Almost a decade ago, in my earliest days living in New York City proper (I’m a Long Island boy), I met a tall, quiet, slightly shy, longhaired artist at the coolest annual improvisational jazz-meets-blues jam on the Upper East Side. This was Justin Orvis Steimer. The party, thrown every year on jazz legend “Duke” Ellington’s birthday (April 29th), took place in the home of the late documentary filmmaker, Gary Joe Keys, who passed away in August 2015. Mr. Keys had directed a series of seminal Duke Ellington documentaries that solidified the director’s place in the jazz pantheon. My first NYC girlfriend, Leona, shared a birthday with Mr. Ellington, which endeared her to Mr. Keys for her entire life and certainly for the remainder of his. Leona’s mother, a Japanese high-fashion model in the ‘70s and ‘80s, was a long-time friend of Mr. Keys, which ensured an annual invitation and some overprotective, playful fatherly intimidation. Leona could sing, but she had terrible stage fright. However, for one night a year, Gary-hunched but ripe with authoritative swag-would grab her by the hand and drag her up with some of the best musicians in the country to sing an old jazz standard in her sensual, smoky voice.

Steimer was presumably dating (perhaps experiencing is a better word) the eccentric, supremely talented and infamous performance artist, director and photographer (pre-Dexter), Ventiko. Ventiko happily incorporated Leona (also a model) into some of her larger, composite, Renaissance nude, group portraits-bacchanals filled with friends, lovers, faux jewelry, doppelgängers and animals in various stages of the life cycle.

“Bacchanal,” 2012, 40 x 60 inches. Image courtesy of Ventiko.

Ventiko and Leona became friends. Several weeks later, the four of us met in earnest at Gary’s private jam, which saw young prodigies like Jon Batiste (now Colbert’s band leader) murder it with club gods and old studio staples. Steimer, her plus 1, who from what I recall barely uttered a single word, was drawing tiny little doodles on small, loose-leaf notepad paper in ballpoint pen throughout the evening. After several moments, he would hand you this small drawing, which was an impromptu illustration of your energy, spirit, vibe and overall metaphysical countenance. It was a little strange and seemingly pretentious, especially through the lens of a still reforming lax-bro, but there was something honest about the action itself and something disarmingly true in the drawings.

Ventiko and Steimer held it together for a little while longer. As did Leona and I, but ultimately, we parted ways. There was too much room to grow and we were all just kids in New York City-raw artists who could sense their niche but had yet to find their voice. Ventiko and I hung in there as friends, as I had begun to manage the now defunct Culturefix on the Lower East Side (pre-CBS Jon Batiste would blow our roof off and shut us down after sets at Rockwood Music Hall), which hosted her insane and highly memorable performance art series, the appropriately titled, Performance Anxiety. Ventiko also executed a series of portraits for my Interview Magazine interviews. We drove each other crazy. She would be an obvious handful (if you were Andre the Giant) and I would respond like the full-blown, recently passed R. Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket.

Years went by before I would see Justin again. During that time, I met the incomparable UN lawyer and activist turned art dealer, Catinca Tabacaru. In March 2015, Tabacaru was showing the work of Gail Stoicheff in her relatively new brick and mortar gallery at 250 Broome Street, now a shining light on the LES. This was Stoicheff’s Distressed Blonde. Stoicheff, who also works here and there with art dealer Mike Weiss and has been featured on his newish gates of the west newsletter, put me on Tabacaru’s radar as a press contact. Stoicheff’s more recent show, April 2018’s Little Miss Strange, blew past the mythology and returned to deeper archetypes, all bathed in fractal tie-dye and riddled with astrological Easter eggs and ancient feminist musings. The show was gorgeous, ambitious and totemic, but lacked the type of contemporary, personal exploration that would invite a hoard of contemporary press vultures.

Gail Stoicheff’s “One of Many Children (Temple of Apollo),” 2017-2018, oil, dye, and fringe on canvas and velvet_112 x 222 in. As seen in Little Miss Strange.

Catinca and I met at her gallery on the snowy opening day of 2015’s SPRING/BREAK Art Show, when the quirky, curator-driven fair was still located within the labyrinthian and weirdly wood-paneled Post Office space. Before heading uptown to the fair that same day, I found myself engulfed by Stoicheff’s looming painterly veils-monumental optical illusions which could be best viewed while lying on the floor of the gallery (Catinca’s playful and refreshing recommendation).

Gail Stoicheff’s “Fifi,” 2015, oil and dye on canvas and velvet, hydrocal metal chain, 96 x 72 in. From Distressed Blonde.

At that point, Tabacaru had a small roster of artists, something closer to a family. One of these artists was “Justin,” though a surname was never uttered, and therefore, I assumed I didn’t know this person. I had seen some digital images of “Justin’s” work. There was something familiar about it, however (in hindsight) the scale was blown up considerably, about halfway to Schnabel sizes. Huge, nebulous color forms floated on repurposed sails, stitched together tightly and confidently. The works were abstract but not expressionistic, illustrative, but not sloppy or overly masculine in that redundant, sophomoric, ejaculatory wet dream kind of way. There was control, intention and a strange, welcomed blend of maturity and naivety.

