For fifty years we have been grappling with what the word “feminism” means. Somewhere between the appearance of two American films—both about nannies— one a sing-along children’s blockbuster created in 1963 and the other a cult documentary for the small screen released in 2013, every citizen of the world had to swallow at least one working definition of this problematic word that we were promised was good for us—whether we wanted to or not.

Both the smiling, levitating imaginary caretaker-for-hire of Mary Poppins (1964) and the secretive, hoarding, nanny-artist of Finding Vivian Maier (2013) fed unpleasantness to children, the former with sugar coating and the latter with misanthropic force.

Both the smiling, levitating imaginary caretaker-for-hire of Mary Poppins (1964) and the secretive, hoarding, nanny-artist of Finding Vivian Maier (2013) fed unpleasantness to children, the former with sugar coating and the latter with misanthropic force.

The show “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” that closed at White Box the same day as the various iterations of the Women’s March around the world, presented yet another healthy dose of post-Grrrl feminist nutrition. The invented, playful 34-letter word is from the sixties Disney film starring Julie Andrews. Breaking down the various parts of the clever, nonsensical song lyric, Lara Pan and her co-curator Ruben Natal-San Miguel came up with “atoning for educability through delicate beauty” as a new meaning for this silly word and hence, the unifying theme of this powerful show. Their act of fake poststructural linguistics bringing new meaning to an old quest—one that pre-dates Mary Poppins by centuries, in fact—perhaps intentionally undermining the seriousness of big questions being asked: How shall a woman present herself in the eyes of a patriarchal society? By tearing down social constructs that sideline women, can an exhibition empower women and condemn a few of the many conventions unjustly imposed by society worldwide?

The artists in this exhibition spanned various gender identifications, national origins, generations, and artistic mediums.

Three important female artists known to me, only because they were each part of Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondence School, a way of engaging one’s fellow communicators way before the age of social networking, were each represented here.

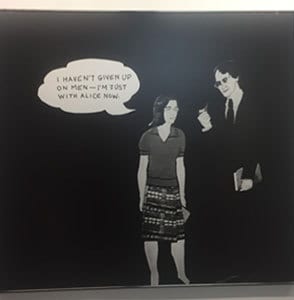

Eleanor Antin’s 1978 work, Rosie and the Professor, was featured as one entered the space and though it was labeled as a “Vintage Photograph,” the crudely rendered black and white graphic image foreshadowed both computer generated pictures and hand drawn “graphic novels” with an Old School comic book speech bubble stating, “I haven’t given up on men. I’m just with Alice now.” Antin, who combined performance art and mail art with her postcard series “100 Boots” said in a 2009 interview, “I was fortunate that I grew up as an artist at a time when all the barriers were falling down. It was a time of invention and discovery. I was lucky.”

Rose Hartman’s portraiture of celebrities at Studio 54 in the ‘70s and elsewhere has made this photographer as powerful and fierce a Style-ista as her iconic subjects, many, but not all, from the fashion world at a time when mostly only women cared. An 11 x 14 inch color print of Grace Jones in the 1990s, one from a numbered edition of 10, depicted her subject’s unstoppable style and assault on gender with visual acuity.

Rose Hartman’s portraiture of celebrities at Studio 54 in the ‘70s and elsewhere has made this photographer as powerful and fierce a Style-ista as her iconic subjects, many, but not all, from the fashion world at a time when mostly only women cared. An 11 x 14 inch color print of Grace Jones in the 1990s, one from a numbered edition of 10, depicted her subject’s unstoppable style and assault on gender with visual acuity.

An untitled self-portrait by Brigid Berlin of Warhol Factory fame demonstrated and understated the attitude of that era in which “superstars” flaunted their own underdeveloped personnas the way Cindy Sherman later self-consciously developed imagined characters and the way others like Nan Goldin stripped bare their own raw scenes in the name of documentation.

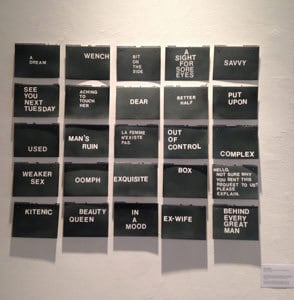

Nearby, Betty Tompkins’ Women’s Words 2016, consisted of 25 white on black painted notebook pages hung in an array which stands in stark contrast to her more well-known photorealistic, super-close imagery of men and women body parts, hetero and homosexual, engaged in intimate acts. Replacing her requisite pictorial jolts, Tomkins used understated but loaded word combinations: “behind every great man”… “ex-wife”… “beauty queen”…”better half”… “weaker sex”… and “used”… jumped out at me.

