There’s nothing overtly didactic about 39-year-old artist Andy Mister’s solo show at TURN Gallery, New Dawn Fades. There are, however, 11 painstaking works on display featuring roughly the same number of representational images, each deftly rendered in incredible detail on monochrome paper using carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic.

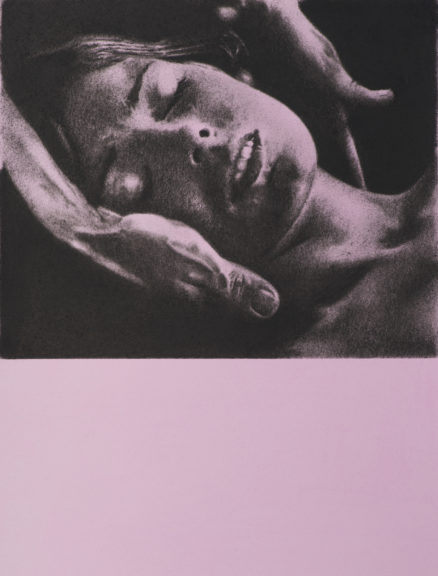

“Ascend,” 2018, 12×9 in, Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

The recent passing of Tom Wolfe, an at times controversial literary giant, undisputed master wordsmith and “new journalism” pioneer, provided a valuable, albeit somewhat unfortunate philosophical lens through which one could view Mister’s subtle but deceptively masterful exhibition.

Wolfe wrote a lot of first-rate books and articles, but the work most closely related to the art world is The Painted Word (1975), a critical response of sorts to Hilton Kramer’s Times review of Seven Realists, a 1974 group exhibition at the Yale University of Art.

In his review, Realism: The Painting Is Fiction Enough, Kramer wrote, “…to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial—the means by which our experience of individual works is joined to our understanding of the values they signify.” Kramer later noted that, while realism was flourishing at the time, it was doing so in an “intellectual void” and that the strength of realism lies “…in painting that is able to draw upon the resources of the representational function without relying on the easy evocation of a world beyond the painting itself.”

Andy Mister’s “New Dawn Fades” at TURN Gallery.

Wolfe being Wolfe, of course took things to the next level. In his personalized summation of Kramer’s short but impactful piece, he added, a bit more colloquially, “Without a theory to go with it, I can’t see a painting.”

Disillusioned by the dimensional shallowness of modern art and its avant-garde flag bearers (Pollock, de Kooning, Warhol), Wolfe deemed their works insufficient, their structural and thematic integrity overly reliant on the support of the literary (critical) supplement. Wolfe, perhaps with only the slightest “Radical Chic” dash of faux anti-Semitism (in The Bonfire of the Vanities, the story’s mayor was crudely nicknamed “Goldberg”), decried the crutch-like role assumed by the “Kings of Cultureburg,” a trio of insular male critics in the ‘70s (Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, Leo Steinberg) who Wolfe felt collectively wielded a dangerous and outsized influence over the industry.

It’s hard to argue that contemporary art especially doesn’t still live and die within the framing of this literary Panopticon. Just take a moment to download the compacted critical influence of New York Magazine’s senior art critic, Jerry Saltz and his wife, Roberta Smith, co-chief art critic at the Times (the first woman to hold the title). The Pulitzer Prize winning Saltz plays the everyman well, maintaining a reasonably open discourse with his adoring mass of followers, whether IRL or online. Though his following could rightfully be chalked up to his charm, obvious talent, and hilariously ironic anti-populist populism, it is still a reflection of a deputized, institutionalized, (former truck driver or not) post-modern extension of the highly coveted literary Midas touch Wolfe once criticized.

“3.1415926535,” 2017, 10×8 in,Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

Wolfe and Saltz actually shared honorary speaker duties at the 2015 Take Home a Nude silent party and auction at Sotheby’s where the ever-dapper Wolfe coined his last great art-ism, the “no hands movement” which makes fun of Richard Serra and Jeff Koons’ reliance on multiple gallery assistants to produce work. One presumes Wolfe lived long enough to watch contemporary (past-modern) art fulfill its destiny as he saw it; art morphing into literature “undefiled by vision.” That being said, one can’t help but wonder what he would have dubbed art’s most influential critical power couple and commercial validation key holders?

This is what makes Andy Mister so interesting, essential, perplexing, and at times frustrating, especially from the perspective of an arts journalist (hah!) or critic (gross!), he doesn’t want to provide any additional contextual supplements to an exhibition that probably, from his point of view at least, already gives too much away.

