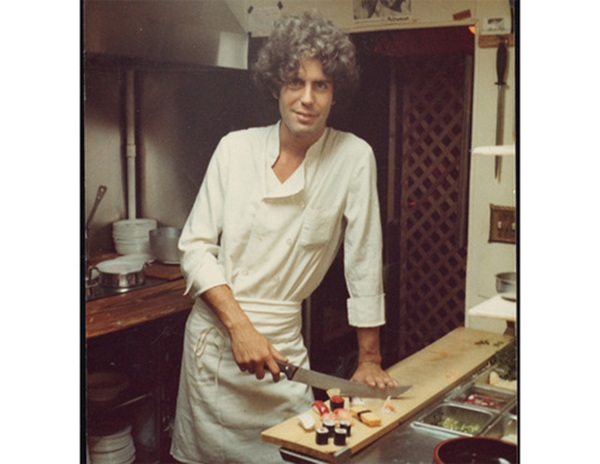

Anthony Bourdain was not a friend of mine. In fact, some of those who know me well thought of him as my bête noir. I thought of him as my bête noir. But I didn’t know the man. I had read his piece, “Don’t Eat Before Reading This”, in the New Yorker in 1999, and it had resonated with me as an amateur food writer and gourmandiser (the last “G” in CBGB & OMFUG is how I learned that word, how I learned most things at the time, randomly, while high). I had left New York almost 15 years before, but we shared the ‘80’s ethos—get high, get really fucked up, and anything can happen. How many people did I know in the ‘70’s and ‘80’s in NYC who claimed to be on their way to becoming famous musicians, filmmakers, authors? No one thought of becoming a famous chef, because that wasn’t a thing that really existed back then. Other than perhaps Wolfgang Puck, the category had yet to be established. But Bourdain changed all that. And then, after driving chefs and the restaurant industry to new heights of prominence, he pledged to never attend the James Beard Awards until the back-of-the-house kitchen worker, mostly Mexicans and other Latinos, were fully represented. He kept that vow, and never stopped raging against the celebrity culture that he had in fact created. This must have brought great pain to him.

