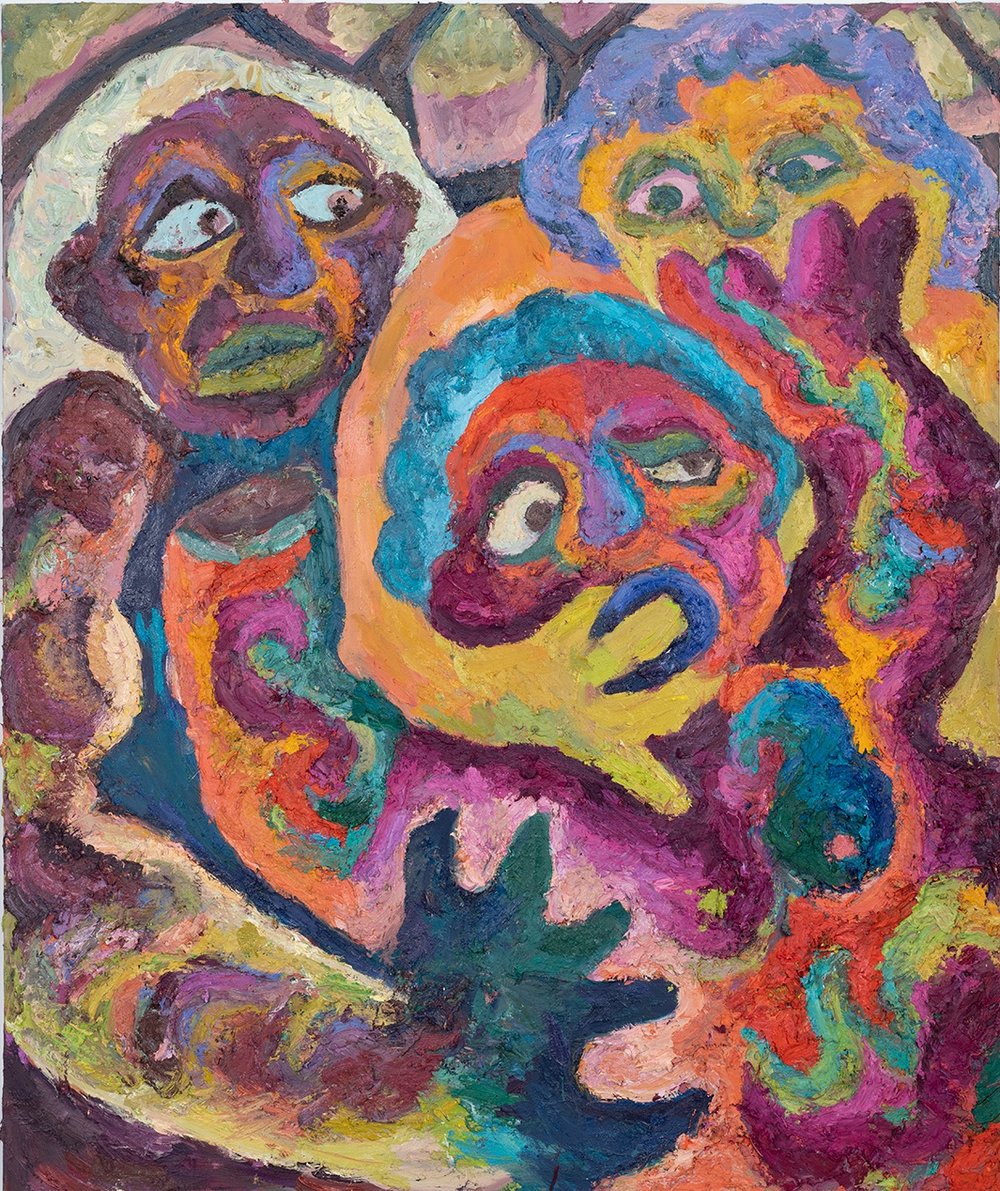

Ana Wieder-Blank’s recent solo exhibition ‘The Fairytale Protesters’ at Honey Ramka Gallery immersed viewers in a riotous intermingling of color and texture. Utilizing painting, ceramic sculpture, installation, and performance, the artist tackled issues of identity, sexual assault, marginalization, and women’s empowerment. We spoke with Ana about the inspiration behind her exhibition, her great love of creating alternate universes, and her plans for a sequel to “The Fairytale Protesters”.

1. Your work spans across multiple artistic disciplines — painting, sculpture, installation, etc. What do you find most exciting about delving into all these modalities, as opposed to just sticking with one concentration?

Installation has made it possible to create environments in three-dimensional space. This appeals to me as painter who works in a very textured way, it appeals to me as a sculptor, and mostly it appeals to me as a storyteller, somebody who is fascinated with creating theater in art. I often think of my work as a frozen climax of a play or a panel of a comic book.

