As a child, it didn’t feel like summer unless the streets were wet with water from illegally opened hydrants and the familiar jingle of the nearest Mr. Softee truck wafted through the air. Now, as an adult, it doesn’t feel like summer unless the streets run red with the blood of the unarmed poor and the cry of a grief-stricken mothers and wives batter my eardrums.

On July 5th at 12:35 a.m., thirty-five minutes after America just finished celebrating its independence, 37 year-old Alton Sterling was murdered by officers Howie Lake II and Blane Salamoni. How ironic, during a time when America is supposed to be celebrating and exalting freedom, liberation and, most of all, equality, people of color were immediately reminded that they are citizens of a country that has a history of depriving them of all three of those virtues. If one reminder wasn’t enough, the next day in Minnesota 32 year-old Philado Castile was shot and killed by an unnamed officer during a routine traffic stop. Of course, in both cases, the officers justified the killings. Alton was supposedly reaching for a gun while resisting arrest and Castile was thought to be reaching for a gun after admitting that he was carrying a firearm and reaching for his ID—per the officer’s request. The violence continued in Dallas on July 7th when Micah Xavier Johnson killed five police officers and injured nine others after a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest. He also injured two civilians.

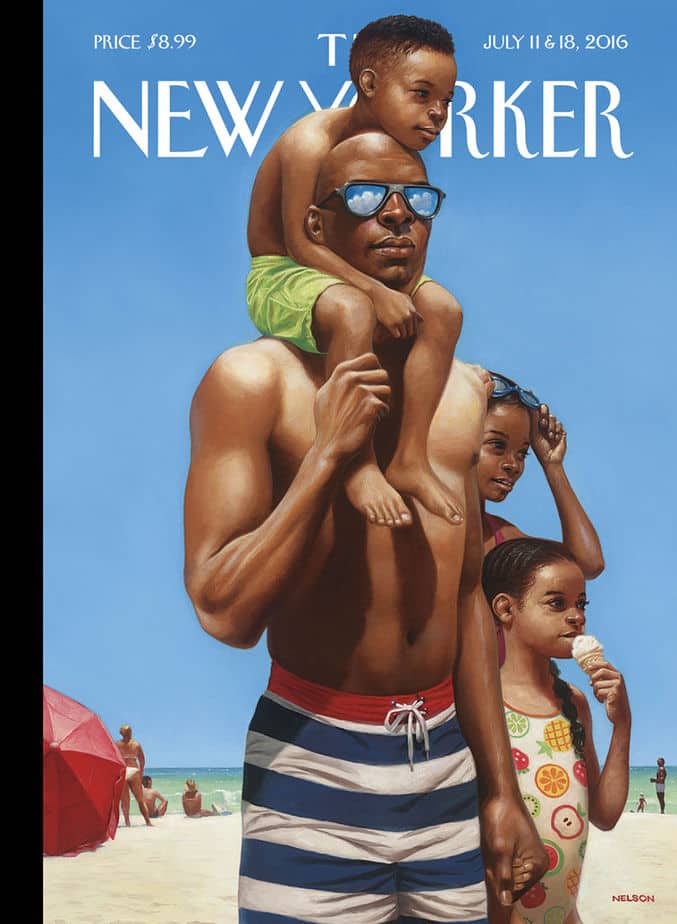

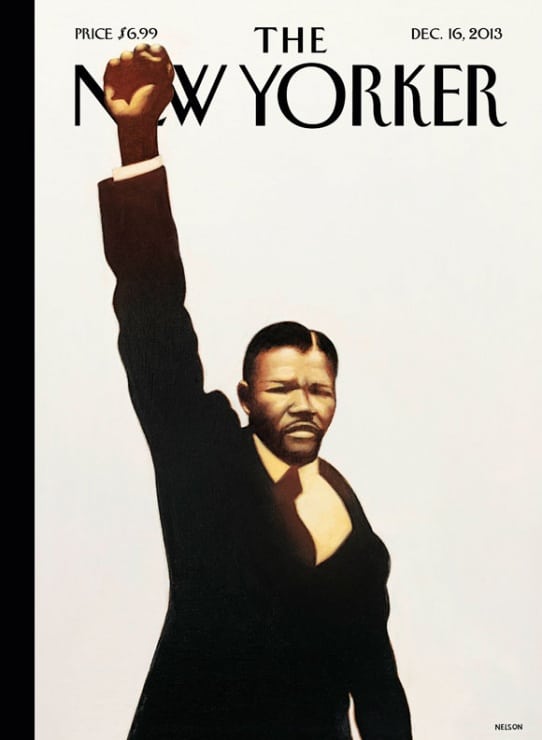

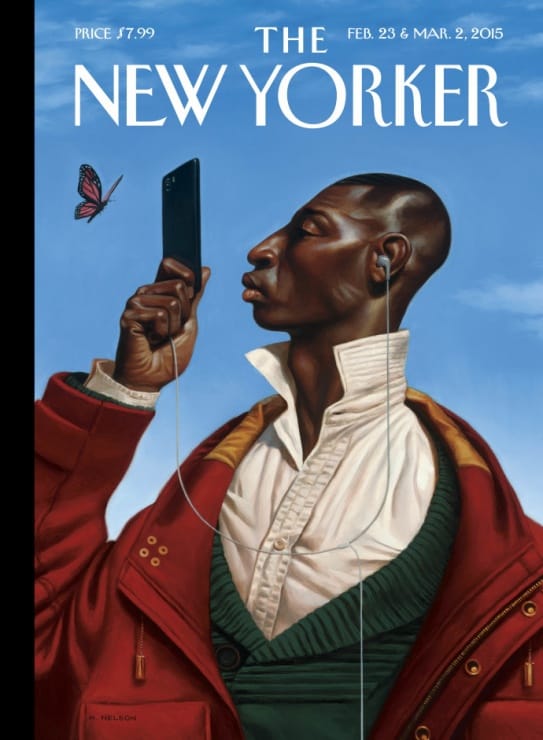

