“McSorley sold his ale across the bar at two mugs for a quarter. A tired man could go in, buy his mug, sit down and rest until his weariness passed. It was a meeting-place for artists, writers and musicians of the quieter kind. It was quiet there, and blue clouds of smoke from pipes and cigars were rarely disturbed. Conversation was quiet, earnest and reminiscent. There was about the place that made one feel reasonable and comfortable.” — The New York Times, January 11th, 1937

East Village, New York— Before famed American writer Joseph Mitchell, published The Old House At Home in The New Yorker magazine in April of 1940, McSorley’s Old Ale House was already legendary in its 86 years. Descriptions of its unique qualities had graced the pages of the New York Times, Harper’s Weekly, and The New York Herald

Mitchell found his way to McSorley’s “ground floor of a red brick tenement” at 15 East 7th Street well after poet E.E. Cummings advocated ‘drinking the ale that never lets you grow old’. (Penned in 1923 during Prohibition.) Mitchell would stop in every now and again much later in his life to tell the bar’s owner, Matty Maher, otherwise. “He was a contrary old fella, he was,” said Matty of Mitchell. “He liked saying that he was responsible for our success —as if the ale and the history of the place had nothing to do with it.” And it’s the bar’s continuous history — recorded in painting, song, and prose by numerous artists, writers, and musicians— that casts McSorley’s in a different light, far apart from all other drinking establishments. It’s why for generations of New Yorkers and out-of-towners alike the resonance of the bar’s story remains an important one: Once famous and iconic landmarks of New York, places that were absolutely synonymous with the city, Penn Station, the Biltmore Hotel, Sweet’s, Luchow’s and Sammy’s Bowery Follies, are all gone. But McSorley’s, against all odds, lives on unscathed.

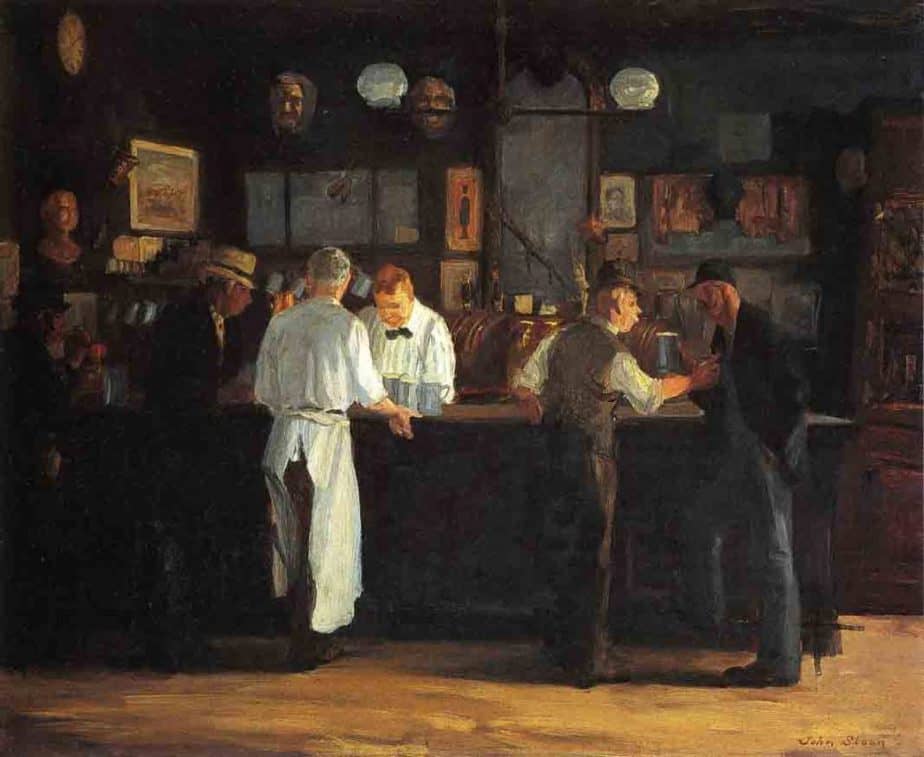

John Sloan, McSorley’s Saturday Night

New York’s Lower East Side, 1898

Reginald Marsh, (Student of John Sloan) McSorley’s

“The one who got it right was the artist, John Sloan (1871–1951),” said Matty, referring the American Ashcan painter who, with his colleagues in the early years of the 20th century, sought to capture life in New York City as it really was, warts and all. And by “getting it right”, Matty was speaking of Sloan’s ability to capture in paint “the humble humanity of hard-working people and the magical spirit and energy” of what arguably is the world’s most famous bar and one he’s been steadfastly standing guard over for fifty-five years.