Installation can create an immersive experience beyond what a single object can do. In this way the viewer is placed in the center of the action. This is designed to elicit an empathetic response to the viewer. I’m not interested in ironic detachment; I’m interested in the gut punch, with a hug and a laugh after. I have a dance and improv background as well, my experience with performance art feeds the installation’s impact. All the world’s a stage, right? If this is true than the viewer is more than the viewer, they are the players. Intellectual understanding of the thematic elements is important, but that comes after a visceral experience.

I also really love creating work in multiple mediums. Oil Paint satisfies me in a different way than clay, (though the two are highly related both intuitively and logically.) Printmaking satisfies me in a different way then performance or drawing. I think I’d get bored just doing one thing.

2. Can you tell me about the influence of mythology and fairytales within your work –what types of stories are you drawn to, and why? How does this material lend itself to commentary about today’s sociopolitical climate?

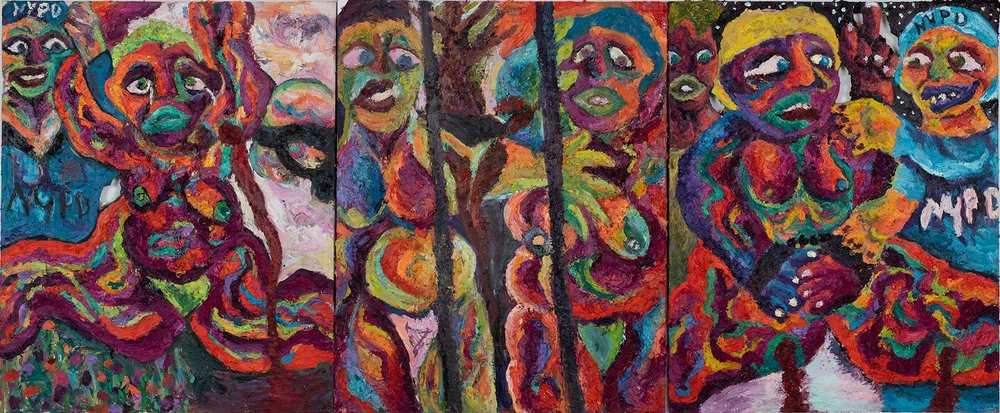

I describe my work as contemporary feminist political allegory. In my solo show The Fairytale Protesters the painting Badass Womyn (Dinah, Kali, and Persephone) Tear Down the Statues of Murderers and Rapists relates to both the events of Charlottesville in 2017 and to the recent synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh. Dinah’s Rape Trial Installation references the Kavanaugh hearings and the moving testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey-Ford. I work with narratives from the bible, Greek, Mexican and Indian Mythologies, and fairy tales. These stories are loaded with political, gender and sexual allegories that are as potent today as they ever were. I am particularly interested in narratives that deal with ideas of outsider marginalization, queer sexuality, environmental concerns and issues of rape and consent. I couple womyn characters together and explore dynamics of hidden and overt love, jealousy, and escape of patriarchy.

Unfortunately, many of the issues we’re dealing with as a culture today (rape, abuse, othering, environmental degradation etc.) have been around since the beginning of time. Mythology is both timeless and incredibly timely. It’s culturally specific but also universal, and a profoundly individual somatic experience. As somebody who is intensely involved in mythologies I always find more to mine. I’ve studied the works of Clarissa Pinkola Estes, Aviva Zornberg, Ahanra Pradesh, Jung, and Campbell, and they have taught me that themes, archetypes and storylines present themselves time and time again through various time periods, cultures, and geographic locations (Dinah and Persephone is the one I work with the most) Through these narratives I can express my thoughts and feelings about macrocosmic and microcosmic political and personal experiences with far more freedom then I would have working with factual news. I can extend the story past its end, loop it around and imagine new endings. I can couple characters up, kill them off, separate them, reunite them.

I used to write a lot of fiction and this way I get to use those talents and interests that siphoned off when I decided to focus on visual art. I’ve grown up with deep Jewish roots. My cultural tradition is all about telling stories. My childhood was all about telling stories. These characters are my friends. With them I’m never alone.

3. Your work centers around strong women who’ve suffered through great trauma, like Persephone and Dinah, recontextualized into alternate realities and storylines. What was your focus in retelling their stories? Can you walk us through the narrative playing out in “The Fairytale Protesters”?

In the Fairytale Protesters these characters (Dinah and Persephone are the protagonists but also Kali, Vashti, Demeter, Leah, Medusa and others) are taken out of their individual narratives. They protest the patriarchal culture in which they live. They are strangers in their narratives and their bodies; isolated by gender, belief systems, queer sexuality, untypical bodies. They are lesbians, trans, and genderqueer, fat and differently abled, mutilated, and heroic, bruised and bloodied in service of their cause. Together they are a powerhouse of protest; united by the things that isolated them.

Dinah and Persephone are present in almost every work in this exhibition. If they are not there, then their mothers are; Demeter and Leah. Dinah and Persephone, Kali and Vashti, Lilith, Eve, Hagar, Medusa, Hecate, Demeter and Leah are the fairytale protesters.

