It’s not surprising that the San Francisco-based artist Klea McKenna’s earliest memory is filled, not only with various visceral, almost tactile sensory messages from the past, but with humor and drama as well. More so than this, it involves each of her parents, who, depending on the reader, may also occupy a certain chamber in their hearts and minds.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

“There is a window,” says a reflective McKenna over the phone, in a more ‘to the point’ cadence than some might expect. “In the summertime the window would be open. I was kneeling on our couch looking out. I remember the feeling of burgundy velour, the heat and the feeling of the screen. I had a very large head and I was pushing it against the screen, trying to see something. I remember a cat. We had a lot of cats. And then, just like that, I fell out of the second-story window.”

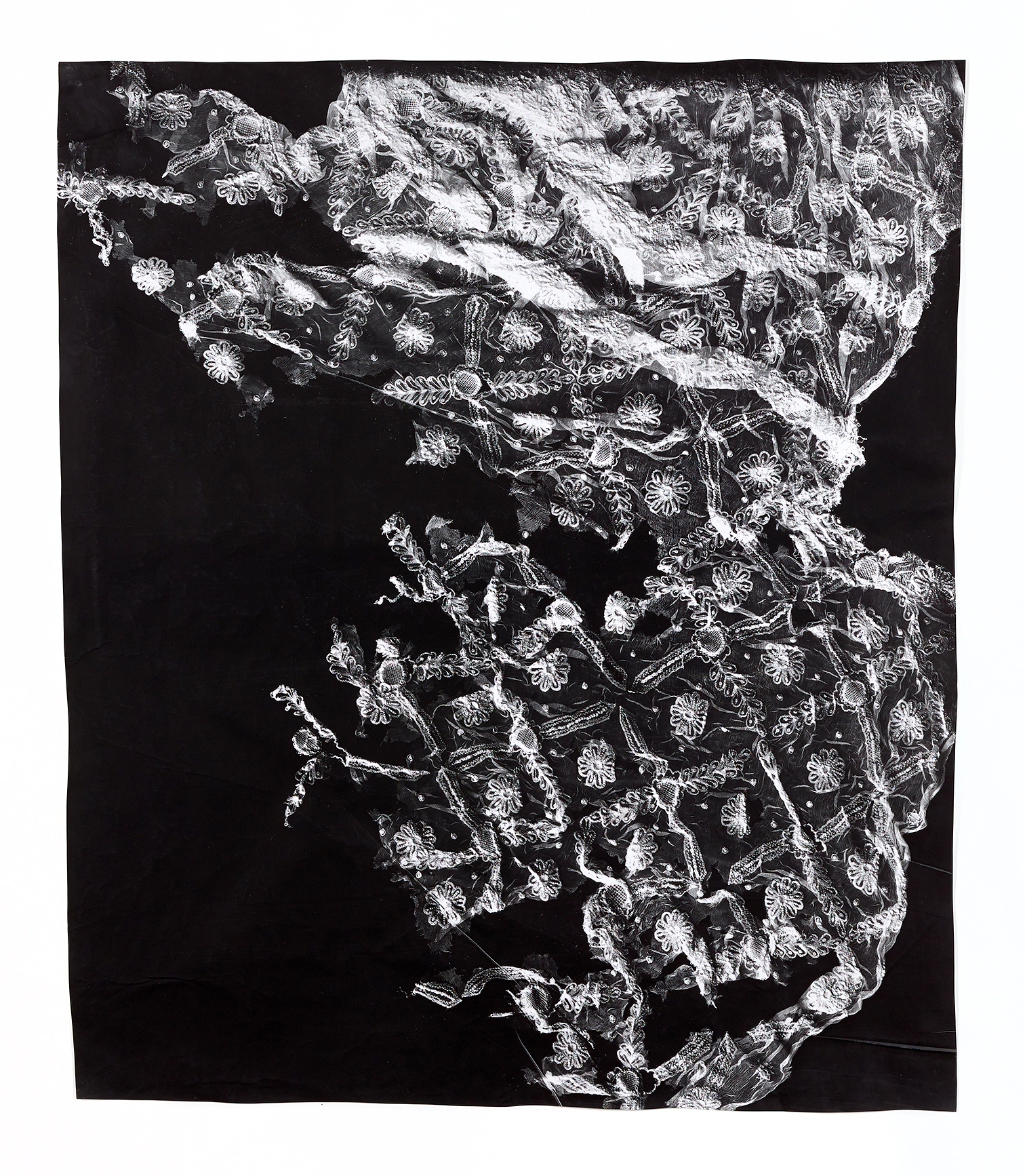

“Manton de Manila,” Unique photographic relief. Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Impression of a hand embroidered silk Manton de Manila or Piano Shawl. Spain. 1930s .42.5 x 73.5 inches, 2018. Photo courtesy of the artist.