Andy Mister. Photo by Azhar Kotadia

“I spent a number of years doing intricate paintings of historically situated imagery; crowds, protests, burning cars and buildings,” Mister says in a cool, stretched-out beat poet droll. “People would inevitably ask, ‘What’s that from?’ For them, the story behind the image was important, as it was clearly pulled out of history. I got a little burned out on that. ‘What’s the story? What’s the event?’ ”

This pedagogical fatigue pushed Mister to take a break from presenting historically representational snapshots of conflict and revolt. Instead, he slid the creative needle towards something not entirely abstract exactly, but more archetypal maybe. This shift manifested most “concretely” in the recent past and present as mountains.

“New Dawn,” 2018, 28×22 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

Annika Peterson, TURN Gallery’s founder and curator, helped fuel this transition when she paired Mister’s new “landscape” works with artist An Hoang’s abstract paintings. This was late-October 2016’s Shifting Terrain.

“They’re very different artists,” says Peterson. “Andy was the hyper-real and An [Hoang] was a memory of nature. But they shared a unique color palette and a poetic sensibility.”

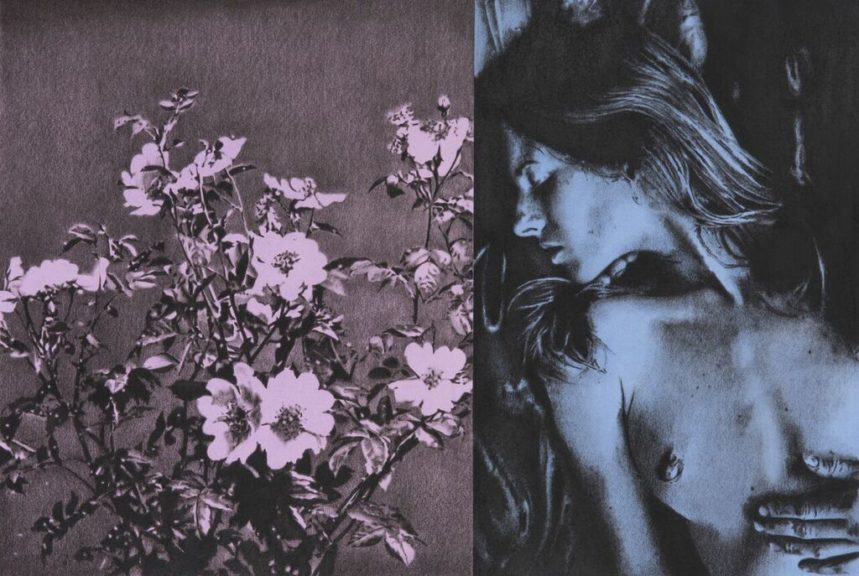

“The Double Dream of Spring,” 2018, 16×23.5 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

In 2018’s New Dawn Fades, mountains are back, two mountains to be precise. However, Mister also brought back his puzzling, historical cannon fodder as well. These human faces, bodies, spaces and objects, all dimly recognizable, many of them hollow-vacant, intermingle with Everest and a veiled, more mysterious crag to form a juxtaposed narrative (if you wish). The show and work therein could probably do this without the need of any supplement, whether that’s a show title, work titles, a press release, an artist manifesto, or in a more macro sense, this very article you’re reading or more likely not reading. As brand-name editors (click-bait merchants) like to remind their considerably more interesting brethren that the gallery review/artist interview is dead on arrival, all with a straight face and blood on their fingertips.

“[French-Algerian philosopher] Jacques Derrida has a whole thing about the ‘supplement,’ ” Mister utters in an apologetic tone, knowing he’s most likely set off a philosophical avalanche out of which there is little hope for escape. “If you look in a book, there’s a photograph, but next to the image there may be a caption. The caption is the supplement. It [the image] doesn’t have a whole meaning; it needs the caption to give it a wholeness.”