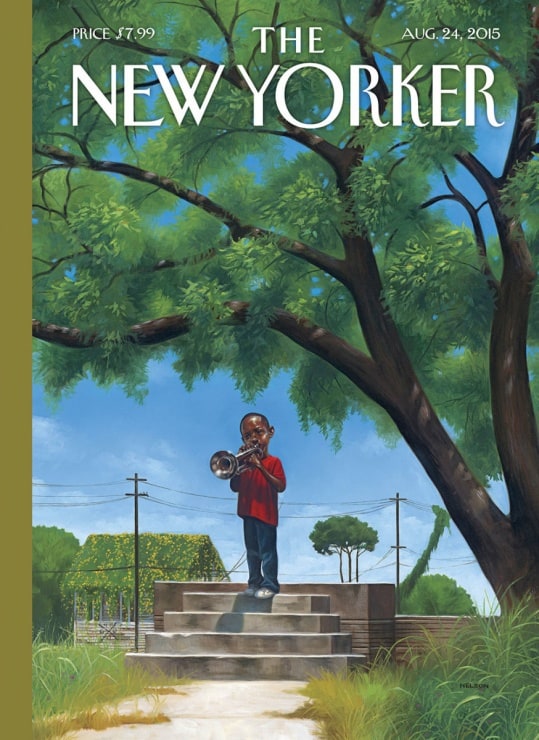

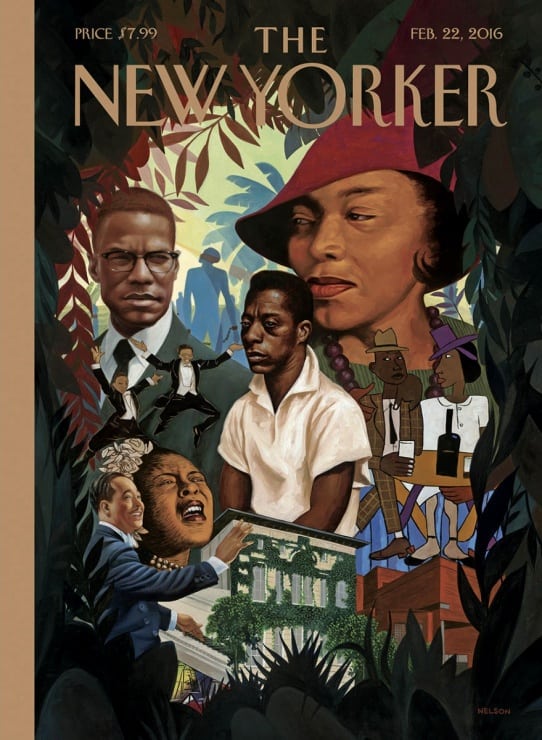

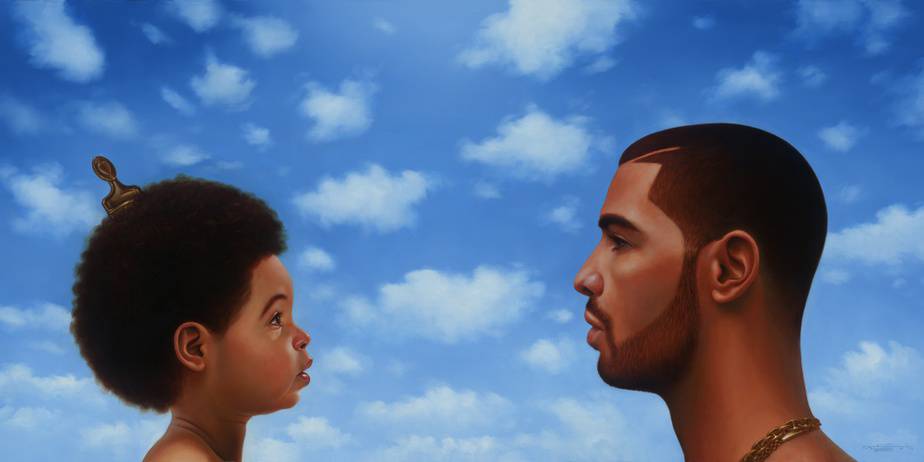

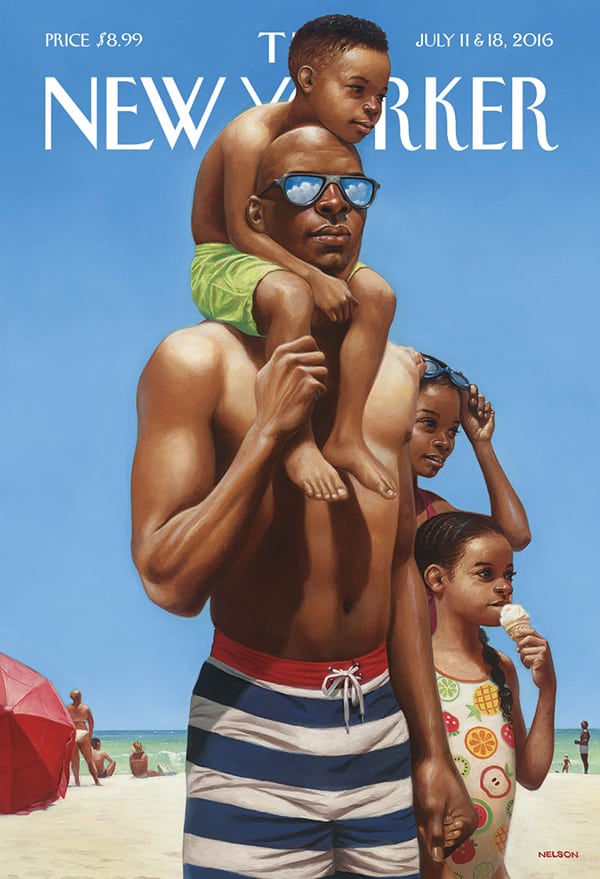

The week was turning out to be a bloody one as gun violence, poor police training and racial tension swirled together to create a tempest of tragedy. Then came “A Day at the Beach,” The New Yorker‘s latest cover by Kadir Nelson. Nelson, a Maryland native who grew up in Atlantic City, NJ and San Diego, CA, is a talented painter with a proclivity for creating vivid pieces that are rich in both aesthetic and cultural subject matter. A Pratt alumni, he has worked with The New Yorker in the past, having notched four beautiful covers under his belt. Nelson is also the artist behind the cover of Drake’s 2013 album Nothing Was the Same.

But this article isn’t really about Nelson or even The New Yorker. It is about the significance, the timing and the power of “A Day at the Beach.” Before making its official debut on newsstands, “A Day at the Beach” started popping up around the interwebs—particularly on Tumblr. Initially the piece came off as a strong, assertive jab against the stereotype that black fathers aren’t present in their children’s lives. Then the bodies started piling up and the cover took on a more poignant definition.

Being a black man, I have always known that this society thought of me as less than human; history has proven so and the present has been no different. Then again, the days of strange fruit hanging from the Poplar trees are supposedly long gone and our country has a black president, so people of color couldn’t