There’s all sorts of tells for how McKenna (born 1980) might have been hardwired from birth to break through certain confining membranes-windows, boxes, expectations, dimensions-but perhaps due to this early, inevitable blunt impact with the hard earth of Occidental in Sonoma County, California, McKenna seems extraordinarily grounded.

“My dad was standing there when it happened,” she says. “The way our house was situated you had to run down the stairway, down the driveway, and around the house. It’s a long distance to get there.” Readers can now imagine a terrified, hyperventilating, lithe-limbed Terrence McKenna frantically whirling around the home he occupied for the first ten years of Klea’s life, before he and Klea’s mom, Kathleen Harrison, also a celebrated ethnobotanist, separated. “My mom was in the bathroom and stepped out just in time to see just my feet go over the edge,” Klea recalls. “She just froze until she heard Terrence shouting, ‘She’s alive! She’s alive!’ ”

And very much alive, still in 2018, or at least as much as a singular artist truly hitting their stride could or should feel. McKenna is in the midst of unveiling bicoastal solo exhibitions, both titled, Generation, the first, at Von Lintel Gallery in Los Angeles (her third solo with the gallery), the other at Gitterman Gallery in New York City (her first solo in NY), opening September 12th.

Klea McKenna in her studio. This and featured image shot by Airyka Rockefeller.

Both shows feature McKenna’s latest series, mostly complex black and white, silver gelatin photograms of textiles, created, mended, mutated and deconstructed over the last two centuries by innumerable hands and layered over light-sensitive paper, creating entirely unique H.R. Giger meets Anna Atkins reliefs that are in many ways alien to both the untrained human eye and the discerning, critical gaze of seasoned photographers alike.

The works are, as the title of both shows might suggest, a testament to legacy, and though Klea’s last name certainly evokes her late but increasingly ubiquitous father-famous among seekers, philosophers and self-professed psychonauts the world over-they are a greater celebration of female labor, not just through the formation of textiles, clothing, quilts and other fiber art, but to the act of creation itself. “The idea that spurred me on was the labor it takes to make them, these mostly handmade things, made mostly by women as far as I can tell,” she says. “It’s not just about the labor, but the way things wear down.”

In McKenna’s previous series, Web Studies or more recently, Automatic Earth, which was featured heavily in her previous solo show at Von Lintel (some selections can be seen at Gitterman) the artist employed a similar rubbing or relief technique to reproduce and record the rings of various old, Northern California Cypress trees that had been cut down sometime around WW2. These were a literal expression of how an object records time-each year, one ring-as we know from grade school. “You can tell how old it is. You can see in those marks, those rings-the droughts, the floods-the flaws and imperfections tell the story. The tree wants its rings to be perfect concentric circles.”

“Ouroboros (2),” Photographic Relief, Unique Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Sepia and selenium toned. Impression of a salvaged fringe of a silk piano shawl or Manton de Manila. Spain. 1890s. 49.75 x 40.5 inches 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Klea would have you know the clothing is less literal or direct, as each stitch and mark is made by someone’s hand and recorded like a text. Each spot that’s worn-through or repaired or mended is altered throughout generations and with real intention. Great-grandchildren may add embroidery or sequins over time-a new, fresh chapter to the ongoing chronicle and yet destined to degrade. “You can actually read its story through the texture,” adds McKenna. “The first two I did were fabrics or textiles I found in my mom’s house, which is a bit of a ‘bohemian hoarder museum.’ You could find the entire history of the 1960s in her house.”

Objectively speaking, quality art is an earnest, sensitive and yet bold investigation of one’s surroundings, personal experience, family, community, culture, country, planet and universe (micro/macro). Klea’s photograms are all these things and more. It’s a unique phenomenon-your parents, your father, his legacy especially-not entirely belonging to you, or even to him it would seem. This latest series, though very “hands on,” is also manipulating light and the complicated nature of perspective while utilizing a highly individuated, experimental and thoroughly thought out process for exploring the shadow dimension of our universe and the objects and humans and energies that inhabit it, our at once valiant and highly fallible elders by no means excluded.

