“I have returned to the scene of the crime, as I call it… That’s Indianapolis, Indiana. But I’ve lived in New York, California, London… I’ve ventured out a lot.”

Constance Edwards Scopelitis.

Though Scopelitis finds the political climate in Indiana, where she grew up (“I mean hello, we gave you Pence”) really interesting to “rub up against,” especially from, as the kids say, a “woke” perspective, she’s mostly excited about her ten, technologically savvy works currently on exhibit at the Cornell Art Museum in Delray Beach, Florida, a hop (Hollywood), skip (Fort Lauderdale) and a jump (Boca Raton) north of Miami.

The group exhibition, Tech Effect, which features over 20 artists and runs through March 2019, examines how technology, you guessed it, effects our very human lives, for better or worse. “The work I’ve been doing is about not knowing who your neighbor is and then drawing conclusions that make you treat people terribly,” says the artist, more interested in Man vs. Man as opposed to say, Man vs. Machine. Both are heavy subjects, but for Scopelitis, tech is simply a new and necessary vehicle to deliver an important and yet age old message to an audience with both acquired and congenitally short attention spans.

Last year, while exhibiting at Art Miami 2017, and showing (by way of her dealer) works that were considerably less “challenging” than what she proposed (“Some people cave and show the easy stuff”), she noticed that fairgoers of all kinds, with of course some deviation, give any particular art work (not only her own) about 3 seconds of their time and attention. It’s become common knowledge among film directors and editors that eyeballs soak up all the information on the big screen in roughly three seconds, which is usually when you see a cut. It makes sense then that modern audiences, used to staring at screens all day every day, treat contemporary 2D art like a disposable film still jpg on Google images; indifferent swipe, casual scroll and mindless swipe again. It makes even more sense that they (we) would want to transform these real world objects into a jpeg and dump it back into the grid. Rinse repeat.

“I’m trying to exploit the way people can really get lost in their devices,” says Scopelitis. “Nobody spends as much time with anything like they do their computer, laptop, pad, phone or video games. I used 3D game programs to get these things up and going on these touchscreen computers.” Scopelitis, happy to stick with the art making, reached out to some Generation Z coders to help bring her mixed media collage works and master graphite drawings to life. “The museum really got me, especially curator Melanie Johnson, who approached me at Art Miami last year. Juxtaposing the digital work next to photorealistic graphite drawings helps the viewer make the leap between the artist’s hand and what happens when looking at a simple 2D work.”

