Brandon Boyd, the multi-talented Incubus frontman, whose artistic (image making) output has run parallel to-if not fully integrated with-his musical offerings for more than two decades, is taking over the Surf Lodge bungalow at The Confidante Miami Beach Hotel for this year’s larger Art Basel circus on December 6th & 7th. On Thursday evening, Boyd will host an intimate dinner for the Louisiana-based painter Ashley Longshore. Don’t hold your breath for Brandon and his boys to break out the hits, however.

“I’m going to do my best to let the art stand on its own legs,” says Boyd, “but I never say never. My good friend, also a very talented artist and musician, Natalie Bergman from Wild Belle, will be DJing, so there will be good music at the very least.”

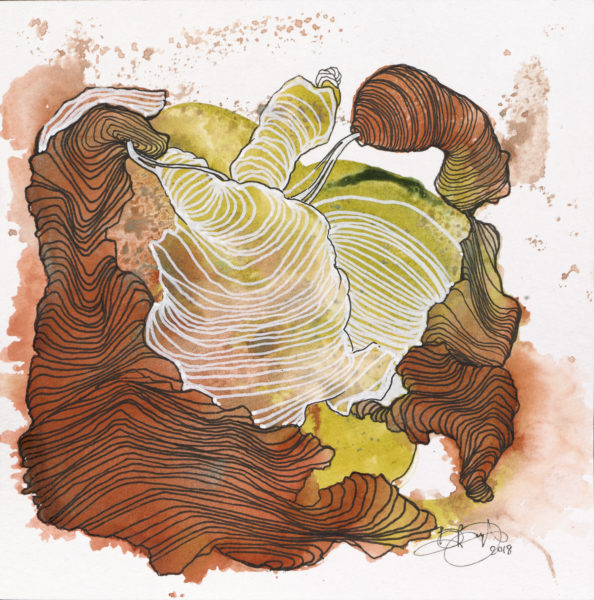

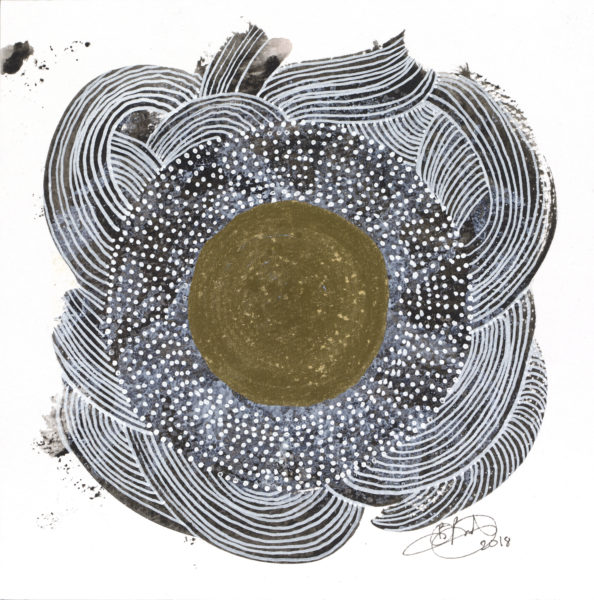

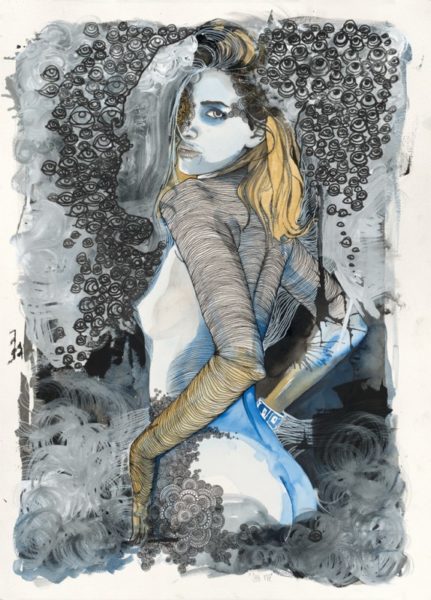

The lithe and long-haired Boyd will be showing a series of large scale, mostly abstract acrylic paintings along with a series of hybrid figurative works-a mixture of watercolor and acrylic-featuring tasteful female nudes (assuredly willing muses) wrapped in swirling painterly ribbons of floral smoke, along with a set of 13 small-scale (6 x 6”), colorful acrylic “Portals” he primarily executed while on a recent, 18-month tour with his band.

“3,” Portals, Series 3, 1-13, 2018 Acrylic on Canvas, 6 x 6 inches // framed

It’s natural for humans deeply embedded in the “art world” (and not much else) to recoil slightly at the idea of an artist, more famous for operating in another medium, to enter into the Basel feeding frenzy with a series of fine art offerings. The Ghost of Basel Past could easily sweep up an unsuspecting spectator and remind them of the shallow, uninspired works by a handful of well-meaning actors (especially) leaning on their marquee names to sell mediocre paintings, scoop up some extra-curricular (ahem) attention, and generally utilize the medium for a booster shot of cultural relevance.

“I’m just doing my very best to allow as authentic of a voice to emerge as much I know how,” says Boyd, who is quite aware of the celebrity crossover stigma and unconcerned by contemporary art chatter. “It’s not my intention to be apart of that conversation, so to speak. I make things that feel wonderful to be made.”