“The idealism of my parents’ generation, washed over from the ‘60s, in my eyes, extended into about the mid ‘80s,” says McKenna, as much fascinated by generation as its antithesis, degeneration. “A lot of my friends grew up on communes, the whole scene in Northern California is a lot like that. It carried them a certain distance, to a certain point and then it all started to fall apart.”

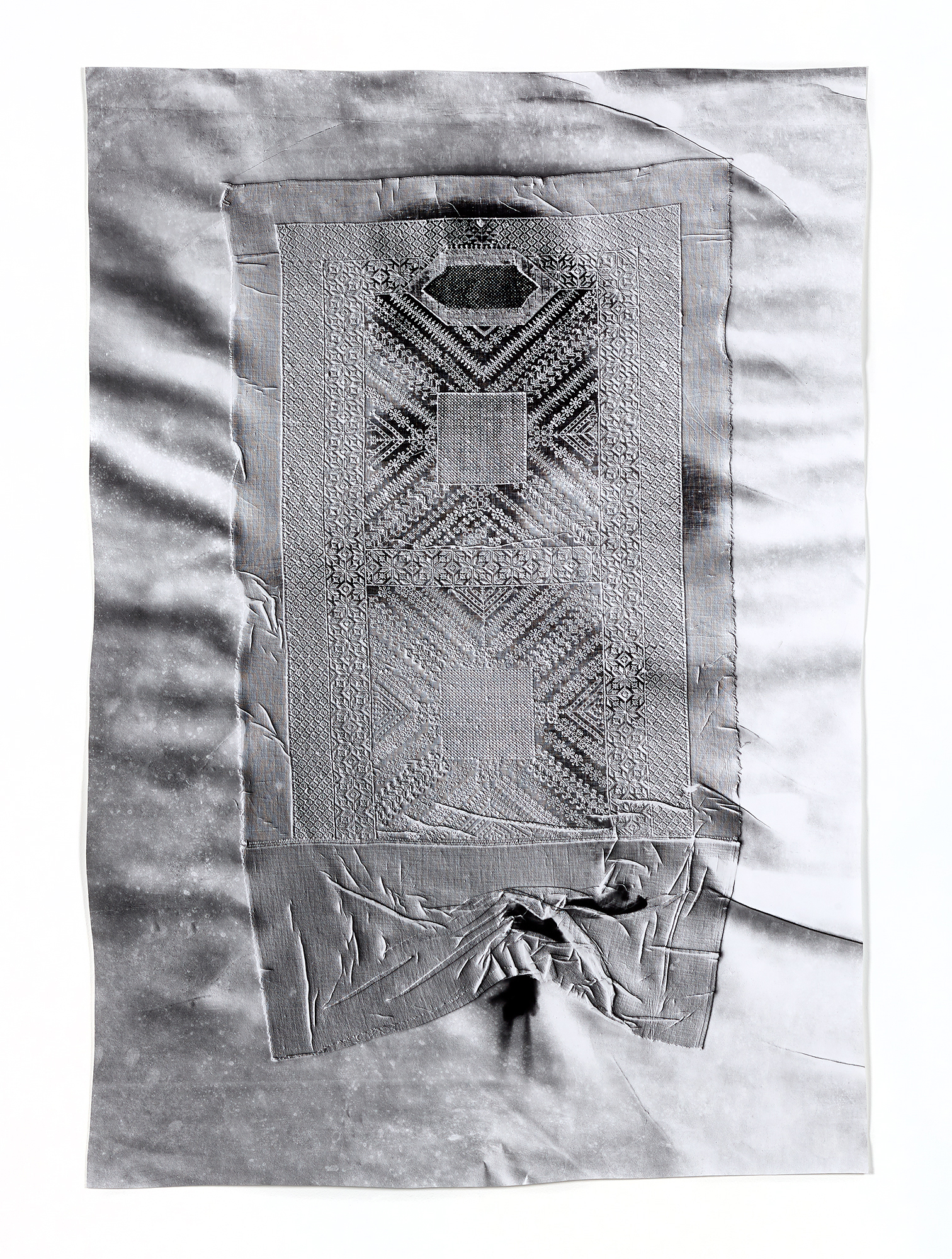

“Growing Field (2),” Unique photographic relief. Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Impression of a hand embroidered decorative horse blanket made for a wedding celebration. Uzbekistan. Circa 1920s -1940s. Image courtesy of the artist.