Sometimes I couple them up (like Dinah and Persephone, Lilith and Eve, and more.) This way they can begin to heal their respective traumas through their love. Together they protest the patriarchy, and together they dismantle it. All these characters (but particularly Dinah and Persephone) go through hell together. They deal with rape, abortion, police brutality, Nazis and more. They grow together, and they begin to create a new world together.

4. Much of “The Fairytale Protests” addresses this specific time in United States history, referencing polarizing moments such as the Charlottesville white nationalist march, the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, and the Kavanaugh hearings. What is it about remixing contemporary events with fictional characters that you find so fascinating?

I can give myself a lot more latitude to explore tricky, painful, problematic issues then I would have if I were making work directly about these events. I don’t have to stick to the facts. I can imagine these events turning out differently, turning out better. I can reference the news and history without being bound by it. I can imagine what would happen if just one factor was different, or if many factors were different. I’m also not trapped by the oppressive news cycle. I can extend the reach of these stories, characters, and themes into more universal territory while still being timely. Many of the characters are veiled self-portraits; one could make the argument that they all are. Ultimately, I can explore my own feelings about political and autobiographical events without making it directly about me. In addition to freedom, these characters also provide me with a veil of protection; without which I could not be so bold.

5. There is a boisterous, anti-establishment sensibility to your work, and coupled with your bold use of color, meaty texture of materials, and disproportionate renderings of your characters — it makes for a very striking statement. What response do you hope to elicit in a viewer when confronted with this raw, Maximalist aesthetic?

I hope to elicit a strong emotional response, followed by a thoughtful parsing of the themes present in the work. I hope to elicit empathy, anger on their (Dinah, Persephone, etc.) behalf. I hope to elicit catharsis, discomfort, tears, laughter, whatever is authentic to the viewer’s experience. I know my work is difficult, uncomfortable, demanding of an intense level of engagement. I understand why a lot of people love the work in a gallery but couldn’t live with it. But if you’ll stay with it, it will reward the effort (I hope) I understand that the narratives aren’t immediately accessible to most people (my work takes a lot of research and I don’t expect my viewers to do the same amount of research) but I always say I want the audience to land on the runway rather than on the river. By which I mean there are a lot of places to land on the runway. If they’re getting something (themes, emotional impact, relationships, anything really) I’ll be satisfied. I am always curious what people come up with on their own. It delights me when they are picking up what I’m laying down even if they don’t grasp the specifics. I’m trying to ask more questions about my viewers experiences.

6. You’ve done several shows with Honey Ramka Gallery in Brooklyn. How has your experience been collaborating with their team?

Jesse Patrick and Martin and Bryan Rogers are incredible. They each have different talents and personalities. Bryan is a genius at installation and making shows look their best. Jesse is a whiz at talking and writing about the work. In addition to their vast knowledge of= art and art history they are just genuinely kind people. They helped me move into my studio at Sharpe, have helped me maintain it. They go far and beyond the call of duty. Jesse even wheeled a three-foot sculpture across the Williamsburg Bridge with me. I met Bryan Rogers at Pratt (he was in my year in the MFA program) and Jesse shortly after. They have been my good friends for over 10 years.

7. Do you paint purely from imagination or do you make preparations beforehand?

I go through phases of making preparatory drawings. Lately I have been drawing before painting because the paintings are becoming more complicated. The number of figures and their movements are becoming more elaborate. However, the relationships between drawings and paintings are elusive. The painting never really looks like the drawing, nor do I expect it to. I’m thrilled when the paintings take an unexpected turn because it means I’m venturing into unexplored territory. It’s both terrifying and exhilarating. Sometimes I also make macquettes in clay.

8. You’re currently a Sharpe Walentas Studio Program Fellow, how has your experience been at their artist residency? During their annual DUMBO Open Studios event in April, what can we expect to see from you?

Sharpe Walentas is amazing. It took me seven years to get it, which speaks to the power of persistence. The studios are beautiful and the friendships I’ve made bring me a lot of joy. I do wish they did a little more structured community building activities like crit groups, studio visits with outsiders and more get togethers. Artists can be a little myopic in their studios and I always appreciate the push for more interaction. But it’s been a great year and I credit most of my current success and happiness to the fellowship.

As for open studios I’m hoping to reimagine some of the installation work I did at this show. I also have a lot of new work coming down the line and it’s a little more optimistic then the work at The Fairytale Protesters exhibition, which was very dark thematically (if not chromatically.) While The Fairytale Protesters Installation is by no means over; I’m also starting work on a sequel project; The Way We Would Live Installation. This project tracks the same characters after their successful revolution. Together they must create new governments, new ways of healing, new cultures. It’s hard work to create a feminist utopia. While there will be a lot of effort and struggle this new series is hopeful. I’m not done with anguish and trauma but there is also relief and joy and healing coming into the new work.

9. Anything else you’d like to add?

Thanks to everyone who came to The Fairytale Protesters. Come to Sharpe-Walentas Open Studios. April 27-29. And thanks to Honey Ramka for 5 magical years.