There is art that comes from the very depth of your existence. Works that dig deep and unearth a water table of history and self-discovery. Works that are not just awe-inspiring results but showcase a painstaking process in which an artist excavates the priceless relics within themselves.

Remains from Adebunmi Gbadebo takes us on a journey of knowing. When you walk into Claire Oliver Gallery, a certain gravitas greets you at the door. You immediately sense that this exhibition is saying something as it commands you to open your heart and listen with your eyes.

“I don’t want to assume that I’ll know what each person will take away after seeing this show. But I do hope they walk away feeling that I put a lot of care into this work and that through my own practice my ancestors are loved and not forgotten.”

– Adebunmi Gbadebo

Harlem, USA, is a hotbed of culture, and Gbadebo’s Remains finds itself right at home. It manages to be minimal and immersive. This is a degree of duality that is not exactly easy to attain. Nevertheless, Remains, while rooted in slavery, transcends time-tested trauma to create a more meaningful narrative that genuinely captures the Black condition. As a visual dissertation of our diaspora, the exhibition succeeds in reclaiming our history. It is all a picture imperfect portrait of the collective contemporary consciousness that imbues people of color. It is an unshackling of the mind, body, and spirit. Remains is not an exhibition about slavery but a conceptual gateway to liberation.

Through present-day efforts, Gbadebo is taking the debris of her past, upcycling them, and crafting the foundations of a new future. She seems to have a foot in both worlds. Recently enduring her mother’s death–along with her grandfather and uncle–she found something meaningful in processing the loss of her matriarch and others. Remains serves not just as a monument to mourning—it is a testament to transmutation.

Gbadebo encountered an obstacle of grief and molded it into an opportunity to heal, a feat that we all attempt to execute at some point in our lives. It is that very element that allows the exhibition to appeal to not only the Black condition but the human condition as well.

We paid a visit to Claire Oliver to view Gbadebo’s Remains and caught up with the artists to discuss the anatomy of the show and what makes it tick.

Remains looks to be an exhibition with a journey. Can you tell us about that journey? What are its origins, its turning points and its destinations?

“Prior to 2020, I worked primarily in hand-made paper. In this True Blue series, named after True Blue Plantation where my maternal ancestors were enslaved and currently buried, I would take cotton, human hair, denim, hair dye, and archival prints and create sheets of handmade paper as my way of creating a new document or archive of these histories of slavery. I was doing this series but knew that to fully understand and represent this space, I had to actually visit the land.

Prior to visiting True Blue, I found an article about the work this man named Jackie Whitmore was doing to care, protect, and maintain the several burial grounds on True Blue and neighboring plantations where our family was enslaved. I reached out to him, found out we were cousins and knew that this connection presented the opportunity to safely visit True Blue.