Justin Orvis Steimer’s “Eskimo,” 2014, oil and acrylic on Indian silk and cotton, 68 x 52 in.

Only weeks later, Tabacaru was contemplating an ambitious cross-cultural residency program in Harare, Zimbabwe for all of August 2015. She would be taking the Brooklyn-based “Justin,” the Russian-born multi-media artist Rachel Monosov and the young, sensitive, Surinamese draftsman, Xavier Robles de Medina. This bourgeoning collective would descend upon Dzimbanhete Arts Interactions, a difficult to define cultural center built on quiet but spiritually and politically charged plains roughly 25 km outside of Harare’s city-center. The residency hub is located on the largest granite formation on the African continent and shares space with sacred, government protected caves featuring ancient tribal expressions going back thousands of years. It was the type of trip that could use an adventurous young journalist to witness the tree falling in the forest, so to speak. It was settled; I would join Catinca’s art family and the creative citizens of Harare for the last week of their residency.

This is where things get tricky, as the American press world is rather conservative when it comes to discussing shamans and things of that sort. Without going too in-depth, the M.O. of Dzimbanhete goes something like this: Artists, musicians, curators and other travelers arrive, are greeted warmly by DAI’s Director, Chikonzero “Chiko” Chazunguza and Chief Cultural Director, Jonathan Goredema, aka Samaita, and the artists state their intentions. This doesn’t differ widely from standard residency programs, which often involve self-exploration, an anthropological appreciation of setting and culture, and eventually, the production of artwork. The residency would eventually culminate with a small, on-campus exhibition.

DAI’s unique, central conceit involves a scheduled personal “consultation” with Samaita (Gordema’s spiritual name) in his “office.” To be clear, sacred medicines are not involved, which makes the results or rather, the bountiful fruits of this consultation, all the more remarkable. These fruits are illustrated rather clearly on Tabacaru’s gallery website. Exhibitions at The National Gallery of Zimbabwe, multiple related shows at her New York gallery, museum acquisitions, a new gallery co-run by Tabacaru on Dzimbanhete’s sacred grounds, a seismic political shift in Zimbabwe’s leadership, representation in the Venice Biennale; even a marriage can be boasted. What you won’t see-unless for yourself-is the transformative one-two punch of Samaita’s astounding abilities as a community moderator and spiritual medium, or Chiko’s indispensable role of translating (quite literally) these discoveries into each artist’s respective practice. Evolutionary leaps are inevitable and undeniable.

Justin Orvis Steimer’s “Yapci,” 2015, oil, acrylic and ink on polyester shirt, 29 x 23.5 in.

The night before Catinca departed for this first Zimbabwe trip, she insisted I meet this “Justin,” her soon-to-be traveling companion, at one of her favorite downtown haunts. When I arrived, I immediately recognized the same shy doodler from Gary’s super-jam. It all made sense. There wasn’t much to catch up on, as the reunion seemed inevitable. There was a bit of shared, guarded apprehension, probably due to the fact that we were both a bit more relevant in the “art world” at this point and seeing each other years later was almost implicating, as we were living reminders of our earlier, younger, more formless, unrefined selves. Tabacaru, who (through her presence alone) invites internal alpha-male rumblings, delighted in this of course.

In Zimbabwe, I became more familiar with Steimer and simultaneously, his process, which now involved sitting with his subjects over a longer period of time. Though Steimer spent much of the residency working alongside Admire Kamudzengerere, who would later go on to represent Zimbabwe in the 57th Venice Biennale (2017) and collaborate with Monosov on the criminally under-appreciated performance and photography series, 1972, it was Justin’s thesis painting of Samaita (executed in the latter’s spiritual hut) that truly validated both his own process and Samaita’s profound shamanic capabilities. Throughout this residency, Steimer exuded a silent, humble leadership quality, which a loudmouth American writer learned to appreciate and even now, emulate. Though Steimer was already on his way towards becoming something of a “guide” himself, his ability to tap into his subject’s essence, whether on repurposed material or in “real life,” experienced a hyperspace leap that was exciting to behold. Simultaneously, I believe Steimer witnessed this in myself as well. Such is the magic of Dzimbanhete.

Steimer’s 2016 September show at Tabacaru’s New York Gallery, cave paintings of a homo galactian, continued the artist’s exploration of the “spirit” on a series of boat sails framed over walls painted a shade of blue quite reminiscent of Harare skies. The works, which could be described as “meta-figurative,” were displayed publicly when, in America at least, artistic preference was paid to works tackling identity politics, which includes admittedly essential conversations regarding oppression and industry representation. The truth is, as Americans especially, we are not ready to explore the reality that we are all divine beings currently sharing this crazy life-supporting rock (for now) in this particular dimension, but rather exist as a series of disparate tribal factions, rendered as such due to archaic global and interpersonal maneuverings built upon the worst behaviors we can exude, and continue to exude, as high-level primates scrambling for resources. Similar tribal infighting is extremely prevalent in Zimbabwe, with deep class and tribal distinctions buried deeply beneath a layer of post-colonial despotism, globalism, and gross economic uncertainty.

