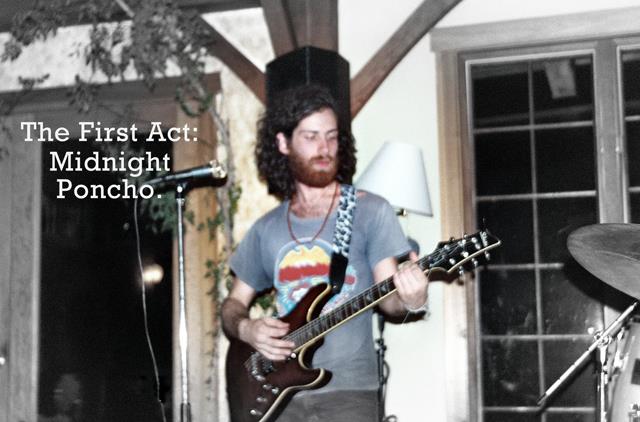

On the night of December 21st, while most were preparing for the end of time, I was driving to rural Connecticut for a solstice gathering at the home of Midnight Poncho. After a long journey on various obscure county roads, I arrived at the home base of Luke Benjamin, the main man behind Midnight Poncho.

- Photo by Matia Gaurdabascio.

Armed with my camera, voice recorder, and a bottle of Jameson for the host, I was welcomed into the intimate circle of friends who surround Luke and contribute in various ways to the Midnight Poncho music act. Luke’s music came to my attention when friend and contributor, Lawrence Martinez, wrote to me at the magazine and recommended that I listen to Midnight Poncho.

I listened. And I loved.

Luke’s musicianship is, without question, highly acute. His music, which for ease of description falls under the “folk” category, is far more intricate than mere genre classifications can qualify. His music is deeply rooted in nature and in many ways, the sound itself produces a spiritual, even visceral, experience. Nowhere is this more apparent than on the album, Samsara.

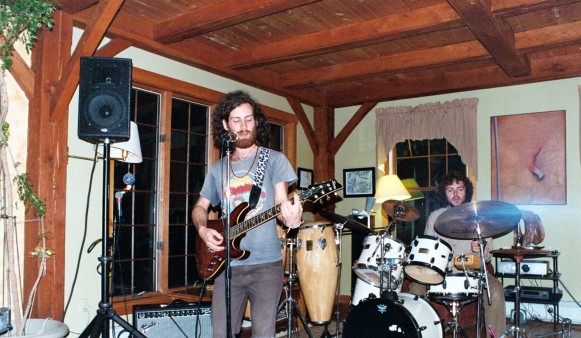

Photo Courtesy of Lawrence Martinez.

At his home in rural Connecticut, Luke, his friends and I had a lengthy discussion about his music, the music industry as whole, and about the spirituality that flows through him and into his music. Songs like “The Deer and the Dancing End” illustrate scenes from nature that the human perspective rarely perceives, or takes time to notice. When I listen to Luke’s music, I can’t help but let it take me over, as though I have suddenly been possessed by Mother Nature herself.

While the rest of the world was waiting for some brutal end on the night of the 21st, Midnight Poncho and I shared an evening that celebrated life and the saving grace of music. I am most grateful to them for opening their doors to me and letting me into their world. Luke–wherever you are–thank you.

And now, with the greatest pleasure, I give you, dear readers, Midnight Poncho. Below you will find an original video of Midnight Poncho by Lawrence Martinez and two songs that moved me ever so much. Given the length of our interview I am abandoning the typical format of this column and instead including the section of our interview that I feel will best recreate the evening of our gathering and give you a taste of Midnight Poncho in his truest element. I hope you all find as much enjoyment from his music as I have. Cheers.

————————————————————–

————————————————————–

————————————————————–

Photo by Matia Guardabascio.

[Contributing members of Midnight Poncho: Luke Benjamin, Connor Effenberger, Tyler Christie, Lawrence Martinez]

MATIA: We were just talking about the music industry, bandcamp, the idea of making money off of your music and charging for it.

LUKE: I was talking about how… I think it was a year ago and you [Tyler] and Connor were here and we had that conversation about how, you know, I don’t want to make the effort to get my music out there. And you guys were like, people would like it!

CONNOR: I mean you gotta throw the bait out there.

LAWRENCE: I think it seems like there’s a lot of people who make music, who just spend an incredible amount of time making music, but don’t spend time doing self-promotion, so I think if you want to live off your music, then you have to do that.

LUKE: That was the thing. I always liked the idea of making music, but it never seemed feasible to make a living off of it. It’s not that I didn’t want it to happen, it just seemed so out of the question. It was hard to imagine it, so I didn’t want to make the effort. I think deep down, that was the focus of this music project. I was just going to make it and give it to my friends and if they like it maybe they’ll tell someone.