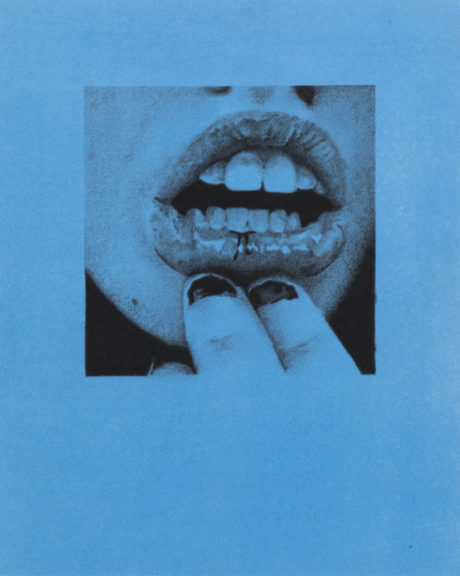

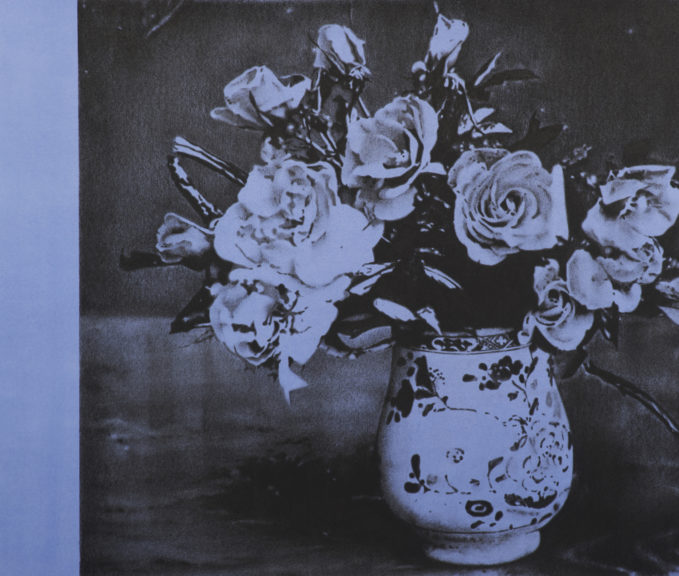

“Blue Arrangement,” 2018, 21.5×18 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

In Derrida’s Of Grammatology (1967), the philosopher asks, “What is meaning? He even goes far enough to say, “There is no ‘out of context.’ ” It seems like the super-laid back, artistically laissez-faire Mister would be totally down with this approach. Take what you want from my raw pagan art object offerings-they belong only to the public and the art gods, he seems to (not) say. Or, if you prefer to hear it from the man himself: “I don’t really go into anything having a real formed coherent notion of exactly what I want to say.”

Any art writer worth his, her or their stones (metaphorical) can see that New Dawn Fades is not only directly infused with a treasure trove of historical and artistic supplements, it’s also a collective consciousness fever-dream indictment of the viciously optimistic American socio-political cycle. But is Mister pointing to our better angels or our persistent devils? Even more whittled down, it’s an outward psychological explosion of the Andy Mister tripartite-the id, ego and super-ego. “I don’t think I can psychoanalyze myself,” Mister offers rather refreshingly, though either he’s lying, playing coy, or an undiagnosed idiot savant. “I don’t have a lot of self awareness in that way. There are things that interest me and I get obsessed with them. I mess with them until I exhaust them. I get so into it that I can’t pull out to see the larger picture. Anything I do with my work, however, it’s always about me.”

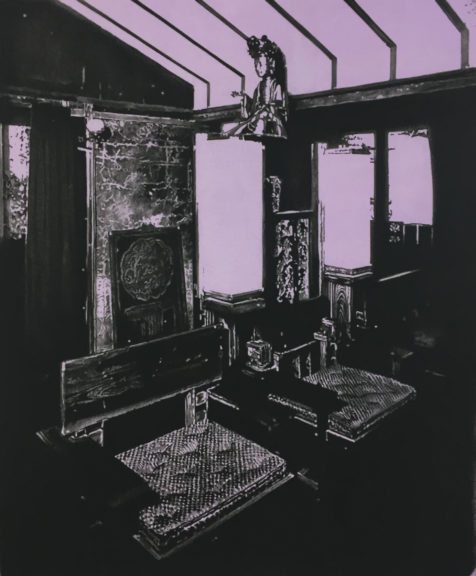

“Room Tone,” 2018, 22×18 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

Contradictions in art are often welcome, as they’re a precursor to intellectual and emotional conflict, which is at the heart of any good work of art really. Also, to be fair, over the course of an hour, Mister was mercilessly poked and prodded enough that he eventually relented in providing some personal context to his work and the thought process behind the curation of titles and images. Therefore, though he would seem to side with Derrida and other poststructuralist thinkers, in that there is no unequivocal structure or meaning to his 11 chosen works and related imagery, Mister had this to say: “The titles in the show are from books, songs and albums, mostly from when I was a kid. That’s always been the most interesting stuff to me. It’s the world I always used as a lens to view my own life. I’m always interested in how those references affect the work even when they’re not directly related to it.”

The show’s title, New Dawn Fades is a Joy Division song, for instance. In a haunting, but gorgeous 2018 painting that shows the dreadfully empty back seat of JFK’s convertible murder vessel, Mister affixes the winky-winky title, Death of a Ladies’ Man. “I don’t really know how a person off the street might react to that painting,” Mister says. “They might create a whole story around that. If they are a fan of Leonard Cohen, they’ll know the reference (it’s the name of Cohen’s 5thstudio album), but they might just know it’s a JFK thing. By being focused on the details of the imagery, it forces the viewer to stop for a minute and spend a little time when maybe they wouldn’t otherwise.”