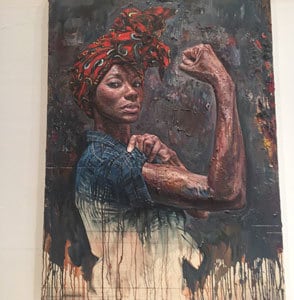

Tim Okamura’s 2016 oil on canvas, Rosie #1 (presumably no relation to Rosie and the Professor, or Rose Hartman?) invoked a modern, multi-culti version of the famous WWII riveter of the title. From rich, thick paint at the top to almost none at the bottom— but emerging from a field of drips—also surfaced a black woman with covered hair, rolling up her sleeve to reveal her flexing her muscle in the timely pose.

Tim Okamura’s 2016 oil on canvas, Rosie #1 (presumably no relation to Rosie and the Professor, or Rose Hartman?) invoked a modern, multi-culti version of the famous WWII riveter of the title. From rich, thick paint at the top to almost none at the bottom— but emerging from a field of drips—also surfaced a black woman with covered hair, rolling up her sleeve to reveal her flexing her muscle in the timely pose.

Marina Markovic’s 4:10 minute video, The Void, was my favorite of several videos in the show, an ultrasound of an empty uterus circumnavigating “mandatory” mores and tasks for females, raising issues of free will vs. imagined and real victimization. A voiceover by the mother, grandmother and great grandmother, of this Belgrade, Serbia artist who has exhibited internationally since 2006, was poignantly ironic as a subtitled and tortured litany of expectations. Other videos were by Sarah Singh, Meghan Boody, and Tania Brugera, an installation and performance artist who ran as a candidate for president in Cuba.

Agnes Thurauer gained notoreity when she changed Louise into Louis Bourgeois. Here, in Original World #2, a 2008 oil on canvas, this French-Swiss multi-media artist feminized male artist names and overlaid, pun intended, on Gustave Courbet’s 1866 oil on canvas The Origin of the World emblazoned with familiar names made even more familiar by turning he’s into imaginary she’s.

Genesis P-Orridge Breyer, another veteran of the pre-computer social networking mailstream, actually combined two 2003 works for this show, a transgender Jesus flanked by by 6 framed photos on each side called Stations ov Thee Cross. The admirable P-Orridge’s decades of cock blocking shock value, lands here in yet another of his-her-their “total war with culture… with all the things that one should be at war with…” and evidence of having gone under the knife to prove it. More at war with the self, a contrast was created with the subtle power and dignity of the famous Lange and Arbus photos situated right next to the array in the gallery.

Familiar images by Dorothea Lange, the depression era photographer who died in 1965 at age 70 and Diane Arbus who suicided in 1961, haunted our current political maelstrom with sobering drive-by iconography of our culture in a state of constant readjustment. Also represented across the room was Alice Austen—the first woman on Staten Island to own a car—by three more upbeat photos from 1905, 1897, 1895 respectively, including self-portraits.

Finally, a photo of a female toward the front of the gallery space by co-curator Ruben Natal-San Miguel rounded out the many photographic works that balanced and enhanced the presence of so many powerful video works.

Meanwhile, P-orridge-Breyer’s Jesus-centric installation also contrasted with the Islamist vibe across the room provided by Qinza Najm and Bolo, creating a missing take on feminism from Judaism. Not that one is required, but it might have made a nice triangulation with references to two other of the world’s major religions so prominent.

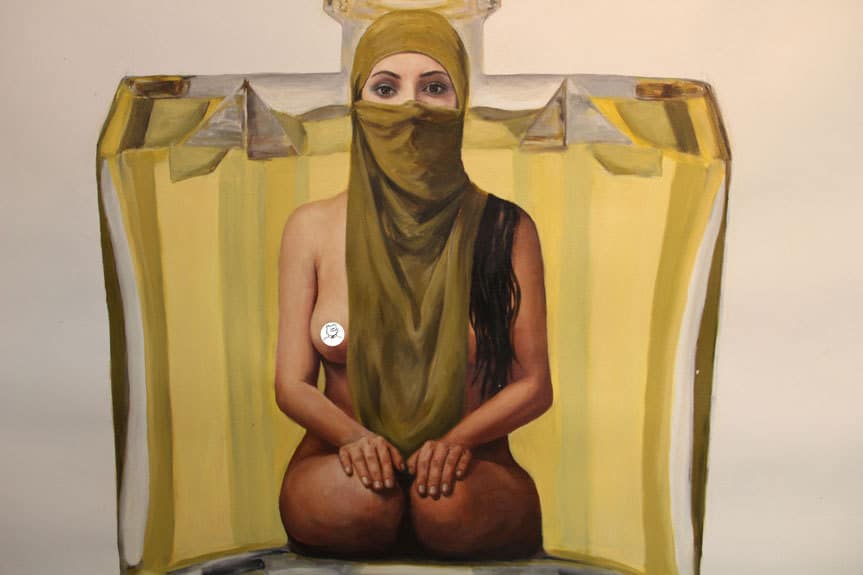

Norms, histories and traditions make a definitive exhibition on the deep topic of feminism difficult from all angles, including religion. But one such person who tackled it admirably, wajs Qinza Najm putting topical ideas into play against a backdrop of menacing male dominance.