TYLER: I didn’t know that… that I was working for you!

[Laughing]

LUKE: Eventually you’ll get paid… if you make me some money!

[Laughing]

MATIA: Do you all contribute to Midnight Poncho… everybody here?

CONNOR: In one way or another.

LUKE: Yeah, in one way or another. Jamie was my roommate in college. The first Midnight Poncho song ever written was from Jamie’s perspective. You’ve never heard it [to me] because it’s not on the internet, but it’s a song called, “I Want to See”–I’ll burn a disc for you [to me]–and it was very much inspired by this man right here [gesturing towards Jamie]. He was a little unhappy at one point and I felt it and I wrote a song about. And I played it in our room and everyone’s like, ‘Oh my god that’s so good,’ and I was like, ‘Really?’

LAWRENCE: It’s interesting too because all the people here have been spread across different places and I think that music does a really good job of binding this group of people together and everyone’s different projects.

LUKE: Someone sent me a music video of a bunch of people in a room singing, “I Want to See,” and I was like, “What?!” It didn’t make sense to me that someone else was singing a song that I wrote, that I’d never met. It was like… you can’t cover a song that no one’s ever heard! It was weird.

[Laughing]

Photo by Matia Guardabascio.

CONNOR: Even from friends that I have that don’t know you [to Luke], they’ll listen to you and they’ll consider the music to be, you know, it’s above-average, it’s above-par, it’s exceptional music. They find it funny that it’s just this esoteric, weird, like ‘who knows where the fuck this came from’ music. And it’s a mystery too because it’s like, when’s the next thing coming out? I don’t know. Is there any plan? I don’t know.

LUKE: Yeah, at Music is the Medicine, it was one of the few times that someone came up to me that I’d never seen before and they’re like, “Dude, are you Midnight Poncho?” And I’m like, “Uh, yeah.” And he’s like, “I love you.”

[Lots and lots of laughing]

MATIA: Back to the music industry… Luke and I were talking a bit about it before and I told him about this thing that my Dad says… my Dad’s a musician as well. He was in a band in the 80’s and he says that in the music industry these days, ‘you can’t make a living, you can only make a killing.’ If you want to actually make music into something that you can turn into a viable income, you have to make a lot of money. There’s almost no way to do it as a job, like someone who gets up everyday, takes the train to their office and works all day.

LUKE: And you almost always have to screw somebody over, or take advantage of them. It’s a very selfish thing. I’ve just always equated… I was in a band growing up and we were very self-promoting and my friend, who taught me how to play guitar; he’s the greatest drummer I’ve ever heard. His dad is the drummer for Megadeath. He started playing drums when he was like 2 years old. He’s an amazing musician and he’s like, ‘this is the only thing I can do in life, so I might as well make a living at it.’ We made music together in high school and then we kind of… he went to L.A. to try to become a studio drummer, and I went further and further into abstraction. He’s doing this and I’m doing… I don’t know what that is.

[Laughing]

LUKE: We were very self-promoting back then. When I got out of that phase of just automatically self-promoting yourself, I took a step back and it just felt very much like prostitution to me, like, ‘Look at me! I’m cool.’ But I found you can promote your music without being a prostitute.

CONNOR: We were like… we offered to pay you [to Luke] to record your music and you were like, ‘I’m not your whore.’

[Laughing]

LUKE: But I’ve come to realize that it’s possible to self-promote yourself without self… prostitutizing. What’s the word?

LAWRENCE: Compromising your moral compass…

MATIA: That’s very poetic.

[Laughing]

MATIA: Well sites like bandcamp and soundcloud make it possible for you to subvert that whole thing. And I feel it’s growing a lot more lately. One could even call it a revolution against the industry.

LAWRENCE: That’s also something that I think Redding Hunter is super on top of.

MATIA: Yeah, he was talking about how he doesn’t do the whole label thing in his interview with me. And how, you know, there’s a kind of lack of integrity in the whole thing and you have to sacrifice a part of your expression in order to accommodate these labels.

LAWRENCE: And then also too, if you’re involved in that path as means of income, then it’s a work that is not intuitive, or you can’t make things based on feeling. You have to make things based on deadline. Even if you’re playing around all the time, then you have to go do it.

LUKE: That was the one thing that was like in my mind every time time I’ve written a song. I remember one day I woke up and was like, ‘Oh there’s a song in my head,’ and I sat right there and just flushed it out til it came out and then recorded it that day. And under any other circumstances it wouldn’t have come out, like if I had been like, ‘Oh my boss really needs me to write a song,’ and sat there all like, ‘Paycheck!’ That’s the antithesis of the way I make music.

LAWRENCE: Yeah, and so few people know about it. I mean, the people that listen to Midnight Poncho are some people we don’t know, but for the most part it’s everyone in this room tonight.