“Death of a Ladies’ Man,” 2018, 28.75×22.5 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

Real students of macabre history might recognize the frazzled visage featured in It’s So Hard to Know Who’s Going To Love You the Best, 2018, which also happens to be the name of the 1969 debut album by American folk blues musician Karen Dalton. Dalton, a Cherokee Native and friend of Bob Dylan, died from an AIDS related illness in 1993. Strangely, the woman in the painting sporting the Lady Macbeth eyes is Claudine Longet. “She was married to pop singer Andy Williams, but is better known for killing her ski instructor lover, Vladimir “Spider” Sabich [at his Aspen Colorado home in 1977],” Mister explains. “She shot the lover, then claimed that she did it accidentally. Got sentenced [negligent homicide], but didn’t get much jail time. Claudine was a schlocky French chanteuse [and friend of the Kennedys]. Her most popular song was “Love is Blue.”

“It’s So Hard to Know Who’s Going to Love You the Best.” 2018, 14×11 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

In Mister’s exquisite, 2017 painterly depiction of Mount Everest, the title of the work, Lost and Safe, comes from the third album by American music duo, The Books. When the early 20th century French novelist’s René Daumal’s bizarre literary allegory, Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing (a major influence on Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1973 film The Holy Mountain and countless other works related to metaphysical alpinism) was referenced, Mister had this to add: “I think that’s also the name of an awesome record store in LA.”

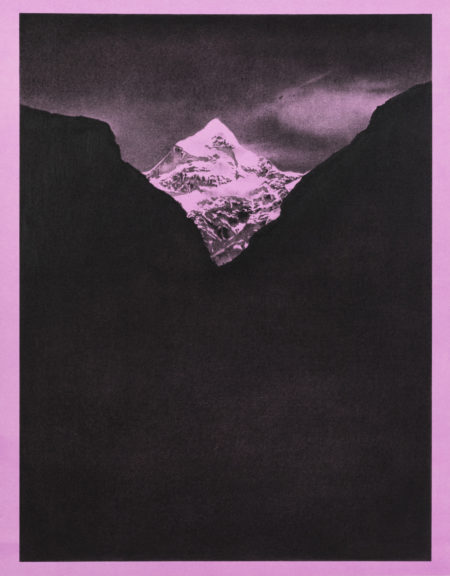

“Lost and Safe,” 2017, 29×24 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

Much of the lo-fi aesthetic seen across Mister’s work is a direct reference to the DIY, 7-inch records that came out of the punk scene in the ‘70s, ‘80s and ‘90s. For Mister, the gritty, monochrome vibe of his work speaks to the evolutionary narrative of the Xerox machine, which developed out of early silkscreen technology. His life and work are about, not just refinement, but vision made manifest. “It’s very quotidian, maybe,” says Mister, “but I’m interested in the results and figuring out whatever I have to do to get there.”

As Daumal states in his trippy little book, this approach is not so dissimilar to climbing a mountain. There’s a real quantum reality element to, let’s say, seeing yourself at the top of a mountain as well as envisioning all the distinct elements of a painting before a single mark is made. It’s almost all about projection. Why almost? Because projecting is not enough, you must paint. You must climb! This invitation for projection and subsequent adventure, whether physical or emotional, is then extended to the viewer. This is why a painting of a mountain, a monumental archetype, when executed well and with real intention, can be incredibly inspirational, powerful-almost hypnotic.

Mister credits a portion of his mountain infatuation to his artist friend Charles Lutz, who gave him a photography book by famed mountaineer Francis Sydney Smythe (1900-49). Around the same time, Mister was infatuated with the work of West Coast artist and musician, Lynn Foulkes and his wild, hybrid assemblages, disturbing portraits and impeccably painted, monochromatic landscapes of the American West. “At the time, I was thinking, ‘How can I engage more with the natural world?’ Foulkes’ rock pieces were very inspirational, like a guidepost. I actually did one big mountain piece named after him in another show.”

Andy Mister’s “New Dawn Fades” at TURN Gallery.

Before returning to Freud, one more crack at Derrida. Much of contemporary art’s collective literary supplement is now almost entirely informed by identity politics, which contemporary philosophers like Dr. Jordan Peterson blame almost entirely on the postmodern Derrida. The latter’s reliance on Semiotics and phenomenology, a method of philosophical inquiry that rejects the “rationalist bias” that has dominated Western thought since Plato in favor of a “method of reflective attentiveness that discloses the individual’s lived experience” has found an appropriate home in the contemporary landscape (see: Specters of Marx, 1993).