Najm offered a provocative painting with video accompaniment juxtaposing the attractive images of a naked female body, a veiled face and a giant, reflective perfume bottle to create a push-pull exotic dance and simultaneous cat-mouse game of cautious seduction. It also juggled some lush, occasionally flawed but always very human brush strokes with the crisp sting of reality provided by a digital video player hanging on the wall nearby piercing the gallery space with headphones inviting the viewer to absorb the latest theater of war in the battle of the sexes.

If one succumbed, the video told the tales of three women: Amina, Qandeel and Ghandeer which accentuated the conflict buried beneath the layers of the fleshy painted visage.

Amina, an 18 year old Tunisian, whose topless image appeared on Facebook in 2013, to call attention to her patriarchal society, was sentenced to death by stoning and was told “I will throw acid on your face.” Her reply was, “My body belongs to me.” Qandeel, like Najm, a Pakistani, was nationally famous for her provocative but anonymous selfies, until her real name was revealed by a local journalist who later said, “I wish I hadn’t done it.” She was strangled in her sleep by her own brother to end her family’s shame. According to the video, “Soon afterwards an anti-honor-killing bill was passed… Waseem… has to be tried for the murder of Qandeel.” Ghandeer, an Egyptian 18 year old, dared to dance privately in 2009 with her girlfriends but when the phone video went viral, she became internationally hated. Her response, after posting it on her own Facebook page was, “My body is not a source of shame.”

“The videos are part of the story the perfume bottle is telling and it’s together one piece,” said Najm, demonstrating the necessity of a change away from patriarchal society when she explained, “the videos are footage taken from different channels that tell stories of oppression” and took a stand against “inept social and cultural practices.” Najm has contorted and distorted bodies against perfume bottles before, using advertising images appropriated from the Internet to underscore stereotypes of what women are supposed to look like and skewer anything that smacks of discrimination.

“I have been working on this female theme for three years now,” she says of her piece called “Niqabi Virgin,” the enticing 5 x 5 feet oil on canvas painting. The terms niqab and burqa are often incorrectly used interchangeably; a niqab covers the face as one part of a hijab while a burqa covers the whole body from the top of the head to the ground. It is worn by some Muslim women in public areas in the Arabian Peninsula, in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, the Palestinian territories, southern Iran and the United Arab Emirates as well as Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.

In a previous performance art piece, where Najm wore full hijab, she took selfies with others and posted them online using the hashtag #DamnILookGood. The piece was done in a collaboration with another Pakistani artist, Saks Afridi, a partnership collectively called “Bolo.” Their piece was about tolerance, liberation and challenging perceptions of women who wear hijab by choice. “I have never worn it personally except for my hijab piece performance,” Najm said. “No one in my immediate or extended family wears it and none of my friends wear it. It is mostly worn in the villages and smaller town and more conservative areas.”

Still, Qinza Najm proudly identifies as a Pakistani-American. “I am trying to tell through my personal story and by stories of other females who are survivors and not victims of their circumstances… females who found the courage to ‘speak up’ and change the stories of their life and become inspirations for other women and people.”

Many Muslim women who wear the niqab in the United States of America refer to themselves as a niqabi.

The other work Najm had in this show was a sculpture featuring a masked inflatable sex toy in full vestiary, executed precisely with Saks Afridi as part of their Bolo collaboration. The “Groom Hunter” was a satirical take on “the quintessential suitable girl every South Asian man and his mother wants.” She is “a stunning, subservient and appropriately educated girl.” She is a manifestation of “first world problems in a third world society,” all “told through the character of a blow up doll” armed with a machine gun and an extra chair. “This unreal object lodged in reality tackles… age-old societal pressures of contemporary global societies.” Finally, she is “achieving a sense of belonging while being out of place, finding happiness in a state of temporary permanence, and re-contextualizing existing historical and cultural narratives with the contemporary.”

The artists in this show created a dialogue about “improving living conditions and increasing autonomy for women” through “targeted economic, educational, and health initiatives.” It created familiar and unexpected hints of how feminism is remodeling itself in the 21st century, perfect food for thought in a rapidly changing political atmosphere. Like Islamic scholars that do not agree on whether veils are now obligatory, recommended or simply cultural, today’s feminists, whether female, male or something else, straddle a full spectrum of possible opinions stretching from atoning to unapologetic delicate beauty to radical educability.

Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious

December 9, 2016 – January 21, 2017

Curated by Lara Pan. | Co-curated by Ruben Natal-San Miguel.

Mark Bloch is an author and multi-media artist living in Manhattan. NYU’s

Fales Library houses an archive of many of Bloch’s papers including a vast

collection of mail art and related ephemera in its Downtown Collection. In

addition to his work as a writer and performance artist, he has also

worked as a videographer and graphic designer for ABCNews.com, The New York Times, Rolling Stone and elsewhere. He can be reached at

bloch.mark@gmail.com and PO Box 1500 NYC 10009. → Click here for more. ←