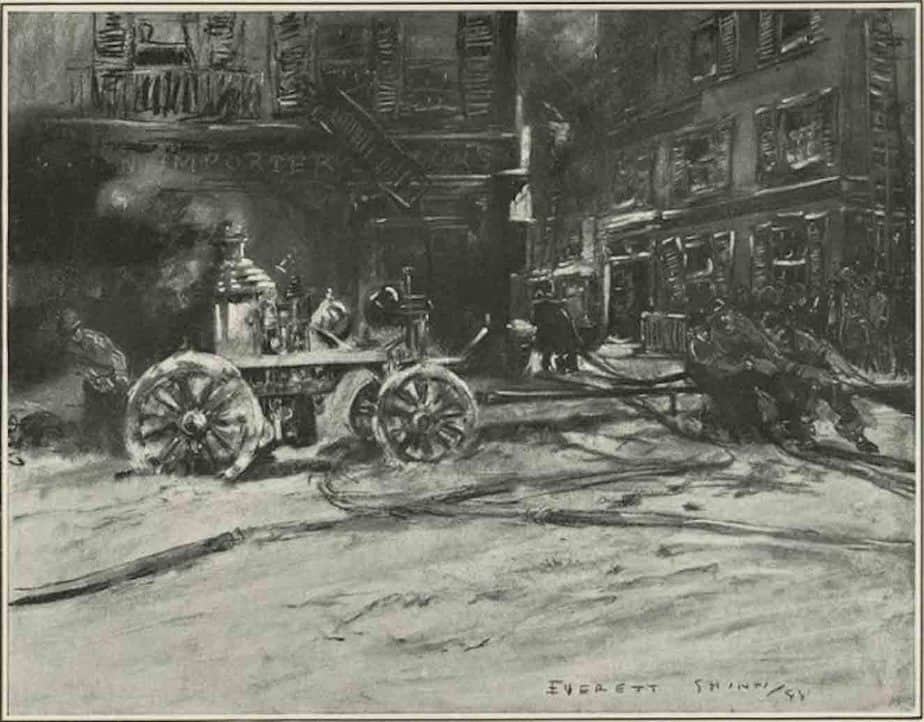

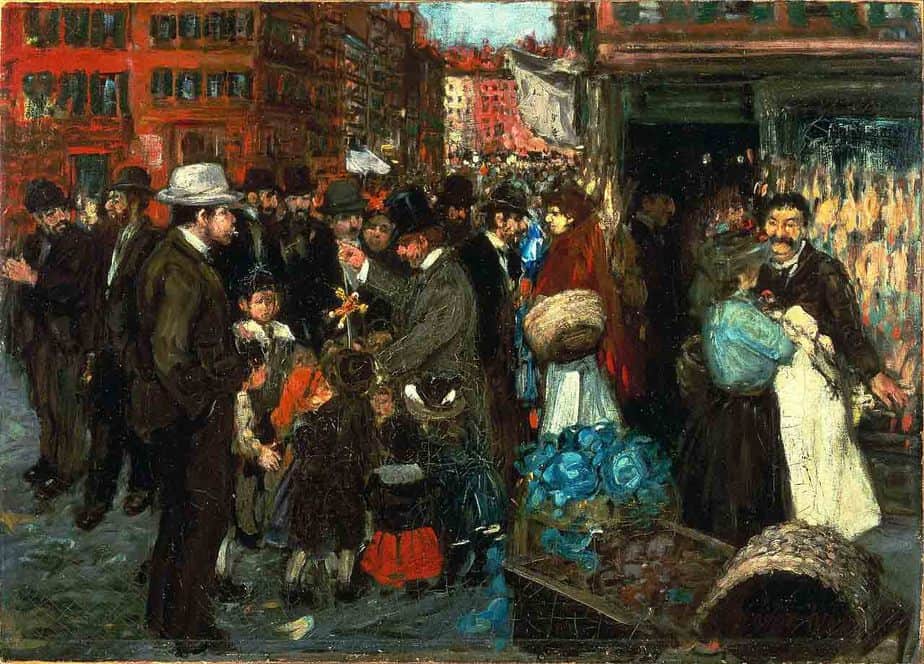

Sloan’s fellow painters —and McSorley patrons all— Robert Henri (1865–1929), George Luks (1867–1933), Everett Shinn (1876–1953), William Glackens (1870–1938), and George Bellows (1882-1925), formed their group as protest to and rebellion against Academic Realism and the American Impressionist movement. Popular artists of the day, John Singer Sargent, and William Merrit Chase, two of the wealthiest and most sought-after portraitists of the times, were part of the old guard and their work irritated these urban realistic painters. The Ashcan School preferred darker tones over lighter ones, crafted works heavy with impasto, painting subjects more prone to getting sullied from ash than having their portraits wrapped in gold-leaf —no Gilded Age pomp lingering here. In fact, their inspiration stems not from an elitist, idealistic view of the world, but springs from the everyday activities and unglamorous lives of ordinary city dwellers; the working man struggling to make ends meet. The over-worked and underpaid women and children laborers stuck in heatless factories for long days. Theirs was a world of the