Art being a worthy vessel to disseminate empathy, especially for marginalized people, is in many ways a testament to the power and value of art itself. What makes Mister and his show interesting is the fact that he and his work seems to welcome Derrida, but ultimately, Freud and the late Tom Wolfe are equally, if not considerably more welcome at the table.

Annika Peterson of TURN Gallery. Photo by Azhar Kotadia.

For a white, American man close to 40 who emerged unscathed from a decade of, let’s call it, “hard partying”-Mister has checked his privilege-the artist is freed up to explore not only man’s greatest archetypes-the mountain, the West, God, mortality-but his own human experience outside of a compartmentalized tribal experience. It might not be the du jour perspective, but in the steady hand of Mister, it remains awfully valuable.

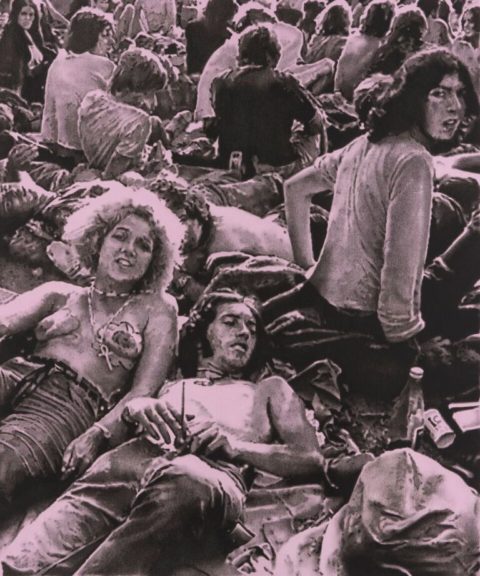

This begs the question: Without the overt polemics of identity politics, art’s most conspicuous and pervasive “theory,” would Wolfe be able to “see” Mister’s works? One would hope, as much of Mister’s works touch upon another of new journalism’s greatest offerings, that being Hunter S. Thompson’s drug-fueled Gonzo lament for the death of the counter-culture movement (Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream, Random House, 1971), the still receding high-water mark reached at Haight-Ashbury, the shadow of which can be seen in Range Life, 2018, which depicts a bunch of hippies lounging care-free at a music festival. Woodstock, Camelot, Obama’s 2008 victory, all for what? Fear and Loathing in Mar-a-Lago?

“My parents were big hippies,” says Mister, who also claims his father is a staunch communist. “They were involved in the civil rights movement and campaigns for nuclear disarmament. I’ve always been sort of enamored of the ‘60s protest ethos and it does feel like that is something that faded.”

“Range Life,” 2018, 36×30 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

Mister goes on to recommend Thomas Franks’s book, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (University of Chicago Press, 1997). “It’s all about how advertising in the 1970s co-opted the ethos of the ‘60s, then packaged it and used it to sell products. They defanged it. A lot of the prospects of the ‘60s were systematically undermined and ridiculed. For me, I grew up in the punk-rock world and I was always distrustful of hippies. All of my anti-authoritarian impulses arise out of the ‘60s epoch. I feel a lot of genuine respect for that massive shift in culture.”

“Range Life,” 2018, 36×30 in. Carbon pencil, charcoal and acrylic on paper mounted on panel.

It’s sad to think that a similar agenda might be in play in the art world currently, especially considering we are clearly in the midst of another tectonic shift. It’s slightly difficult to imagine what punk rock really looks like currently, if only from an ethos standpoint. Perhaps it looks something like Childish Gambino’s “This is America.” In fact, that could have been an alternate name for Mister’s show, just viewed through a considerably wider and yes, whiter lens.“It’s easier for me to read Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (The New Press, 2010) than watch that video,” says Mister when this notion is presented to him. “That wasn’t for me.”

Mister also recently became a father. Much of the work in New Dawn Fades was made during the last leg of his wife’s pregnancy. There seems to be a lot of fatherly anxiety on display, which begs the question: Is Mr. Mister happy about the America his five-month-old son Elliot was born into? “Definitely not,” he says.“The global biological collapse that we’re fueling is the scariest thing to me, more than the wars. In fact, I wanted to call the show New Age. It was discussed but I thought it could get misinterpreted. I really am a firm believer that [new age] stuff (and therefore the work in New Dawn Fades perhaps) could actually help people. I hope there is some sort of redemptive moment. I really do.”

New Dawn Fades runs through June 10th. TURN Gallery is located at 37 East 1st Street, New York, NY 10003.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.