possibly have it that bad, right? I would like to agree that we have made some stride but when black men and women are being slaughtered by trigger happy cowards with badges, it’s hard to not feel like we’re still—and always will be—at square one. We become convinced that in this country, a country in which all men are created equal, we are still only 3/5 of person.

“A Day at the Beach” by Kadir Nelson. | The New Yorker | July 11 & 18, 2016

The death of people of color by the hands of irresponsible, overzealous, poorly trained law enforcement isn’t anything new. Nonetheless, it isn’t the occurrence that is terrifying but the frequency that raises our hackles—that point where violence is no longer habitual but obsessive. We cannot go back to obsessive. We are barely coping with habitual. We can no longer bear with being expendable. We can no longer afford to be seen as a collective of thugs and welfare queens. We need America to know that we are more than that; then maybe they would care. This is what makes “A Day at the Beach” so vital. It depicts a black man not as a criminal, a victim, an athlete or an entertainer but as a proud family man.

This may not be a favorable comparison for some but it’s akin to what Bill Cosby did in the 1980s with The Cosby Show, where he transformed the visual of the black experience into something that is more than poverty and struggle. A well-off African American family living in a Brooklyn brownstone during a decade in which crack cocaine was ravaging black communities everywhere didn’t seem that realistic at the time but in retrospect it counteracted other