Whenever the West is influenced by art from beyond its borders, it’s anyone’s guess how much that cultural exchange is recognized. In some cases, like Kurosawa’s influence on American filmmakers, the answer is ‘widely’. In other cases, like the influence of the Bhagavad Gita on Emerson and Whitman (and by extension on American literature as a whole), the inheritance is buried under layers of history.

The debt that the West owes to Osamu Tezuka, though, lies somewhere in between. Japanese manga artists refer to him as “Manga-no-Kami Sama” or “the God of Manga”. Western animators and comics professionals know his name well. Still, even though many in the West know Tezuka, they don’t always know how largely his influence looms. While his two consecutive Eisner Award wins for his Buddha series have done a bit to change that, English-speaking readers have yet to absorb the incredible diversity, scope and range of his body of work.

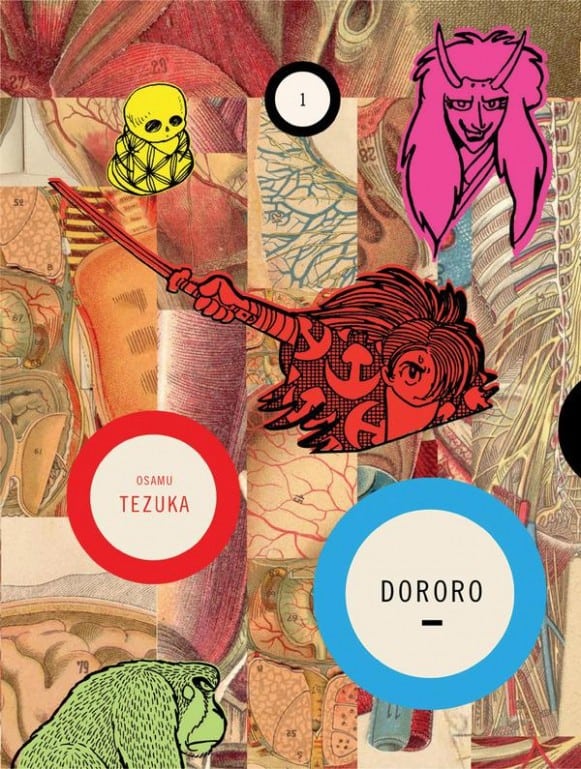

Dororo, a fantasy-horror samurai epic, is a great place for them to start. While the series’ premise requires some gymnastic feats of suspending disbelief, the payoff is creepy, fun and thrilling. Set in Japan’s Warring States period, the story is of a wandering young swordsman named Hyakkimaru whose aristocratic father offered forty-eight of his unborn child’s body parts to the same number of demons in exchange for power. The result of his father’s pact is the birth of an eerie, slug-like child who is set floating down a river by his heartbroken mother.

However, baby Hyakkimaru is given two strokes of life-saving luck. Not only is he born with psychic power that sustains his bodily functions, but he’s found and adopted by a folk doctor who uses his knowledge of alchemy, medicine and magic to craft prosthetic body parts for the child. Once Hyakkimaru comes of age, his adoptive father replaces his body parts with ones that incorporate weaponry, such as katana blades in his arm sockets and stun spray in his artificial legs.

“The series has a lot of qualities that are often associated with anime and manga. It’s trippy, creepy, gorgeously extravagant, and filled with a muted, yet outraged sorrow about mortality and impermanence. It’s one of Manga-no-Kami Sama’s loveliest, darkest and most overwhelming series. It’s also filled to the brim with a fascinating and endearing quality often found among brilliant artists trying to legitimize a medium considered pulp in its time.”

Hyakkimaru then wanders off to slay the forty-eight demons to reclaim his body parts one by one. Shortly after he leaves, he meets the young orphaned thief Dororo, who promptly becomes his sidekick. As with Tolkien’s hobbits, young Dororo forms the heart and soul of the tale, an ordinary child navigating a world of callous horrors with only his resourcefulness, heartbreakingly transparent bravado and an iron will to live.

The series has a lot of qualities that are often associated with anime and manga. It’s trippy, creepy, gorgeously extravagant, and filled with a muted, yet outraged sorrow about mortality and impermanence. It’s one of Manga-no-Kami Sama’s loveliest, darkest and most overwhelming series. It’s also filled to the brim with a fascinating and endearing quality often found among brilliant artists trying to legitimize a medium considered pulp in its time. Like the scatological humor of Shakespeare’s fools or the mustache-twirling villainy of a Dickens antagonist, Tezuka’s work is littered with cartoonish low-art charm. Just as Shakespeare’s fools spout wisdom and Dickens’ villains exude true terror, the cartoonish quality of Tezuka’s work is always floating above a lake of unspoken substance.