downtrodden living in slums and overcrowded tenements. A world replete with hucksters and swindlers, firemen and policemen, boxers and barmen, vaudeville dancers and prostitutes who lived, worked, and died on streets named Hester, Essex, Bowery, Eldridge and Canal. George Luks, the heavy-drinking, barroom brawler of the group once said: “A child of the slums will make a better painting than a drawing-room lady gone over by a beauty shop. Down there, people are what they are.”

Robert Henri, Snow In New York, 1902, National Gallery, Washington DC

According the late art critic, Robert Hughs, the spiritual leader of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri, “wanted art to be akin to journalism… he wanted paint to be as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter.“

The bustle of Mulberry Street, c.1900

The notorious Sammy’s Bowery Follies, photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt 1934

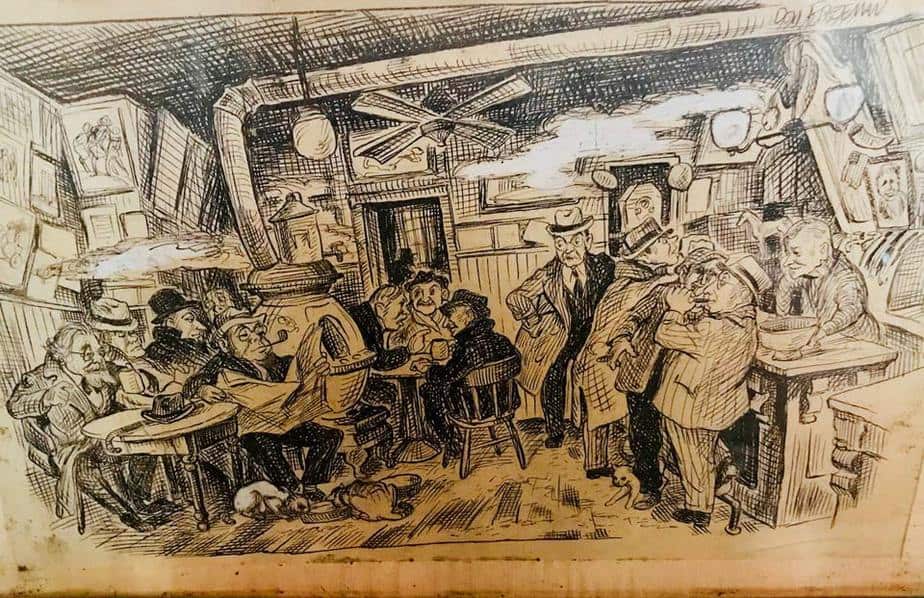

Cartoonist Don Freeman capturing McSorley’s during Prohibition. Note the single door to the backroom which, after Prohibition, would become illegal. Widened in 1934 to appease new State Liquor Authority guidelines.

