In the lead up to the latest exhibition by Nigerian-born, American-raised artist Odili Donald Odita-his fifth solo outing since 2006 at Jack Shainman Gallery-all press materials pointed to this particular show being called Celebration. But in the days leading up to the exhibition’s January 5th opening, the show’s title evolved, one could say. It is now Third Sun.

“There is more than one way of understanding a piece of artwork or body of work,” says Odita over the phone, his voice resonating with an urgent sense of clarity. “These things are not binary, but multi-dimensional.”

“Evolution” as a word, works here because Odita has by no means thrown out all the implications of the word “celebration,” rather, he’s absorbed it. Much like the title of multi-media artist Nick Cave’s November 2017 exhibition at Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nick Cave: Feat, Odita also recognizes that a solo exhibition at a major gallery or institution, let alone a successful career in art, and by an artist of color especially, is no small feat, should not be taken for granted, and is continued cause for-you guessed it-celebration. But why the last minute change?

“Evolution” as a word, works here because Odita has by no means thrown out all the implications of the word “celebration,” rather, he’s absorbed it. Much like the title of multi-media artist Nick Cave’s November 2017 exhibition at Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nick Cave: Feat, Odita also recognizes that a solo exhibition at a major gallery or institution, let alone a successful career in art, and by an artist of color especially, is no small feat, should not be taken for granted, and is continued cause for-you guessed it-celebration. But why the last minute change?

“Third Sun means many things,” Odita offers, “but I’m thinking of it as a third try, maybe in an ecological sense, or a third option, or third space, as opposed to the third world or third people.” It should be noted here that this interview took place just moments after President Trump, allegedly, in an intimate Oval Office meeting, referred to several smaller countries, especially those in Africa, as “shithole[s].” Odita, who was born in Enugu, Nigeria in 1966, was only six months old when his family fled the West African country due to the Biafran war, a brutal civil conflict with lasting geopolitical implications.

“My father had a scholarship to study in America.He later became an Art Historian and founded the History of African Art and Archeology Department at the Ohio State University. If it weren’t for the kind people in America in the ‘60s who embraced international education scholarships, I wouldn’t be here. If this happened in 2017, I’m not sure if I would have drowned in an ocean. “

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Growing up in the Midwest (Columbus, Ohio), Odita struggled with this exact derogatory perception of Africa his entire life. Such extreme Western viewpoints in regard to the admittedly complicated nature of an entire continent (Africa is violent, backward, etc.) of course, become internalized, but to hear such callous rhetoric from the mouthpiece of our highest office (though not surprising) is not only triggering, but frustrating to an almost debilitating degree. Jordan Peele’s notion of a “sunken place,” coined and illustrated beautifully in his breakout directorial debut Get Out, might be the most appropriate metaphor for this suffocating, disheartening metaphysical state of mind.

“Celebration was something that was pivotal for me in 2016, after the presidential election,” says Odita. “It was a ‘create in vain’ situation as I was unable to make work for a number of months. I couldn’t really justify work being made under these auspices. I saw a certain kind of bullying and the denial of people’s accomplishments and traditions, the erasure of other people’s history, all as an absolute type of censorship. I understood celebration coming out of that as a means of acknowledging oneself despite those who wish to make you disappear.”

Third Sun, 2017, acrylic paint on wood panel (diptych), 92 x 54 inches (each panel), 92 x 110 ½ inches (overall dimensions), Inventory #OD17.012

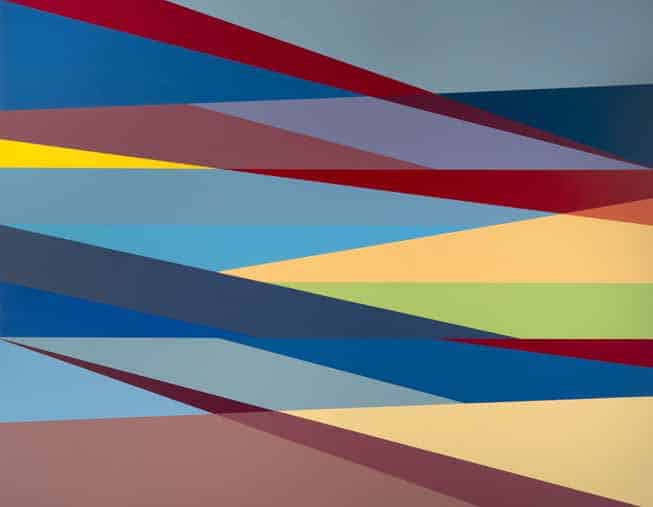

Great Divide, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 74 x 90 1/4 x 1 5/8 inches,

Inventory #OD17.011

Place, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 84 x 110 1/8 x 1 5/8 inches, Inventory #OD18.002

Celebration, one could say, is a kind of memorial in the face of struggle and the gross denial of human action. Third Sun, as an extension, is a greater appeal toward sophistication, a positive approach to an appreciation of complexity, despite the word “complex” often being used as a lazy excuse for topical dismissal. For Odita, this latest exhibition is evidence that he has and will continue to overcome personal, physiological and creative difficulty.