negative aspects of the black condition; negative aspects that were plastered throughout the media, broad-brushing people of color and placing them in an unsavory light. It also bestowed upon the Black community a sense of hope and motivation. The same could be said for other sitcoms that followed such as Family Matters and Fresh Prince of Bel-Air or Living Single and Girlfriends—where black women were depicted as career women, entrepreneurs and creatives rather than overwhelmed single mothers, sassy sexpots or helpful servants.

Strangely, with the exception of the new arrival Black-ish, shows and images depicting the other side of the Black condition have been cancelled and all but erased from the media today. The need to project a positive and accurate image of Black America is more necessary now than it was thirty years back and that is an unflinching shame. In a way, “A Day at the Beach” helps shift the paradigm. It isn’t the most prolific piece of artwork of the 21st century but it still resonates with great relevancy. For America, this cover should help them see us as human beings—Americans, deserving of the very same rights and liberties that this country was founded on.

Akeem is our founder. A writer, poet, curator and profuse sweater, he is responsible for the curatorial direction and overall voice of Quiet Lunch. The Bronx native has read at venues such as the Nuyorican Poets Cafe, KGB Bar, Lovecraft and SHAG–with works published in Palabra Luminosas and LiVE MAG13. He has also curated solo and group exhibitions at numerous galleries in Chelsea, Harlem, Bushwick and Lower Manhattan.