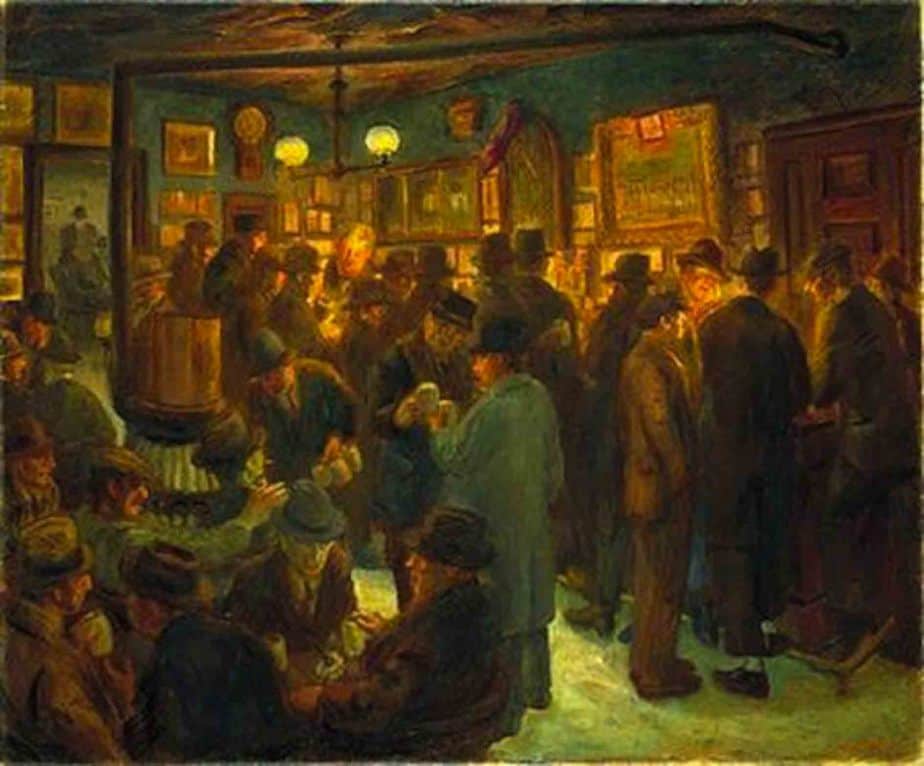

George Luks, McSorley’s Old Ale House, c.1910

In 1912, Sloan painted McSorley’s Bar. In 1913, he exhibited the painting at the infamous Armory Show held at, of all places, the headquarters for the 69th Infantry Regiment (aka The Fighting Irish) on Lexington Avenue and 25th Street (In the second-half of the 19th century, The Fighting Sixty-Ninth were headquartered right across the street from McSorley’s in the Tompkins Market).

McSorley’s Bar was eventually purchased by the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1932, the first work by the artist to enter a public collection. In a letter to the Detroit Institute of Arts, John Sloan proclaimed: “Had all saloons been conducted with the dignity and decorum of McSorley’s, Prohibition could never have been brought about.” Matty Maher is pleased to point out that the bar’s motto is still Be Good Or Be Gone, and, he says: “Today’s hard-working men and women need a ‘reasonable and comfortable’ place like McSorley’s more than ever.” He’s also pleased to inform that on Sunday, February 18th, The Old House At Home, as McSorley’s was affectionately called in the 19th century, will be celebrating the bar’s 164th Anniversary. ‘All are invited.’

