The success of painter-turned-filmmaker Julian Schnabel’s biopic At Eternity’s Gate depends on who you are asking. Someone expecting exciting revelations or fresh insight on Vincent Van Gogh would most likely be disappointed, however, Schnabel never made such claims.

Though the film has been criticized for merely continuing to stir the already existing pot of mysteries haunting the memory of the artist, its approach to recounting the last few years of Van Gogh’s life and the creation of some of his most famous works is empowering. Schnabel’s purpose wasn’t to educate viewers but to give them the opportunity to live these moments with him.

Willem Dafoe (Vincent Van Gogh) in Julian Schnabel’s AT ETERNITY’S GATE (photo courtesy CBS FILMS)

There were few to none feel-good moments. The only romance was Van Gogh’s assumed crush on Madame Ginoux, a woman later referred to as a prostitute. The artist was his own villain and most of the audience enters the film knowing a happy ending is unlikely. So, to have approached the film attempting to present new information on an icon, who has been studied for over a hundred years, would have been foolish, and the expectation of the possibility of it (without a sprinkle of non-fiction) is naive. What Schnabel does offer is Willem Dafoe.

Yes, Dafoe is sixty-three years old. Van Gogh died at age thirty-seven. But in an industry where there are 30-something-year-olds perpetually pretending to be high school students on TV, him being portrayed by someone with such an age disparity is, almost, appropriate for Hollywood. (Whether an older actress would have been considered for such a role is another discussion, though Van Gogh’s crush was probably much younger back then, too.)

‘You overpaint,” Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac) criticizes Van Gogh. “Your surface looks like it’s made of clay. . . . It’s more like a sculpture.” Dafoe carries this same sentiment throughout his acting, exaggerating every moment and emotion, bringing a multi-dimensional perspective to Van Gogh‘s pain, self-torment, and mental instability. It was by no means the performance of his lifetime, but it’s a performance depicting the artist we haven’t seen in this lifetime.

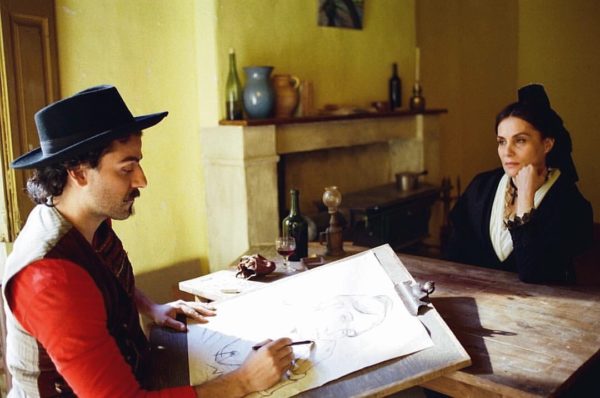

Oscar Isaac (Paul Gauguin) and Emmanuelle Seigner (Madame Ginoux ) In Julian Schnabel’s AT ETERNITY’S GATE (photo courtesy CBS FILMS)

The camera angles are shaky and confrontational. The viewpoint constantly changes from the eyes of the artist to a third-person perspective. The language shifts intermittently. The supporting actors, at times, only seem to tolerate and pity Van Gogh, including his art dealer brother Theo (Rupert Friend), whose financial and emotional support he is completely dependent on. Van Gogh’s anguish and desperation are overwhelming and obnoxious. The film delivers the palpable reality of what it was like to be an artist in a time where success was waiting for you to die.

This burden wasn’t lost on the artist, who towards the end of the film confesses to an unimpressed priest in a mental institution that, perhaps, his work is for people who have not been born yet. It feels parodical of a millennial believing to be born in the wrong generation because they happen to like 90’s rock. It’s a truth that would be awkward and egotistical for Van Gogh to be conscious of if Dafoe didn’t say it in such hopelessness. When his existence was based on two things: what he considered the only gift God gave him and the world to prove wrong, he needed to believe in a destiny harder to dispute in order to survive.

Whether Van Gogh was murdered or committed suicide, the reason for cutting off his ear, his love life or what led to the tumulous last few years of his life wasn’t relevant. Schnabel chose a narrative, but the brilliance of the film doesn’t substantiate from it. The success falls on the relationship created between the art and the artist. The abrasive use of color, the aggressive and relentless brushwork, and intoxicating subject matter parallel with Dafoe’s character, a Vincent Van Gogh often remembered but rarely introduced.

PG-13 | 1h 50min | Biography, Drama | 16 November 2018 (USA)

Showtimes

#AtEternitysGate

@CBSFilms