How can we break through the fear of the other if we can’t dispense with the same fear, stigma and prejudice that prevent us from utilizing the tools that could help us to do just that? Art still is and must continue to be the gateway drug. What else is there? Catinca knows this better than most gallerists in the West, this idea that we must become sophisticated enough to tackle both the Earthly and the Heavenly. This is evident in her programming, perhaps best expressed with Coco Dolle’s performance series TRANS-ville, which Tabacaru graciously hosted within Stoicheff’s recent, broadly cosmic, psychedelic, deeply philosophical exhibition.

TRANS-Ville: Act V, Terry Lovette, 5/5/2018, Photo by Olimpia Dior.

We’re currently (obviously) at a cultural and spiritual crossroads. For young, white, male, American artists who have been privileged enough to slip into and travel to other, non-corporeal realities-which requires courage, physical and mental dexterity, and a massive leap of faith-the recognition of oppressive, systemic fear in the spiritually and intellectually constipated, after a point, seems downright alien and therefore, incredibly alienating. For Steimer, also an occasional DJ who spends much of his time in his Brooklyn studio, located within a cavernous repurposed schoolhouse sanctuary in Brooklyn (the living room is a dark grey, hollowed-out urban Maloca), he can only return to his art and its potential to effect change. Each of his paintings serve as a singular catalyst for deeper thought and personal transmutation-each art object the equivalent of ten thousand picket signs.

This is why I leapt at the opportunity to have my meta-figurative portrait done by Steimer. I was instructed to bring in whatever personal material would serve as the canvas. I chose an old Burberry trench coat I purchased from a dubious vagabond in Union Square over seven years ago for shockingly little money, guilt be damned. This uninvited street merchant had interrupted an emotional, false-breakup between Leona and I, as we were beginning to drift. This NYC intervention bought us another year. The coat, a trademark Burberry khaki, was too big at the waste and short in the arms and was languishing in my over-packed closet. It seemed like the right material to bring things full circle.

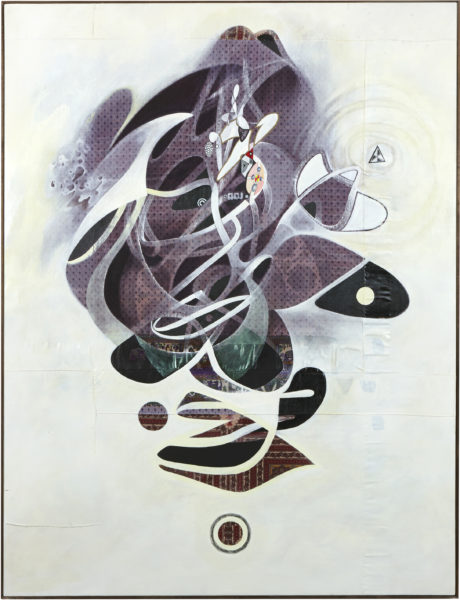

I visited Steimer’s studio three times, once for the coat’s deconstruction, the second, for Steimer to process my presence and energy, and once more for the finishing touches (a more intricate dimension). Each visit involved an exchange of ideas, a clash of Freud and Jung and the frustrating nature of the only big question left for us to discover: What came first, the archetype entrenched in some inter-dimensional objective reality, or the symbol, routinely rendered by curious human hands across multiple millennia? What is left for seasoned psychonauts if not the seemingly impossible challenge of defining the demiurge?

I saw the completed work, my portrait, on Monday, June 18th for the first time. It is vibrant, bold and fully varnished, shimmering like the metallic, blood-like sap of the Kapok Tree and stitched together like a Buffalo Bill skin-suit. It defies easy categorization. The painting and the process, yes, invites equal parts cynicism and unbridled optimism. For Steimer and myself, it’s difficult to discuss or critique the finished work. Where the painting will live remains to be seen. It simply exists now as a quiet celebration of an undying, unifying life force expressed through a singular vessel, of consciousness mingling with the (for most of us) invisible animaculae that swirl, dance and whisper around us always. It’s an appeal to our higher selves and don’t we need it.

On July 4th, at 50 Golborne in London, Steimer will join his Zim brother in art, the sculptor Terrence Musekiwa, for The Watchers, a joint exhibition that will build from a creative conversation the pair started during the 2017 launch of Catinca Tabacaru Harare. Later this summer, Steimer will return to Zimbabwe with Tabacaru and her growing, elevated, international brood to reconnect with their spot-on totems, ancestors, guardian spirits, and especially their gracious, talented African hosts, to dive deeply and fearlessly, once more into enriching, enchanting uncertainty.

Justin Orvis Steimer’s “kurt (defining the demiurge),” pure pigment, oil, acrylic and ink on gifted overcoat, 28 x 42 in.

Justin Orvis Steimer & Terrence Musekiwa

‘The Watchers’ at 50 Golborne.

PRIVATE VIEW: July 03rd, 2018 6 – 8.30 pm

EXHIBITION: July 4th – July 28th 2018

50 Golborne Road

London, United Kingdom

Phone:+44 (0)20 3441 8980

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.