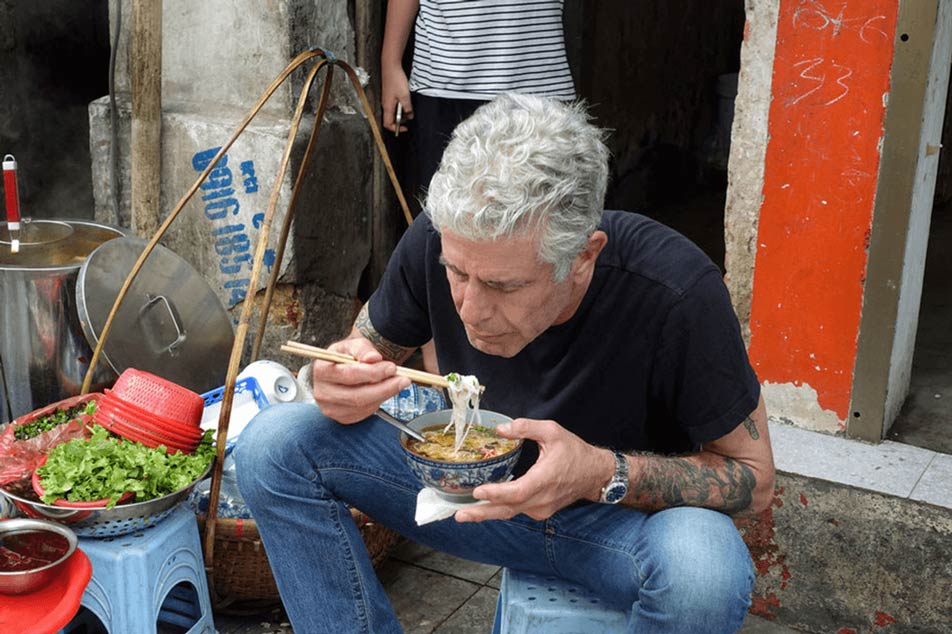

He became what I wanted to be, what so many of us wanted to be in the early 2000’s, a professional food writer. He also became a world traveler, a man fully in charge of his own life. We were about the same age, so I took it as an inspiration to do what I wanted, what so many of us yearn to be, and that is to be free. I wrote and started a blog called Daily Cocaine, which was a rant-filled, bleary-eyed tribute to the taco trucks and Haitian street-food of Miami, but also the strip-club ribs, house trucks, and soul food dives, in neighborhoods to which few writers traveled. Also Jewish delis. I wrote about food and the food industry, which I dubbed the “New Cocaine”, because everybody wanted it, and then wanted more, but I also railed against the food writers of the day, mercilessly ripping them new anuses for their fear of the avant-garde, their obsequious subservience to certain revered, yet mediocre, or worse, chefs and restaurants, their old-timey crankiness, and there, let’s face it, just plain shitty writing. The blog led me to the Miami Herald, the Miami SunPost, Modern Luxury Magazine, and MAP Magazine, where I wrote a column called “The Art of Hunger”. It led me to my novel, and it led me here. But somewhere along the way, I lost my taste for Bourdain, whether through resentment, my competitive nature, or his sheer ubiquity. I had had enough of his sanctimonious pronouncements (I always referred to him as Saint Anthony) that everyone in the world lapped up like a toy Pomeranian, and now I only wanted the world to hear MY voice. Looking back, I realize I may have made a mistake. He was always one of the good guys, but maybe his shtick, in the end, for me, just got stale. I can’t be sure.

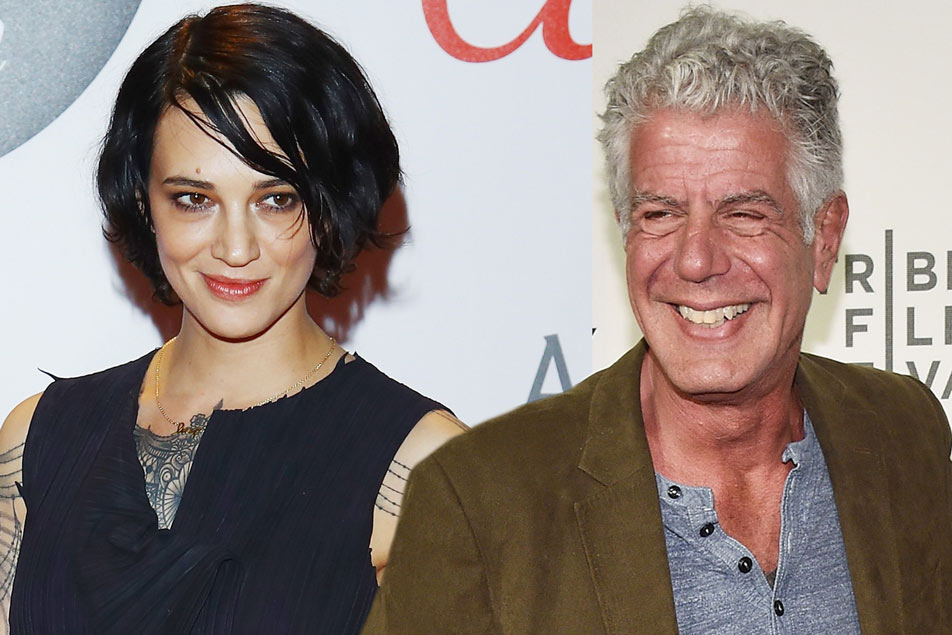

So many things have changed in the world of restaurants and food writing, but so much has not changed. Restaurant work is brutal, and Bourdain reveled in it. But for those who do it every day, the romance with which he described it, has perhaps not aged well. And in my one encounter with Bourdain, at the South Beach Food and Wine Festival in 2008, I asked him, in my mordant and somewhat acerbic fashion, “With all the emphasis placed on seasonal, and especially local ingredients, how would you incorporate Miami’s most well-known ingredient, cocaine, into your repertoire?” He was not amused. “What do you think, this is the eighties?” he bellowed, Michael Ruhlman egging him on. He then trudged off the stage early, I guess my question had rattled him, as most in the audience were middle-aged ladies from the midwest there to see a celebrity. I had wanted to connect, but he took it personally, as though it were an attack, which, in the end, it probably was. He was no longer a daredevil to me, but an old actor playing a part, hanging out behind the set, having a smoke with the extras. All these mixed feelings I had about him, did he perhaps have the same doubts about himself as well?

Of course, he would go on to even greater fame, and his personal life seemed idyllic as well. We can’t know what drove him to such despair that he took his own life, but the wounds and scars that drugs and the high life cover up, sometimes never properly heal, they just sit there, unattended, waiting to rupture. Fame and success can have the same effect, something most of us will never know, or perhaps, understand. In any event, I salute the man who greatly influenced not just the way I write, but that I write at all. I hope you find peace, Saint Anthony.

Danny Brody is the author of The Cold Shake (2018), a noir novel of ‘70’s New York, and The Gilded Palace of Sin (2008), a collection of poems. He created the seminal Miami food blog, Daily Cocaine, penned numerous food, wine, and booze columns for the Miami Herald, and wrote The Art of Hunger column for MAP Magazine. He has also written art, design, and architecture pieces for Modern Luxury Magazine, Design District Magazine, Social Affairs, and Art New Orleans. He lives in the South Bronx.