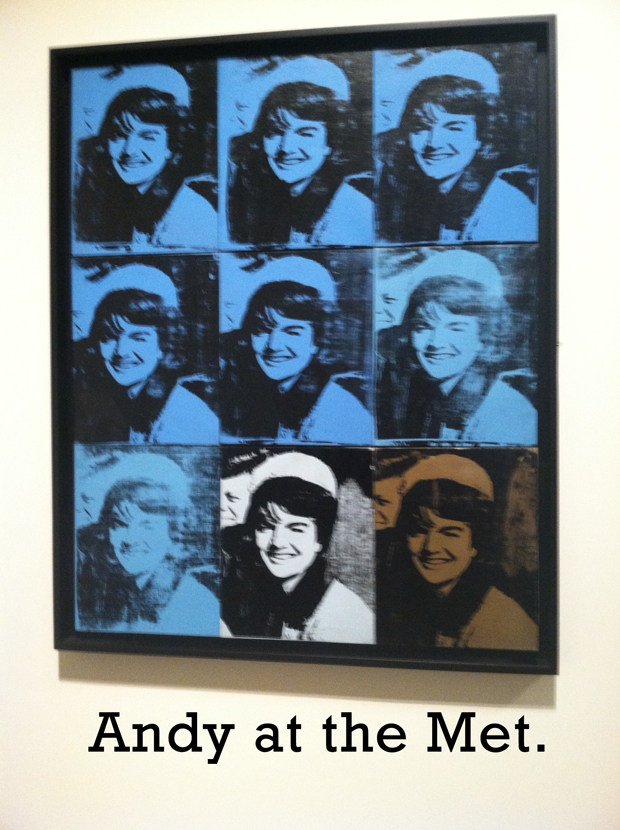

All I know about Andy Warhol I learned from the album Songs for Drella, the movie Basquiat and his brief, fictional cameo in Oliver Stone’s The Doors. I’m the kind of person that the Metropolitan Museum of Art had in mind when they curated the recently closed exhibit, “Regarding Warhol: Sixty Artists, 50 Years”: someone too star struck by Brillo boxes, Jackie O silkscreens, and sunrise over the Empire State Building to care about discerning a connection between the various artists and works.

The show attempted to break down its daunting concept into more digestible themes, but the overstuffed presentation of nearly 150 works by 60 artists in a kaleidoscope of colors, feelings, and forms had the dizzying effect of a grocery store or TV commercial break. Judging from Warhol’s proclivity toward consumerist sources of inspiration, he very well may have preferred it this way.

Michael Del Priore/Quiet Lunch Magazine.

The most visually striking moments were often the ones where the dialogue between artists turned into debate. Warhol’s “Orange Disaster #5” puts death at a distance, creating a catharsis through screen-printed repetitions of an empty electric chair, whereas Jean-Michelle Basquiat’s neighboring painting “Untitled (Head)” makes you look death square in the face of a battered and bloody black man. The grotesque black and blue stitches, shattered yellow teeth, and ferocious outrage of Basquiat’s piece is a shocking compliment to the grainy seriality, blaring metallic tone, and foreboding isolation of “Orange Disaster #5”.

But when you look past the exhibit’s stodgy commentary about Warhol capturing the materialistic idolatry and eroticized violence of American culture, you sense a prevailing tone of childlike innocence. The neon colors of “20 Marilyns”, the rule-breaking whimsy of re-appropriated images in “Baseball”, the implicit humor of “Piss Paintings” being in a museum – it all seems like the work of a Shakespearean fool poking fun at how seriously we take ourselves.

Michael Del Priore/Quiet Lunch Magazine.

Nothing drives home this point more than the culminating piece of the exhibit, which is a reprise of Warhol’s 1966 show at the Leo Castelli Gallery. You turn a corner and see a roomful of children swatting helium-filled silver clouds that fall gently from the ceiling. Fluorescent yellow wallpaper polka-dotted with life-sized pink cow heads sets a serene but phantasmagoric atmosphere that’s amplified by the background music of the Velvet Underground & Nico’s “All Tomorrow’s Parties”. Moments like these force you to stop trying to parse the metaphors, stop deconstructing Warhol’s gargantuan historical figure and remember how much fun it must have been for an odd young man from Pittsburg to find a home in a place like New York City. That’s something everyone should get to experience, even for just 15 minutes.

Written by Michael Del Priore.↓

Mike Del Priore (n.): musician, writer, voracious media consumer.

Michael Del Priore lived at a Spanish seminary for a year. When he returned to America, he heard John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme and everything changed. The idea of music as prayer inspired him to believe in the transformative and ennobling power of art in all its forms. He sometimes lives this belief as a musician and others as a writer. Either way, the one thing he knows: “beauty is truth, truth beauty”.