“The creative block I had was really about the overt racism that was openly spoke of and utilized to get the guy in office,” says Odita. “Some people laugh at this guy and his rhetoric, but someone was killed in Charlottesville. White supremacists were emboldened to say this country is theirs again. There are people of educated mind with prosperous lifestyles and jobs that voted for this guy despite his racist, sexist, xenophobic, heartfelt evil statements. That was a depressing time. After Obama, after the so-called world of post black kinfolk, I saw white racism and sexism come out in full glory.”

One of the more rewarding elements of speaking to artists at any stage of their career is discovering how they pull themselves out of a state of disillusionment-a psychological sunken place. “It came from a deeper understanding of what celebration is: an affirmation of what has been accomplished, that there is still a struggle and a fight. It’s not something that is done once but needs to be done every day.”

A great example of this exasperating truth, is the story of African-American architect Julian Francis Abele, who Odita deeply researched when he was commissioned back in 2015 to create two large-scale murals as part of “Nasher10,” a celebration of the first decade of the Nasher Museum’s founding and commitment to culturally conscious programming. Odita’s mural inside the Museum’s Mary D.B.T. Semans Great Hall, Shadow and Light, is inspired by the architect, the first ever black graduate of the University of Pennsylvania who is credited with designing most of Duke’s campus many years before he would ever be allowed to attend. In a tragic sense of irony, Abele was barred from even visiting the university due to fierce Jim Crow segregation in the South. Abele’s great-grand niece, Susan Cook, a sophomore at Duke, would later highlight this systemic expression of America’s hypocrisy in the university newspaper, not long after campus-wide South African apartheid protests in 1986 divided faculty and student body.

“Everything my parents told me, all these stories. They’re real,” says Odita, who like many marginalized voices debates whether or not he relaxed a bit too much during the Obama years. “Everything is real. We need to be alert.”

Monument, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 40 1/8 x 36 1/4 x 1 1/2 inches,

Inventory #OD17.006

Camp and Settlement, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 40 1/8 x 36 x 1 1/2 inches,

Inventory #OD17.005

The Other Side of the Wall, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 80 1/8 x 110 x 1 1/2 inches, Inventory #OD18.001

There is a similar conversation happening in the art world at large, built around the realities of equity, inclusion and representation. From a writer’s objective viewpoint, things are getting better. Though one is both eager and hard-pressed to say we’ve “turned a corner,” it must be noted that there is often another corner around said corner. This similarly allows for a corner to be turned (and celebrated) while remaining alert. For Odita, who has found a decade-plus home at Jack Shainman, a notoriously inclusive space for artists of color (a constant cause for celebration, not to be taken for granted), his perspective from a cultural epicenter of said conversation is fascinating to say the least.

“On one hand we have this good thing,” Odita begins, acknowledging this cultural shift. “Does the good wipe away the bad? Does the bad wipe away the good? I want to acknowledge accomplishment and what’s been successful, but also to understand that the struggle for quality and justice and creative freedom still needs to be worked out. Even with galleries like Jack Shainman or the Whitney Biennial, there’s oversight and missteps. We need to keep asking: How can we grow as human beings?”

As one might guess, the conversation turns to Dana Schutz’ “Open Casket,” 2016, the most controversial work at the recent Whitney Biennial, which depicted Emitt Till in a colorful meta-commentary on abstraction, authorship, censorship and cultural appropriation and invited several protests and boycotts. In diving back to this topic, Odita brings out a fascinating if not inherently problematic proposal: the democratic selection of potentially controversial, triggering works at massive public exhibitions.

“I ask myself the question: If we had public debate in discussing something as tragic as the Vietnam or Iraqi wars or the destruction of the Twin Towers, we would have a debate about whether or not we would include these pieces. This character (Till), this figure, is a monument. If there were an actual public debate before the work was presented, where would this painting stand?”

“I ask myself the question: If we had public debate in discussing something as tragic as the Vietnam or Iraqi wars or the destruction of the Twin Towers, we would have a debate about whether or not we would include these pieces. This character (Till), this figure, is a monument. If there were an actual public debate before the work was presented, where would this painting stand?”