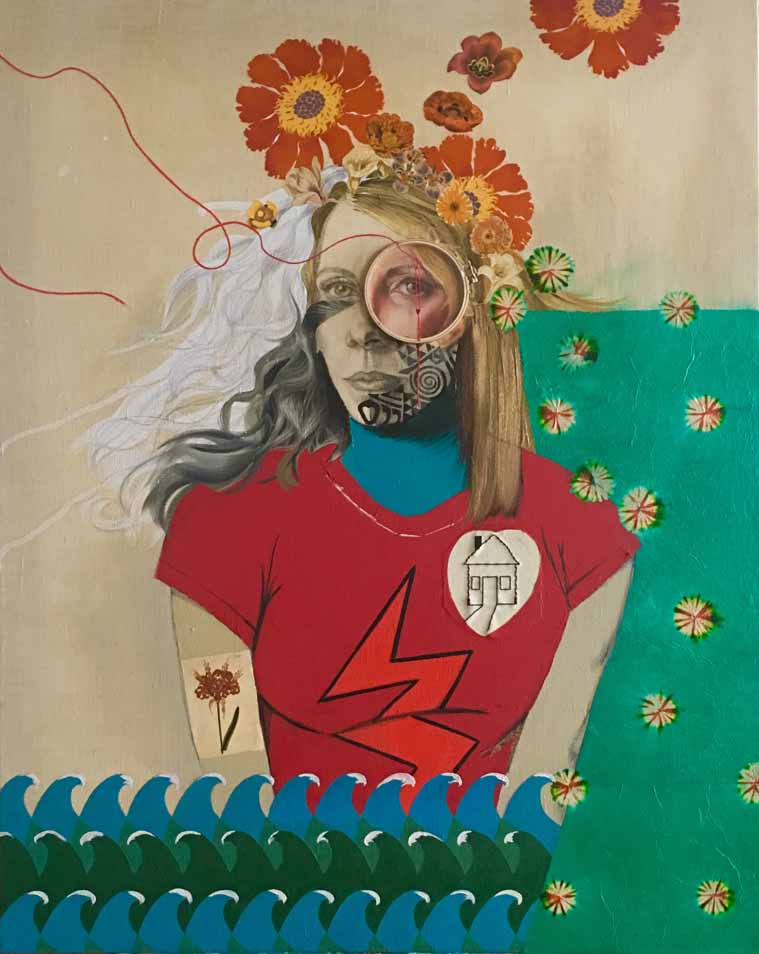

Scopelitis’ work is the living collage equivalent of a Terry Gilliam via Monty Python dream, a vogue ballroom-meets CNN digital, Neo-Renaissance explosion. Uninterested in decorative beauty (“You might as well take a landscape photo on your iPhone”) as opposed to “real content,” Scopelitis, a devil may care, but highly sensitive woman of a certain age, brings as much social justice fire as an artist fresh out of the Yale MFA program, but with considerably more experiential life perspective to bolster the message. What sets her apart further, is the deft artistic hand of a seasoned draftsperson, even if her end products often seem trapped in a state of uncertain flux. “I love watching people approach my work and dropping the headphones in front of my political videos. Many others have a real need to discuss it with me afterwards.”

“19,” perhaps Scopelitis’ most jarring, absurdist work for an absurdist age, features a pack of metastasizing wolves, a digital lupine militia wreaking havoc with assault rifles while a children’s choir sings (and screams) “Jesus Loves Me” in the background. “I think when there’s laughter in the midst of despair, it signals something is extra creepy or extra wrong,” says the artist. “The symbol of the wolf is to point out that most of our terrorist shootings are performed by home grown white boys in the United States, but no one can quite say that. It’s a “terrorist” if it’s a black sniper from the military or a Muslim bomber. But with white people, they can’t wrap their brains around this. The pack of wolves is about how militias can be gathered if you have enough disenfranchised young men. No parent wants to admit that his or her kid is a troubled loser.”

For the series featured in Tech Effect, Scopelitis was originally shocked and inspired by the shooting of Trayvon Martin by borderline sociopath George Zimmerman. “When he got away with it, I was like, ‘What the fuck?’ I mean stand your ground? Also, there’s this issue of me being a white woman. Listen, I was born to teenage parents and grew up in a one-room shack with outdoor plumbing. I’m not making that up.”

Scopelitis can recall the not so-Halcyon days of Indianapolis in roughly 1963, a few years before MLK’s assassination and how they set the tone for her interest in America’s more dark, toxic and endlessly perplexing underbelly. “As a young child, I was a witness to a cross burning,” she says. “It’s stuck with me my whole life. Dad had been in the army. One of his buddies was African American. He and his family lived in these starter homes, this mushroom house community. They had two kids, a boy and a girl-nice, easygoing people. We went for ice cream. My sister and I were in our jammies. Driving back, at the “T” at the end of the street, there was a cross, burning in the dark in their front yard. My sister and I started crying. We thought somebody hated Jesus.”

In Indiana, to this day, there is still quite a bit of “bible banging” as Scopelitis and others put it, a continuing and pervasive fear of the other. She can recall, in March 2015, our Vice President and former Indiana Governor Mike Pence pushing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA); legislation that would legally permit business owners to bar gay people from entering into their establishment, worried their exercise of religion has been or is likely to be substantially burdened. New amendments have since passed that offer greater protections to the LGBTQ community, but animosity on both sides remains.

“The older I’ve gotten, the more inspired I’ve become to say something,” adds Scopelitis. “In Indiana, younger kids go to school with each other and are getting to know each other. To watch an older person defend their black grandchildren is something.”

Something indeed, as passing on racism, sexism, bigotry, homophobia, xenophobia and other prejudices to the next generation, especially children, these otherwise pure, empty vessels, might actually be the clearest definition of evil, a word that’s often used too lightly. To operate as a progressive, politically minded artist out of Indiana, as opposed to LA, Miami, or NY, does seem admirable, if not downright essential.