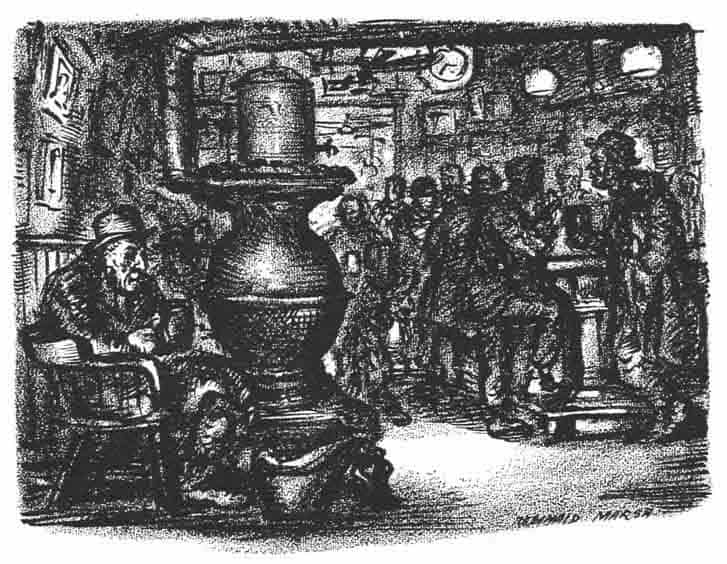

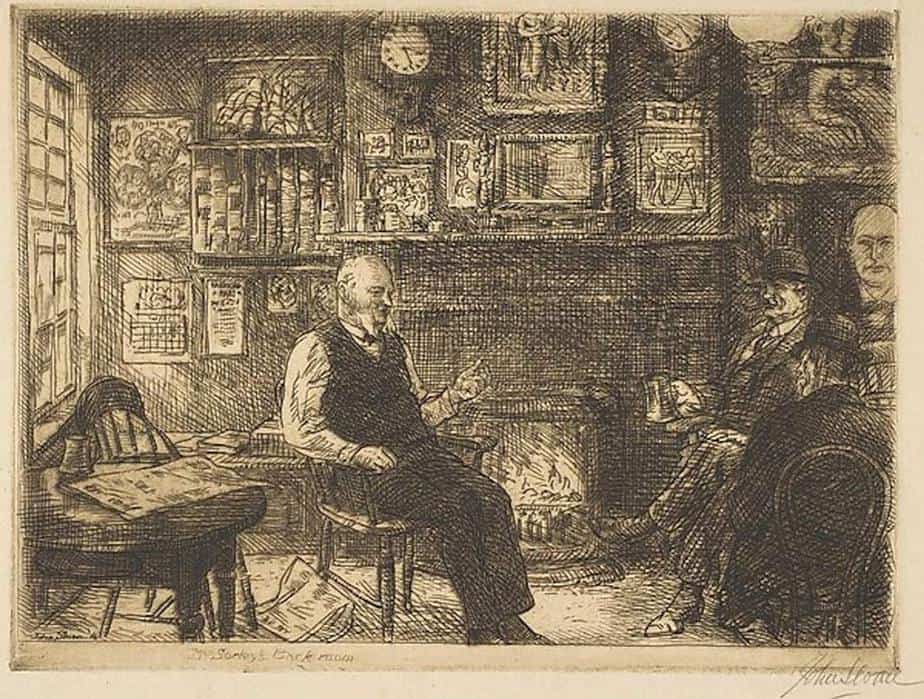

John Sloan, Etching of the Back Room, 1910

John Sloan, McSorley’s Cats, 1929

Berenice Abbot November 1, 1937

American Impressionist Childe Hassam’s 1891 depiction of McSorley’s

Louis Bouche (1896-1969) McSorley’s 1940

In 1943, Woody Guthrie sings to the working man inside McSorley’s.

Everett Shinn, Street Scene at a Fire, 1899

George Bellows, Boxing Scene

Everett Shinn, Vaudeville Theater Scene

George Luks, Street Scene (Hester Street)