This flips the entire art world paradigm on its head. Is art primarily a reactionary endeavor? An individual or a select few (the 2017 Biennial was co-curated by Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, both of Asian descent) are deputized to curate and select works, arrange them in a box or site specific setting and reveal it to the public, who reacts, for better or worse. So what if potentially controversial works submitted to the next Whitney Biennial were open to a preliminary public debate and selection? Who would be allowed to vote? Whose voices would be heard outside of the parties already in place at such an institution? Would Jordan Wolfson’s shocking VR piece, “Real Violence,” have made it in?

“I think art making and production is a reflection of human consciousness,” says Odita, after sitting on this for a moment. “I do feel that art needs to somehow, but not always, live above morality. Art should have the opportunity to challenge moral opinion, expanding upon those notions or rethinking the notion of what we understand in the world. But dealing with something specific, I think, in a monumental sense, in the case of what happened with Dana Schutz; I think something else should come into play. That is a responsibility, not by the judge and jury, but by the artist.”

But one has to ask: Did Schutz know exactly what she was doing? Was she abstracting the figurative, this human monument, himself abstracted, the larger story-also abstracted? Also, should Schutz maintain the right to offend?

“The censorship or self-censorship of political correctness,” Odita pauses for a moment, “I tend to look at it like a painting that’s just not that good. She needs to make better paintings than that. She (Schutz) said, ‘I’m a mother. I understand empathy.’ I have empathy for a lot of things, but do I have the understanding, the knowledge of the history of the subject matter? She should understand it more than just, ‘I’m a mother.’ Till’s own mother, in the face of politicians, the governor, against all the authorities that were there, said, ‘Keep the casket open.’ This is perhaps the single most Avant-garde action I can think of. In comparison to that small painting on the wall, it just falls incredibly short.”

Code Switch, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 92 1/8 x 68 x 1 5/8 inches, Inventory #OD17.009

Flag, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 42 1/4 x 36 1/8 x 1 1/4 inches, Inventory #OD17.007

For Odita, the action has to be understood and the action has to be real. This is the core ethos that he imparts to his students at the Tyler School of Art at Temple University in Philadelphia, where he’s served as a Professor of Painting since 2006 since 2006. But how can he help young artists find and nurture their most personal, unique voice in an increasingly political art world, and during a climate that demands activism as much as aesthetics? How can he push students who might not check marginalized boxes to push the envelope?

“They’re all struggling with these realities,” Odita says of his students. “Some ignore it and make art as entertainment, others really take on the pressure and responsibility that comes with being an artist. It’s about being there every day with them and understanding that there can be something deeper, while expressing their individuality.”

Code Switch, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 92 1/8 x 68 x 1 5/8 inches, Inventory #OD17.009

Odita enjoys engaging his students in the ongoing art-debate, this being that “there’s nothing original, painting may be dead, art may be dead, etc.,” but insists there is great beauty in understanding how each of us can be unique and original. “It’s the work that we each have to do to find our original voice,” he adds. “So much work is overproduced and cynical, but we have to find something pure and when we find it, treat it as special.”

And what about Odita’s unique voice? How can a fierce, professorial mind with an eye for social justice and activism create sufficient interpretive space for viewers who may not be familiar with the author’s race, gender, class, origins or his political views? How does the lay-public engage with his street murals, for instance? Odita’s somewhat abstract, elegant, acute fractal paintings, the contents of which he calls “bodies in space,” are not didactic or overtly polemic. At a time where Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald’s sure to be fabulous portraits of the Obamas could thrive in any major contemporary art gallery as much as their eventual home, The National Portrait Gallery, how can Odita’s colorful body forms translate and connect politically and should they even have to?

“Keith Anthony Morrison, a fine artist and intellectual of Jamaican decent talks a lot about the diversity of the black experience and the complexity of the black Diaspora,” explains Odita. “We continually have to overcome binary, simplistic thinking in terms of the black experience. The color in my paintings, they’re not the same blue, not the same red, not the same yellow. This is the same for black people: it’s not all the same hair, same culture, or same food.”

It’s this notion that activates Odita’s vibrant, audacious color-forms in a political sense. This striking but at times subtle complexity stands in the face of Trump’s ignorance; from his insulting, “What do they (black people) got to lose?” statements regarding the multifarious problems in black urban life in America on the 2016 campaign trail to his latest, myopic and grossly sophomoric viewpoints on African and island nations.

“ ‘It’s all the same people.’ That’s terrible,” says Odita, still trying to shake this new normal, which is unfortunately, for so many, just more of the same. “When working in abstraction as a person of color, like so many artists before me, I’m saying we have the freedom to express ourselves in an individual way. We need to allow ourselves to do that as much as we should ask the world to allow us to do that.”

ODILI DONALD ODITA

Third Sun

JACK SHAINMAN GALLERY

January 5 – February 10, 2018

513 WEST 20THSTREET NEW YORK, NEW YORK

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.