LUKE: Lawrence emailed some people at Microphone in the Trees, which is a blog, and got them to post some music up there.

LAWRENCE: It was the same day too. And they were really psyched. And I think that’s the response you get from this music. It’s good music.

MATIA: Why do you think people feel that way?

LAWRENCE: Just because it’s honest. I think a lot of time, especially with folk music, my opinion is that… I think that if you listen to Luke’s songs, it comes through. I think there is a sincerity to his music because it’s very real versus like… I mean there’s a lot of people who make remarkable music, but sincerity is hard to find. And I feel that a lot when I listen to things like Luke’s music or Peter and the Wolf, Dana Falconberry… all this stuff just has a really unique kind of category.

LUKE: It’s a very elusive category. There’s categories of music and then there’s categories of expression in the music. These people are expressing their music, not necessarily through the sound, but through how they go about doing it.

MATIA: How they go about doing it, as in the process of making the music?

LUKE: Yeah. It starts with writing a song. I think there is a distinction between how people write songs. And that goes into a very long and intellectual conversation that I’m not sure this is the appropriate time for, but you either write a song for an audience or you write it for yourself. When people write songs–and it’s the same with poetry or any type of writing–essentially I think of song as an extension of poetry… You either write it thinking, ‘I’m writing this and someone is going to hear it and enjoy it.’ The way I think about it is that I don’t write any of the words, I find the words. All that stuff exists in potential or possibility and when you catch it, it’s not anything that has to do with you, it’s a non-human voice or a non-personal voice. And so, you capture that and express it and it doesn’t actually have anything to do with you, whereas people that are writing songs that is meant to please people… it’s not that clear of a distinction, but there are gradients of that.

For me, I’m like the opposite end of the spectrum. I’m not writing this for other people. I’m writing it for a voice that’s coming to me and I’m trying to respect that voice. And I think that’s a difference that a lot of popular musicians that are looking to make a living off of it, are trying to create music that appeases people, or they’re writing things in their head with other people’s opinions in mind. Which isn’t… I mean people make amazing music doing that. I’m not trying to knock it; it’s just two different ways of doing it.

MATIA: The voice that comes out in the album, Samsara, is deeply, deeply rooted in nature…

LUKE: Yeah, deeply non-human. Some of those songs, I don’t know where they came from. That was like… that album was… one friend expressed to me that, that album was one “deepecology”. The basic principle of that being non-human voices, or humans picking up on non-human voices and speaking for them because they can’t speak in the human realm. And that was my goal, to write a song where I wasn’t thinking about humans, I was thinking about animals and what might go on in their realm… but it might. And one really good song that wasn’t on Samsara, it was on Songs for Gaia, “Old Blind Crow Magic Healer” was like… I just recorded that one day. I don’t think I wrote it. It was just there. I just started playing guitar and singing and that came out. I don’t physically remember writing it; it just appeared. And I think some of my best songs come from that… when I’m not paying attention to me, I’m paying attention to a voice that isn’t me.

MATIA: Well, it’s a part of you at any rate. It wouldn’t come out of you if it wasn’t.

LUKE: That’s a funny distinction right there. I guess it just depends on how you think about it. I don’t think about it as coming from inside myself, but it came out of me…

CONNOR: From something else, like you’re the receiver, just spitting it out.

LUKE: But that’s a profound feeling I have about poetry and expression through words is that you’re the muse, you’re not speaking your words…

CONNOR: You’re not the creator…

LUKE: Yeah. You’re picking up on something and expressing it through the words that occur in your mind. There’s an unknown that you sometimes have to tap into and speak for and the biggest part of it is that it isn’t a known, it’s a mystery and that’s what you want to pay respect to and sing about.

Photo by Matia Guardabascio.

****If you know a band who you think would be a good fit for this column, then please contact Matia Guardabascio at info@quietlunch.com.****

Written by Matia A Guardabascio.↓

Matia A. Guardabascio: (n.) editor at large; a silly, dirty old poet known for her enthusiasm, her exuberance and her contradictory opinions of mankind.

Matia Guardabascio is a proud citizen of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and a graduate of Rutgers University with a degree in both English and French Literature. As the daughter of a musician and a school teacher, Matia grew up in a musical household with parents who made a concerted effort to instill in her the value and importance of the arts. She is a music enthusiast, an avid reader, a writer of prose and poetry, a traveler, and an enthusiastic imbiber of red wine. The piano is her favorite instrument, followed by the drums, and she loves Impressionist artwork, especially because she doesn’t need to wear her glasses to see what’s going on. That’s right, the glasses are not for show. She wears tri-focals because she reads too much, or as her good friends might say, she actually 80-years-old.