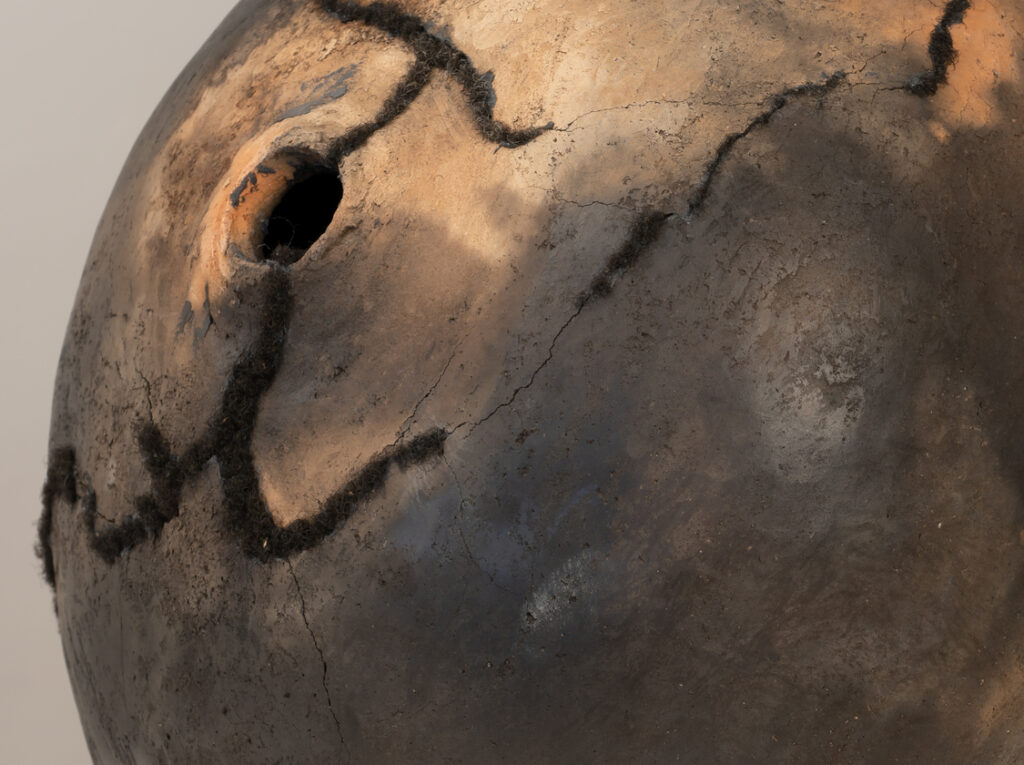

So in 2020, when the world shut down, I traveled to True Blue, met Jackie for the first time, and got a greater sense of the “place” in which my ancestors lived. This became the turning point in my practice and the transition from using materials that referenced the land, cotton, indigo, rice paper, archival documents, to using the land directly. That was the beginning of my transforming the soil from True Blue Cemetery into ceramic sculpture. During this visit, I also started collecting physical objects related to the structures my ancestors built on or near True Blue plantation.

These objects served as the physical evidence of their lives contrasted against the erasure of their lives and presence on the land. This trip laid the foundation for every single piece in the current exhibition.”

The journey of the exhibition is one thing but what about yours? Did Remains transform you in any way?

“This show has completely transformed me. It has shown me that my practice is actually ancestral work. I had a moment back in my studio in Philly when I was running my fingers through the soil and meditating on the fact that I am literally touching the ground that they were enslaved on. That their bodies are in this dirt and I am a descendant from this land. I was thinking about my deep responsibly to this material and the autonomy I have to shape this soil to any corner of my imagination, a privilege my ancestors did not have centuries ago.

This show deepened my sense of responsibility and, overall, increased the stakes for me. Another interesting thing that really transformed me about this work and show is that it gave me a place to channel my grief. Right before the 2020 trip, I experienced significant loss. My mother, grandfather, and Uncle died just months before the trip. I reflect a lot about how after experiencing so much loss I started working with soil from a cemetery. I think years from now I’ll look back at this show and see how important this work was to my career, practice, and personal life.”

Nearly every ingredient in this exhibition has some significance. Educate us about the materials used in some of your pieces.

“My practice is constantly considering the embedded histories within the materials I use in my work. In this show every single material or object used speaks to the complicated histories of slavery, commodification, ownership, and my own ancestry.

The pews in the show are the original church pews from Jerusalem church on True Blue Plantation. Made of oak wood, they were built by my emancipated ancestors c. 1890. The Church has currently been converted into a hunting club and is owned by the Winges family who are the descendants of the overseers of True Blue Plantation.

The Balcony Balusters are the Original balcony balusters of the McCord House in Columbia, SC. Built in 1849 for David and Luisa McCord by my ancestors from Lang Syne Plantation. Among the enslaved carpenters who built the home were John Spann and Anderson Keitt. The house is currently owned by Henry McMaster, the incumbent Governor of South Carolina, who purchased the property in May 2016. The house serves as student housing for University of South Carolina students.

The rest of the materials present in the ceramic and paper works are Indigo dye, red clay carrying blood, centuries if sweat, and decomposed bodies of my ancestors… Human Black hair collected throughout the diaspora, wills written by enslavers, cotton beaten into a pulp, Carolina gold rice that use to grow in True Blues environs.