John Sloan, McSorley’s Back Room, 1910

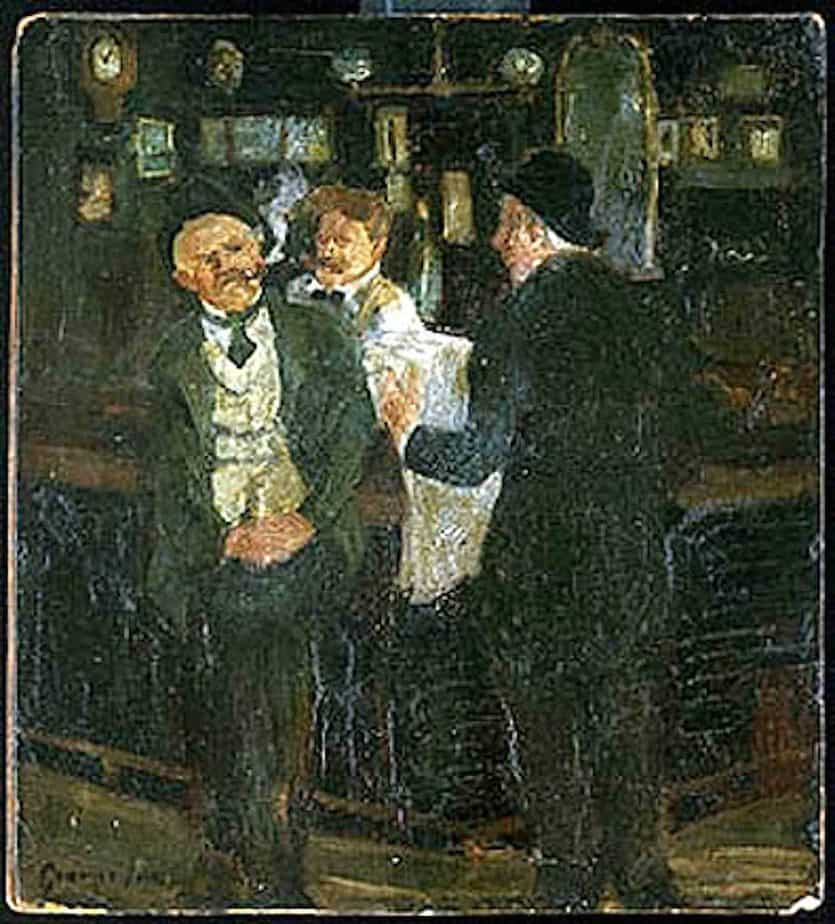

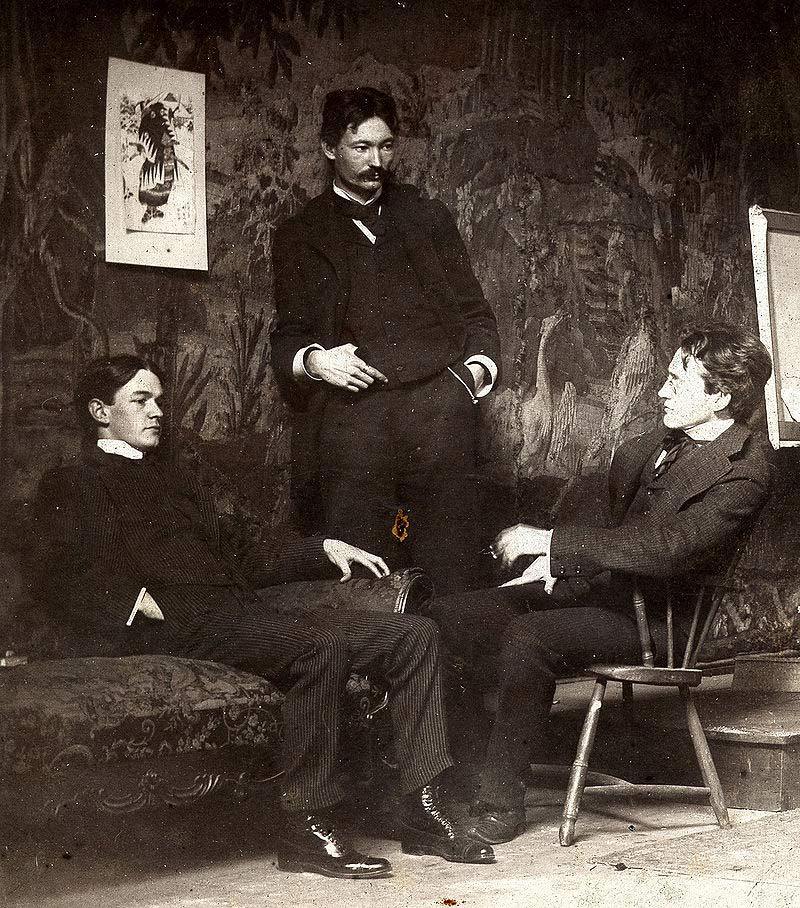

Everett Shinn, Robert Henri & Joan Sloan

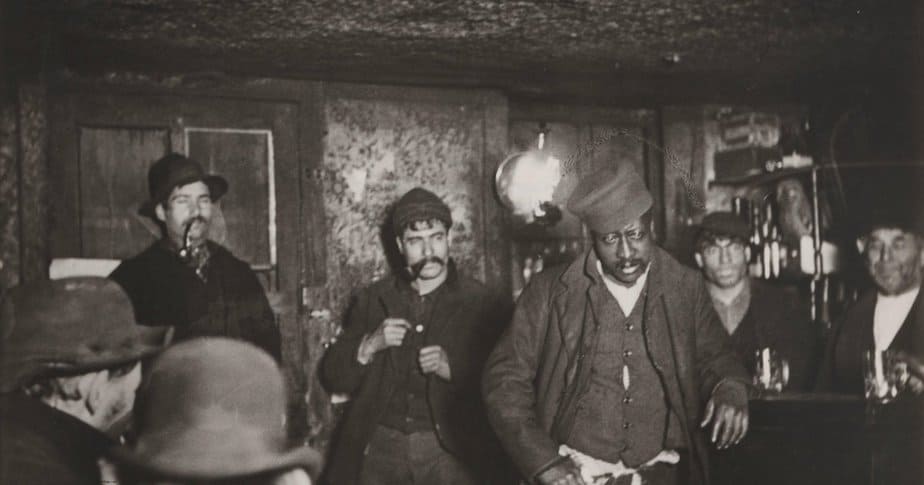

Jacob Riis, A downtown Morgue (unlicensed saloon), c.1890

John & Bill McSorley, 1903

Native New Yorker. Artist. Publisher. Curator. Writer. Loves jumping into other people’s dreams.