A large part of Dororo’s greatness and appeal lies in the basic premise and the extent of its execution. Tezuka shared common ground with the European Modernists in one vitally important respect. Like them, he wrote in the wake of the ghastly, cosmic disappointment of a World War. Consequently, Hyakkimaru’s incompleteness is deeply Modernist in its ambiguity. It feels like it should symbolize something, but because we never know quite what, it weaves a haunting aura throughout the work as a whole.

Dororo is pervaded by a sense of having lost something that was never had, of being deprived of a cosmic birthright by a world that was never as fair as imagined. Not only do Dororo and Hyakkimaru feel the sting of deprivation, but so do any number of helpless villagers heartbreakingly stripped of parents, lovers and children. Central to Dororo is the vulnerability and inadequacy of life in a world overrun with demons both literal and figurative. Equally central is the stubborn hope of those faced with them.

“There’s also the stunning dynamism of his action sequences. The fight scenes contain many elements that you’ll find everywhere in today’s action manga, like quick draw katana duels, leaping midair martial arts battles and rushing movement lines, but Tezuka approaches them with calligraphic restraint that one wishes was more common today.”

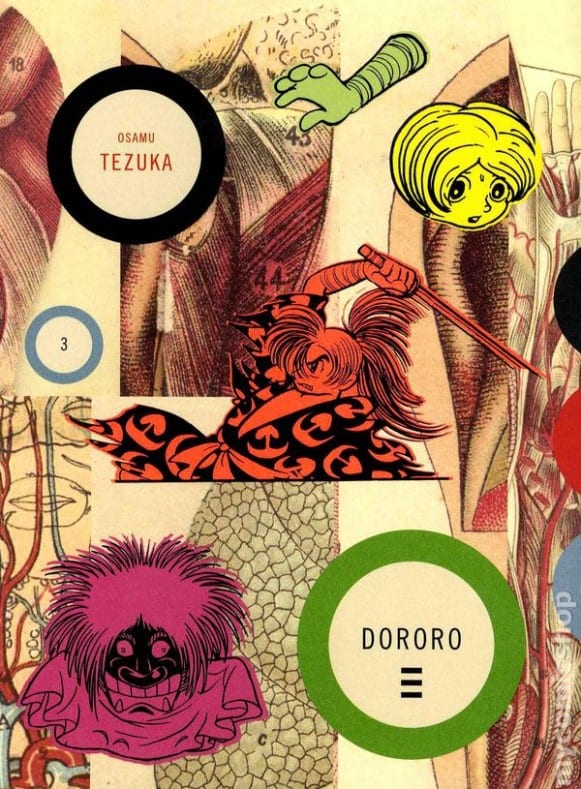

As always, though, a strong premise means little without strong execution, and Tezuka delivers. The second great source of Dororo’s appeal is the consistent excellence of Tezuka’s artwork, with a lushness, precision and neatness that is nothing short of unbelievable considering the man’s staggering output over his long career.

Like his comparably influential American counterpart Will Eisner, Tezuka is a master of the seemingly limited medium of black ink on white paper. He manages to achieve a stunning array of visual effects with nothing but lines and the space between them. While color is missing in the most literal sense possible, it’s impossible to feel its absence. Tezuka’s grass is greener, his blood is redder and his oceans and waves are bluer than in most Photoshop-colored comics.

There’s also the stunning dynamism of his action sequences. The fight scenes contain many elements that you’ll find everywhere in today’s action manga, like quick draw katana duels, leaping midair martial arts battles and rushing movement lines, but Tezuka approaches them with calligraphic restraint that one wishes was more common today.

It’s hard to say whether or not Dororo is representative of Tezuka’s body of work. Osamu Tezuka tackled a variety of dark and provocative subjects in his day, but a compelling argument can be made that his greatest legacy is as a childrens’ entertainer, with seminal works like Astro Boy still lingering as the cornerstone of his reputation.

If nothing else, though, Dororo is a great introduction to Tezuka’s works for those comic creators that want to understand Manga-no-Kami Sama’s importance to their medium. One of his greatest legacies both in Japan and in the U.S. was to prove unequivocally that comics and animation had all the range of established media like stage and the novel. An aspect of anime and manga that remains alien to Western audiences is their range, encompassing every age group and genre while Western comics are just recently shaking off their reputations as vehicles for superheroes, kiddie fare and nothing else.

In 1988, Japan’s Studio Ghibli produced an anime film called Grave of the Fireflies about two Japanese children who are orphaned by World War II and perish of malnutrition in the aftermath. This grim, adult premise would be unthinkable in American animation even now, and the fact that the Japanese managed a movie like it nearly two and a half decades ago is a sign of the scope of Tezuka-Sama’s legacy. It’s arguably only in the past decade or so that American comics have started to develop a rightful reputation as serious literature, and many Western artists like Will Eisner, Alan Moore and hordes of others worked nobly to bring that to pass. brilliant artists to bring that to pass, it’d be wrong to underestimate his influence, whether directly or through his many, many, many creative descendants.