Though Klea is certainly in conversation with the high-water-mark dream of the Haight-Ashbury days, her intricate work is conspicuously, almost violently devoid of color. Certainly absent is the trippy, cliché, psychedelic imagery. More absent is the base material itself, quite refreshingly (something new), it’s fiber art without the fiber. Though rife with history, a human touch and light, Generation screams of anti-matter.

“It gets a little dark,” she says. “There’s the natural rise and fall of idealism in one age group, compounded with the cultural shift that happened in the ‘80s: the Reagan administration and the economic shift that happened in the black market. Those alternative lifestyles were fronted by money that came from drugs, whether growing, selling or trafficking them. The war on drugs takes a toll on that.”

So much of Generation (both shows) seems to explore, or ask of us, “What has value?” It’s a good question; maybe the most vital question of the new millennium. Any guesses? The Trump brand? A glistening faux derrière? A healthy Instagram followship? Tesla’s stock? New Nikes? A Jeff Koons piece? What has value to Americans right now? Life itself seems to be the best or only answer. But within the frame of 1stworld, past-modern life, say 80 summers and 80 winters for the median Homo sapien, what has true meaning or value? For McKenna, now a young mother of a three-year old daughter, imparting a value system is no easy task, especially when your own childhood reference point is one of “counter-culture” societal disentanglement.

“Snakes in the Garden,” (1) Photographic Relief. Unique Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Impression of a salvaged fringe of a silk piano shawl or Manton de Manila. Spain. 1890s. 40 x 36 inches, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

When not falling out of windows at her home in Occidental, where her mother still lives, Klea remembers spending time on “Big Island” in Hawaii with her father in a very small, one-room house, which meant no electricity, an outhouse in the woods, and one rotary phone a mile away which was shared by the like-minded community.

“Extremism isn’t that sustainable as far as parenting goes,” says McKenna, taking a moment to note that her husband of seven years had a more traditional upbringing. “It’s one thing to situate your family in a situation where certain things aren’t available in their daily lives. It’s another thing to situate your family in a situation where those things are available, but deny them those things.”

Though Klea often delves into what she calls the “shadow factors” of her parents’ lifestyle during her early life, which in many ways helped dissolve a natural hierarchy of authority, especially after her parents’ divorce, she’s careful not to dismiss their greater positive imprinting. “I think the perspective they gave me on our relationship to nature is something I’ve really held onto,” she says. “They both had this anthropological perspective, being ethnobotanists. They really pressed upon us (Klea has an older brother, Finn) the idea that everything is alive. This idea came largely from indigenous world-views; this animism within everything. This is totally common in a lot of cultures, but not in ours. If I stepped on something, or even slammed my bedroom door, I had to apologize to the door.”

“Your Eyes Aren’t Eyes. They’re Bees, (1)” Unique photographic relief. Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Impression of a hand embroidered burqa face veil. Afghanistan. Circa 1970s. 41.25 x 28.75 inches, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist

This can be seen and felt in Klea’s artwork. She’s trying to give some agency to the materials and the subjects themselves. More than just an artist perhaps, she is a facilitator of an interaction between these things. What things exactly? That’s for the viewer to discover. Look deeply. Try it. It doesn’t hurt that badly. Her work, as she sees it, though aesthetically gorgeous, sensual and mysterious, is dependent on the idea that these things, the sinewy, ghostly photograms-a physical and yet metaphysical expression of these textiles-have something to say for themselves. “They’re not just dead matter.”

McKenna is talking about what some could perceive as seemingly inanimate fabric, but she could be unintentionally talking about most artwork out there currently…Dead matter.

It wasn’t an easy journey to arrive at a process or medium that can produce such special objects. Klea first experimented with photography at 12. Her mother’s friend would let young Klea come by after school and develop film in her basement, a makeshift photo lab. Here are more sensory memories-the smell, the quiet; the darkness. Her mother and Finn liked drawing. They still do. Terrence had a way with ideas and words, though they never immediately connected with his only daughter, as opposed to Finn, who took to his worldview. Photography could be her thing.