So what about the homegrown, lone gunman or the festering alt-right human powder keg? It’s a bit more complicated than just staying involved in your child’s life, though it’s a good start. The mother of James Fields, 21, the Neo-Nazi driver who drove over and killed Heather Heyer, 32, and injured 19 other people after the “Unite the Right” gathering on Aug. 12, 2017, was just sentenced (as of this writing) by a jury in Charlottesville, Virginia, who recommended and secured a life in prison sentence (as well as an extra 419 years) after being found guilty of first-degree murder and nine other crimes against humanity. His mother, who was approached the day after the “Unite” fiasco by Vice reporters at her home in Maumee, Ohio, was completely oblivious to his warped ideology. Her ignorance seemed almost equally criminal. Complicit even.

“I genuinely have sympathy and empathy for those lost through the cracks,” says Scopelitis, aware that gunman like the expelled (never to return) Parkland shooter Nikolas Cruz was a foster kid (his foster parents both died in quick succession) otherwise abandoned by his parents and peers. “We don’t pay our teachers but we expect them to be police officers, social workers, educators. Look at New Towne. He killed his mother before he went to school and killed all those babies. His father was living with his brother up north. Mom was buying the kid guns because she didn’t know how to raise him. It’s a multi-layered problem. But nobody knows what’s going on more than the family.”

Scopelitis, a self-professed “hippy child girl” out of the ‘70s, as well as a studio rat (“No plants, no hobbies, no more hubbies”) who has been married and divorced three times (“I don’t want to put turkeys in the oven and I don’t want other peoples’ children sitting under the Christmas tree”), recalls discovering the fact that her only daughter, at 13 (she’s now an adult and a family therapist) had an eating disorder. “When I came downstairs to help my daughter get off to school-she was in 7th grade-I saw her and my brain cells expanded and I looked at a child who was not eating,” she says, her present tone recalling past shock. “Her neck was so thin, her head was bobbling on it, and her little collar bones were sticking out. I felt like it almost happened overnight. How could I not be paying attention? Boy those were rough years.”

Constance’s daughter now specializes in body therapy, not so ironically. What’s important is not the fact that the eating disorder went unnoticed for so long, but that Scopelitis quickly sprang into action when it was discovered. “I got her into The Riley Children’s Hospital (at Indiana University),” she says. “She was so pissed. I was just trying to get her to eat a sandwich. I had some guilt over this one.”

At 26 years old, several years after graduating from the same university (Indiana U, 1973-1977), Scopelitis was traveling the world, experimenting, adventuring and making art. “I ended up getting pregnant out of nowhere,” she says. “I was a grown-ass adult on the pill, but somehow became pregnant with a guy I didn’t know. We managed ultimately to co-parent to the best of our ability, but we never lived together. I didn’t know that he was an anorexic. He is a medical doctor. He’s in his 70s and he still doesn’t eat. When I took my daughter to therapy, she explained that he never had any food in the house.”

Art, ultimately, is about investigation, of caring about not just beauty or creation, but in the aggressive preservation of beauty and the celebration of creation as opposed to mindless destruction. It’s Dylan Thomas’ greatest quote, but expressed with paint, pixels, code, clay, wood, or fiber (and more) as opposed to the pen or typewriter. It’s about getting and staying involved. It’s about guiding technology and therefore civilization towards the better angels of our nature. It’s about the older generation staying hungry and maintaining a positive relationship with the generations behind them by creating a strong chain built with links of empathy and understanding as opposed to the weak binds of apathy and nihilism. It’s about honoring and challenging our elders. It’s about never giving up. It’s about fighting for what’s right. It’s about being the hero, not the troll.

“Artists,” begins Scopelitis, “by nature, have a large-enough ego where they have to put something out there that’s important enough to sacrifice for, to turn into an art form for the world to except, reject, ignore, never see or embrace. It’s not an easy world. I have rhino skin, but I’ve been at it for a while. Most of the time the word is ‘no,’ but the yeses are spectacular.”

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.