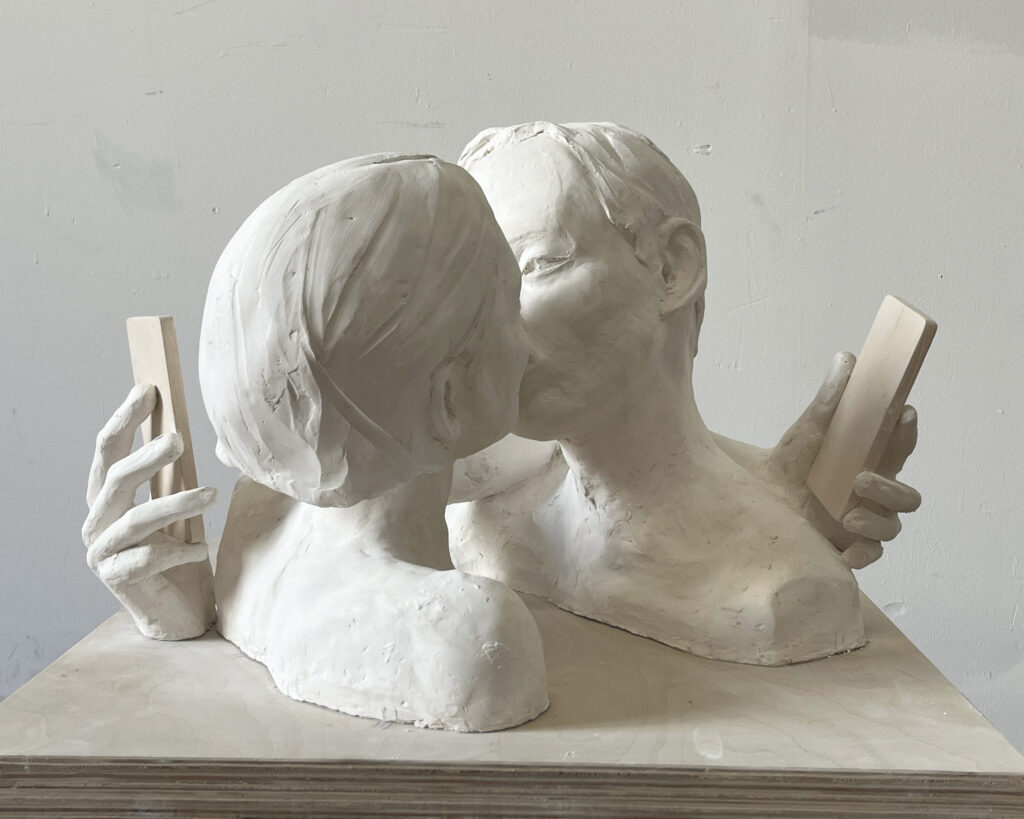

Much as James Rosenquist came to Pop Art after a stint as a billboard painter, Wibaux came to art after a career in advertising. When she left France to live in New York with her family, she threw herself headlong into an omnivorous artistic practice, leaving her former life behind, but taking a particular understanding of desire and reciprocity with her. A telling tension between online life and a literal studio space fuels the show. Messaging runs through every piece: yes, sex sells, but the point of entry to our most intimate moments is usually online. A good many eyes Wibaux depicts are drifting slowly to their phones, no matter how desperately vulnerable a position her work finds them in.

In the most literal sense, the work is in large part observational and documents what Wibaux has seen; in pop psychology, one talks of “feeling seen”; John Berger’s Ways of Seeing dominates so much of critical discourse; and, Wibaux gives us a neat homophone in the idea of a scene. Perhaps that fourth iteration of the syllable strikes the most relevant chord, even though the other three connotations are more readily applicable. The idea of a scene—once the lifeblood of the art world and, in fact, an entire rationale for moving to a city such as New York—is vanishing into the ether online. This show poignantly documents what that process looks like from the vantage point of a soon-to-be-packed-up artist’s studio.

Positing her studio itself as a years-long exercise in relational aesthetics, the artwork stands as the testament to what happened therein. Wibaux writes, “I approach this farewell show as a documentation of my time in New York, through portraiture, sketches, as much as concept- driven sculptures and oil painting as I try, through my practice, to capture the zeitgeist, the joys and struggles of our times.” The show has the playfulness and often the palette of David Hockney, along with a casual and impish yet sensual and voracious eye. Yet, the erotic works, as opposed to the portraiture, feel influenced by Tracey Emin, making use of Chinese ink drawing techniques. An “atelier wall” serves to mix ephemera and reference images in with the finished work. The staging of the show of The Locker Room doubles down on the impression of an artist’s actual space, offering the hodgepodge setting of a home gallery—both another layer of deceptive intimacy and a tongue-in-cheek nod to the nature of the show.

Depicting a studio, of course, predates Velasquez’s little princesses. But a Baroque sensibility permeates the show—indeed, Wibaux grew up partly in Rome where her father was posted as a diplomat. She is drawn, as she puts it, to “high-contrast, dramatic movements of the body, taking sensuality to a sort of transcendental ecstasy.” While her erotic drawings and surreal, sexually charged sculptures certainly reflect that upbringing, her dramatically lit portraits, which naturally favor intense chiaroscuro, are arranged like so many standard cropped tiles on a social media feed. The array, and their ordering, reminds us that there is no more powerful filter than our feelings—or, more specifically, the feelings one who captures or renders an image has toward the person depicted. The desire to be seen suffuses the “The Dinomite Twins” (from Wibaux’s “Horror Vacui” series) in which her models are depicted against a background of hundreds of miniature paintings culled from their social media. The inability to mirror the self on any kind of digital platform is drawn into absurd relief, literally doubled by the depiction of influencer twins who share an instagram account. In another sculpture, a couple passionately kisses while each looking furtively at their phones.

The show reaches its apex in a celebratory orgy and great mingling in a pool. It is perhaps somewhat of an homage to Hockney, who also traversed the Atlantic to find a bright palette and tight bodies. Wibaux executed this work during a fit of the winter blues. She painted her seasonal depression away, conjuring a scene more appealing than a New York City January. It dominates a wall, an admirable feat of changing the emotional temperature in one’s life, not by making a Pinterest board online but by going into the studio and muscling a new reality onto the canvas. Yet, even there, the reality of our digital era menaces and defines the raucous composition. True to life, the party-goers balance phones with their drinks—perhaps interrupting the good time to document it as it happens, perhaps searching for something better somewhere else. In “Seen,” we are shown the artist’s studio as an oasis of pure materiality in a world of smart phones where, on the one hand, everyone comes to call, but, on the other, no one is ever where they are at.

SEEN is on display at The Locker Room (373 South 1st Street, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn 11211) through May 5th. Be sure to stop by and tell them we sent you!

Cara Marsh Sheffler is a New York-based writer, translator, curator, and editor. Her writing has appeared in many publications, including The Guardian; her work has been written up in The New York Times, Cultured, and Libération. As one half of ¡AGITPOP! Press, she collaborates with visual artist Johannah Herr. Their most recent full-length book is a revisitation to the World’s Fair, “I Have Seen the Future: Official Guide.” Sheffler’s writing in it was described by The New York Times as “enthusiastically caustic.”