Klea dropped out of a “terrible, terrible high school” at 16. She started taking photography classes at a local junior college while working in a grocery store and later a clothing store. She danced in various local companies until she was about 21, but hips don’t lie. She soon found her way into California State Summer School for the Arts, which was held at CalArts. “It was amazing and free for low income kids,” she remembers. “I lived in the dorms with kids from all over the state. It was mind-blowingly great. Three years in a row-age 15, 16, and 17. Two years for dance, one year for photography. This is when I realized there was such a thing as an ‘art world’ and when I learned that going to college could be the way out of this life.”

She also had a fantasy of moving to Italy. “I was really into Renaissance Art,” she says. She saved enough money to enroll in an international art school program, which brought her to Florence for six months. “I traveled quite a bit between 1997-98, and in the meantime, finished requirements for my GED. I came back and went to UCLA. I presented a portfolio, mostly photography, and got in somehow. It was during my first year there that my dad got diagnosed with brain cancer.”

“La China Poblana (1),” Photographic Relief. Unique Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Sepia toned. Impression of a handmade skirt, heavily sequined with an eagle and snake emblem. Mexico. Made 1920s, altered in 1940’s. 40 x 78 inches, 2018

At this point, Terrence had been living in Hawaii permanently. Klea was traveling abroad once more when she got a call that her father collapsed suddenly and was in a coma. He was soon diagnosed with Glioblastoma Multiforme. Twenty years ago especially, this was considered a death sentence. “I don’t think I had spoken to my mom in a month and dad in maybe two or three months,” she says. “I was just out of touch. We were living our lives. My brother was in New York and just said, ‘Get here right now.’ We have an understanding that I show up for the hard stuff.”

Klea’s father lived for roughly a year after diagnosis. She doesn’t remember much from that period. “He did treatment in Honolulu, then at UCSF, then died here in California,” she says. “He went through a lot of different stages: fight at all costs, accepting it and reflecting on his life. It was a process for everyone. My brother and I came in closer for that period.”

And for a man who, let’s say, saw some things, did he share his hypothesis for an afterlife? “He was thinking about it in his typical, intellectual, big-picture, philosophical way,” she recalls. “Also, he was much more emotionally available. Tender even. Not really his thing in general. He would talk about dreams and visions in his last few months or weeks, things about his grandparents and his childhood, like the idea of one’s genetic code, the moment you die, shooting both forward and backward into your ancestry, into the past and the future.”

Klea McKenna in her studio. Photo by Airyka Rockefeller.

Klea cites Immortality, the 1998 novel by Milan Kundera as a memorable guide to help her through the loss of her father and a worthy tool to help contextualize his life and legacy.“It’s about looking at ourselves as life authors-writing our lives the way one writes a book; a way of creating a legacy while you’re living it.”

Terrence would often write about himself in this manner and frequently in the third person. He did this on the backs of images he took while catching and collecting butterflies around the globe for roughly four years starting in the late ‘60s, which Klea beautifully packaged and chronicled in “The Butterfly Hunter.” There was a short period, right before her parents divorced, where Terrence taught Klea how to unpack and handle the butterflies, a strange, prescient and unusually intimate moment. The book was published eight years after her father’s death. Klea discovered, along with the 2000 butterfly samples in an inherited trunk, safe from a fire that destroyed much of his belongings, that her father, a nerdy beat poet of sorts, was delightfully fictionalizing his own existence.

“For example,” Klea begins, “A photo might read: ‘Japan, Tokyo, summer 1970, HCE at the age of 23, 11 months of exile, and feature the lyrics to a Bob Dylan song. ‘An’ though the rules of the road have been lodged/It’s only people’s games that you got to dodge/And it’s alright, Ma, I can make it.’ (‘It’s Alright Ma [I’m only bleeding]’).”

With “The Butterfly Hunter,” Klea was remembering him on her own terms and in her own way. However, the book in many ways exists outside of her artistic oeuvre. Nevertheless, it was a crucial step, or more like an essential hinge in her unique creative narrative.

“Unpacking those butterflies was a very weird, touching experience-the formaldehyde, the headaches, these fragile little bodies turning to dust almost,” she says. “The process was a ritualistic exercise in mourning. I shot them in natural light between 10am and noon everyday. I would unwrap these tiny little envelopes. We were communicating across time. There was a thread between us. I was untying a knot someone else had tied.”

