Bubble wrap owes its proliferation to the computer industry. Initially it was designed as a type of funky wallpaper which nobody in the Eisenhower era wanted to buy. But in 1959, after lying dormant for a few years, it was realized that this would be the most effective protection for the transportation of computers—especially the IBM 1401 variable wordlength. As folks who work in galleries know, bubble wrap has also become the de rigueur accompaniment to art pieces when they are transported.

It was, in fact, the cavalier attitude toward bubble wrap at art galleries which triggered a type of moral or environmental awareness in artist Bradley Hart. He realized this material was so ubiquitous and commonplace that even folks in the field of art, who are supposed to be sensitive to environmental and social issues, were not thinking of the consequences of using and casually discarding this material into eternally stagnating inorganic landfills. Using bubble wrap as his means of expression became his response to this situation of wastefulness.

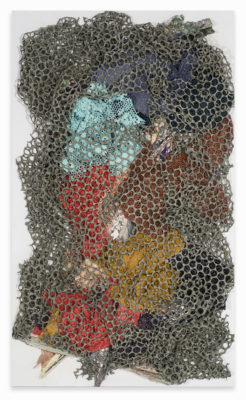

Hart uses bubble wrap kind of in the way a street artist might use a wall. Indeed, the Berlin Wall before its takedown by the people of Germany is even one of the images in the show, as, perhaps, a self-reflective gesture. But Hart’s refusal to allow something to go to waste and his desire to make use of the most useless type of castaway thing requires that he engage in a super-laborious process of creation. He injects acrylic paint into each cell of the bubble wrap, cell by cell, methodically, in what might even be called a type of proletarian process art. I’m assuming Hart doesn’t pay some guy $10/hr to do the injecting—he himself goes through what most would find to be an incredibly tedious process to get his final result. He’s basically a ‘worker-artist’ or he’s like a Japanese full-body tattoo artist, engaging in a repetitive process of injecting ink over and over again into human flesh. Yet, he could also be considered to be in the tradition of the great tapestry makers of the Middle Ages, who worked with a negative image and who looped thread continually from the negative side to the front side of the tapestry and back again to get large narrative images from thousands of little stitches.

In the gallery notes pointillism is mentioned and he also seems to follow from this route. The whole point of pointillism was to apply unmixed colors in little dots so that the human eye would do the mixing if you stood at the right distance from the painting (three times the distance of the diagonal of the painting). By not mixing the colors on the canvas, you get greater brightness. Yet I’m not sure Hart is shooting for brightness in these pieces; I interpreted his work as, mostly, process art, as a way of taking something valueless and inconsequential and finding a hidden quality and potential in it that lay unexploited due to the extreme effort necessary to utilize it.

Hart is, however, motivated by his environmental concerns and is willing, therefore, to take whatever time is necessary and he brings out an expressive potential in this material in a similar manner in which bubble wrap’s protective potential was inadvertently discovered. He reveals that within the bubble wrap itself was a hidden emergent quality for the transmission of meaning allowing this material to be saved from the landfill. Hart’s art is also a type of victory over an obstacle, the obstacle being the nature of the bubble wrap which allows the transmission of visual imagery but only through a laborious effort that ultimately requires the active collaboration of the human eye.

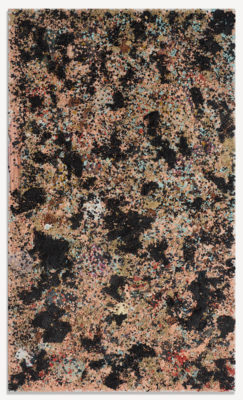

Hart doesn’t waste anything. In order to get each cell full of paint he has to over-inject into each cell. This causes paint to seep out the back of the bubble wrap. Hart then peels this layer off as a second painting. So you get the image of the object and then an abstract, dripping, flowing image derived from the image of the object at the same time, which calls the legitimacy or primacy of the visual image into question and points more toward the importance of the effect of imagery on our inner reality, as it interfaces with our experience, memory and emotional responses.

Hart also seems to take excess acrylic paint from his floor, pallet, tools etc. and applies them to a canvas in what the gallery notes refer to as a ‘collage’ style. So at first Hart shoots for realism through a difficult means to convey realism but this process results in more and more expressionistic pieces which impugn the notion of a separation of objective and subjective reality and point, instead, to a unity of inner and outer experience.

Descendants is on display at Anna Zorina Gallery until April 4th.

Daniel Gauss is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin/Madison and Columbia University and a long time resident, educator and gallery hopper in NY City. He is also the author of ‘New York City Sucks, but You’ll Still Want to Come Here’. He believes there is immense, important and transformative meaning in art and tries to promote the most dedicated emerging artists.