All of these materials speak to or are the physical evidence of their labor, intellect, skill, expression, and lives.”

You mentioned that you met your family’s historian during the process of piecing together Remains. Was there anything glaring brought to light? In what ways did your knowledge of your family tree expand?

“In every way. Jackie Whitmire literally taught me about me. We traveled to over 8 locations through South Carolina that had a direct connection to my ancestors and lives as enslaved, emancipated, and self emancipated people. Jackie is literally the keeper of my ancestors. His knowledge and commitment to archiving, preserving, protecting, and maintaining the spaces connected to our family is incomparable. It’s his life’s work.

He even organized six historical markers to be placed at the burial grounds of our ancestors on various plantations and one at the McCord house to further protect those spaces. What I’ve learned the most from seeing Jackie’s work is that as long as I am doing my work about True Blue and Lang Syne plantation, my own practice needs to support Jackie’s and really be an extension of his own intentions and work with our ancestral land. “

This is your second solo exhibition with the gallery. How has it been working with Claire Oliver?

“My first solo exhibition was in 2020 right in the midst of COVID, so there were a lot of feelings attached to that day. My second time around, I feel like I’ve been really able to stretch myself and give a lot of time towards the work and the work alone. At this point Claire and I have our rhythm when it comes to installing the show. Claire will decide where the work goes, how to hang the pieces, what goes next to what and I’m just there to say, ‘Oh yes, I like that or just a little to the left.’

But from the beginning Claire’s strength has been in placing work. That’s her cache. With this show alone, Claire has been able to place the work in four museums. Having been exposed to art and art making in a serious way at the age of three taking art classes at the Newark Museum, it’s a true blessing to be in the collections of some of the best institutions in the country.”

We always inquire about the artist’s intentions. What are your intentions with Remains?

“I guess my intentions are in the title. Remains. This show is not only about the human remains that are buried beneath not only True Blue and Lang Syne Plantation grounds but this entire country.

In pockets all over America, Black and indigenous burial sites are at risk of being lost and unprotected simply because of whose bodies are buried in those spaces, and this is if the gravesites have not already been erased.

I hope this exhibition shows the various ways we could bring attention, protection, and reverence to these sites (burial grounds, plantations, universities built by the enslaved etc.) and the people who defined them under some of the most violent conditions in human history. I’ve found in my own work with True Blue and even my involvement in the exhibition Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina that was just at the Met and traveling to MFA Boston that most of the tangible things that remain and that speak to the lives of the enslaved are nearly fragments and that this erasure of an entire people is intentional, systematic, and violence realized.

The fact that centuries later we know more about minute details of the Slave master and significantly less about the slave is deliberate. It’s a way of denying the humanity of Black folks.

So, in this show when I hang what is left of the balcony baluster from the McCord House that’s been halfway devoured by termites, simply because it was made from the enslaved labor of my ancestor in 1849, that’s significant. Or when I install the church pews built by my family so they could express their spirituality and freedom steps away from the rice fields where they labored, that’s significant. All the things that remain today, that we could claim and touch and that point directly to these Black people’s lives are significant and worthy of care and protection.”

For the audience, what do you feel will be the most important takeaway?

“I don’t want to assume that I’ll know what each person will take away after seeing this show. But I do hope they walk away feeling that I put a lot of care into this work and that through my own practice my ancestors are loved and not forgotten.”

Remains is on display until March 11th at Claire Oliver Gallery (2288 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd.) Be sure to stop by and tell them that Quiet Lunch sent you!

Akeem is our founder. A writer, poet, curator and profuse sweater, he is responsible for the curatorial direction and overall voice of Quiet Lunch. The Bronx native has read at venues such as the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, KGB Bar, Lovecraft and SHAG–with works published in Palabra Luminosas and LiVE MAG13. He has also curated solo and group exhibitions at numerous galleries in Chelsea, Harlem, Bushwick and Lower Manhattan.