“Standing in Velvet Water (1),” Photographic Relief. Unique Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Impression of a fragment of a sequined, silk dupatta. India. 1930s. 42 x 36 inches, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

The book came out roughly halfway through Klea’s MFA program at California College of the Arts. By this point, she was dealing mostly with a long-term documentary project, focused on an indigenous family in Mexico, an extension of her mother’s anthropological work. She was also consciously rejecting the hyper realistic, documentary style or “street-photography” aesthetic, which was popular in the mid to late 2000s. “I was steeped in that world and I was increasingly becoming frustrated with it,” she says. “I wanted it to feel like there was a real alchemy. Right around the time of the book, I started to feel disenchanted with my own process. I was finding ways to lose control.”

Alchemy. Losing control. Her father’s daughter after all? Klea found herself building out analogue cameras, which she would stuff with rocks, water and other weird items in a move towards a more performative process. She was “chasing experiments” as she says. This led to ditching the camera entirely. Enter the photograms, a direct light to paper image, non-reproducible, no negative, just an object placed on the paper either depicting a shadow of an object or a very crisp image of an object directly on an image.

Anna Atkins, considered by many to be the first female photographer, utilized the photogram, cyanotypes especially (early blueprints really), as a means to document various species of seaweed and create a larger classification of plants. “Anna was the first woman to use it and the first person to publish a book with photographic images in it,” notes Klea. This method was the best scientific alternative at the time, as opposed to drawing the plants, which, somewhat ironically, Klea’s mother, Kathleen does frequently to this day. She even hosts plant-drawing classes in Occidental.

The artist Man Ray’s shadows on paper, or “Rayographs,” a term he coined in the early 1920s, were simplistic, silhouettes of everyday objects often captured in silver gelatin prints. These really brought the photogram process and general medium into the larger modern art cannon.

“What does it mean, all these companies discontinuing their analogue technology?” asks McKenna. “There are so many other things they [analogue photography hardware] can do that they haven’t been used for. That’s my job, ‘How else can we record reality?’ This is such a regenerative question for me.”

“Kingdoms Are Clay (1),” Photographic Relief. Unique Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Sepia and selenium toned. Impression of an assuit shawl made of linen and silver. Egypt. 1920s. 42 x 32 inches, 2018. Image courtesy the artist.

Klea’s husband often jokes that her particular skill is coming up with the most inconvenient way of doing something. These works are highly impractical, involving no ambient light. Nature in pitch black is her darkroom. Emphasis must be placed on the texture-based quality of this latest series, made by embossing the photo paper in total darkness into the surface of textures, then exposing light selectively to it, where the light grazes across the paper like an air brush (flashlights, torches are used at various angles), the image made by the raised texture, much like a blind letter press. The process, often involving large sheets of wet paper and peeled off, in some capacities, is closer to printmaking.

As for the textiles, they come from all over the world. “Once I figured out what I was interested in, I started hunting for them,” says McKenna of her fabrics, understanding better than most the nature of cultural appropriation. “Thrift stores, EBay, the cottage industry, flea markets. I couldn’t ignore the history of the thing. I had to respect that.” This involved a lot of research. Each work then becomes a visual story of history-a tactile expression of the reverberation of DNA across the planet, across generations. “Themes kept reoccurring, like the migration of objects and trends between cultures. What we perceive as quintessentially Mexican might actually be from India, or quintessentially Spanish actually from China. For me, I hope they have their own kind of power visually.”

“Sweeter than Salt,” Photographic Relief. Unique Photogram on gelatin silver fiber paper. Impression of every piece of a woman’s traditional tunic from Swat Valley. Pakistan. 1950s Diptych, 72 x 84 inches, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Generation, Klea would like to remind you, quite literally means to make something, or create something. Or closer to her own story perhaps: to be born of something. “All of this comes down to, when focusing in on the minutia of the world, that I’m embracing imperfections,” she says. And what about the things we can’t see, something more spiritual, inter-dimensional, psychedelic, mystical? What about hyperspace, after all? What about the invisible world? Sacred medicines? Has she seen the self-transforming mechanical elves for herself? Her delayed response seems to indicate that Earth-our human, terrestrial dimension-or perhaps these two art shows more specifically, are in fact where the magic is really happening.

“You mean ‘the Mundane Plain,’ ” Klea eventually offers with a humble, skeptical and yet delightfully cryptic chuckle after a slight pause and yes, all in a slow, familiar beat poet drawl. “That’s what my brother calls it, though it’s really a quote from my dad.”

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.