“9,” Portals, Series 3, 1-13, 2018 Acrylic on Canvas, 6 x 6 inches // framed

Boyd stands apart, precisely because he’s subtly woven his deft artistic hand, especially his impressive, sinewy line-work, into an ongoing generational dance with his storied and enduring music career. His earliest album art, band merchandise, tattoos and music videos have conspicuously featured his artistic efforts, manifesting often like trippy fast-twitch muscle fibers or universally spiraling alien jungle vines, reaching, stretching, climbing and relentlessly searching for a worthy limb to cling to. Boyd never (publicly at least) exuded the traits of the needy vine, or the incubus for that matter (each starved for symbiosis), but rather that of a rare archipelago, a sort of wildly unique human Galapagos, or a rollicking rolling stone.

“I never really involved myself, knowingly that is, in any scene, whether in music or art,” says Boyd over the phone from his home in LA and less than 24 hours away from hopping on a redeye to the soon to be buzzing city of Miami. “I was born in The Valley in Van Nuys, then I grew up in Woodland Hills, then I moved to Calabasas when I was a kid. I lived there until we started touring, and then, I lived nowhere.” Boyd was only 19 when Incubus started playing out of town. He was 20 when “…we started hitting it really hard,” he says. “Everybody in the band is roughly the same age. I remember having my 21st birthday in Toulouse, France. We were on tour with Korn. It was a trip.”

At a springy but seasoned 42, Boyd remains something of an island unto himself. His band-mates, who clearly shared and will continue to share this life-long trip, must be something closer to family at this point, but what about when the last encore concludes and the world tour comes to an end? What is one to do with all that silence? For Boyd, he’s been developing a more thoughtful, meditative, at-home studio practice, close enough to the action, but removed enough from the distractions.

Brandon Boyd. Photo by Julian Schratter for “OptiMystic” Pop Up Exhibition, Gallery One 11.

“It’s a remarkable place to be an artist,” says Boyd of LA. “If you’re creatively inclined, you can have a little bit of everything if you want it. From a distance it seems like a bustling art and music scene. It never really got the respect it was due. Or you can hide in the multiple canyons that we have here or vast cityscapes and just make things. That’s what I’ve been doing for most of my life. I haven’t been hiding exactly, but quietly keeping my head down while being inspired by the place, but not consumed by it.”

So what about diving headfirst into the “sceniest” of scenes, the urban embodiment of Instagram, Art Basel Miami Beach, the art world’s favorite “go ahead, eat your cake,” love/hate relationship? And what about doing a pop-up show with the Surf Lodge, a venue (its home base is in Montauk, NY) that developed quite the reputation over the last decade as a thumping habitat for scene chewing, noise spewing debauchery and popped-collar, rich kid apathy, despite its admittedly (and sometimes surprisingly) stellar art, music and lifestyle programming.

“1,” Portals, Series 3, 1-13, 2018 Acrylic on Canvas, 6 x 6 inches // framed

“Everybody [at ABMB] flies their flag as high and as much as possible. It’s such a thing,” says Boyd. “I have mixed feelings about it. It’s so much fun. Everyone comes out and shares what they’re making. It’s hard to get in everywhere. It’s the best and the worst of it. That’s what makes it interesting.”

The same could be said for the Surf Lodge, of course. It’s a flashy microcosm within a glitzier microcosm, and so on and so forth. Boyd will bring his art, good cheer, high cheekbones and accessible Zen vibes. It’s only natural that he would team up and show with an organization that supports art, music, surf culture and nightlife all in one well-made curatorial cocktail replete with actual well-made cocktails.

“I only recently just heard of it,” say Boyd, a life-long West Coast kid and certified global nomad. “It seemed like a good fit. I’m extra curious to see what these two entities slammed together is going to produce. It’s either the most insane shit show on the planet or the best thing ever. Probably both.”

“6,” Portals, Series 3, 1-13, 2018 Acrylic on Canvas, 6 x 6 inches // framed

Boyd will be exhibiting some new pieces at the pop-up, but also a handful of works previously shown at Samuel Lynn Galleries in Dallas, Texas. These were shown this past May in a solo exhibition called OptiMystic, a play on words that posits extreme foresight as a potential sabotaging agent to a future of smooth sailing. “There’s something that occurs to me periodically and somewhat randomly when I’m making a cup of coffee,” begins Boyd, honestly and rather humbly when pushed to reflect. “It’s something like, ‘What a unique experience you’ve had so far.’”

Boyd’s work is reflective of the highs and lows, the light and the dark sides of being a front man for a major rock band, one that, despite the passing decades and a shifting pop-culture landscape, still pulls quite the draw and a hefty quotient of the female gaze. Maybe that’s why his slightly sexualized, conventionally attractive female nudes seem to be culturally and artistically permissive. It’s an outright energy exchange he’s used to at this point. However, the hand and finger-painted swirls, or nebulous choral shrouds, hint that things are a bit more complicated than meets the eye.

“See Me,” 2015, Ink & Watercolor on Fine Art Paper, 30 x 41 Inches

“At some point a handful of years ago I realized what I was working towards, was a sort of fission in the line work, which had become something of a hindrance,” he says. “I had created for myself a barrier to the freedom of my hand, to paint big, to have more expressive strokes-pushes, spills, splatters, splashes-on larger pieces.”

Managing an exchange of energy and emotion, especially those at extreme poles and through self-made imagery as the conscious medium, is what art is all about. It’s about acknowledging where one has created their own or perceived external barriers and then doing what is required to break them open.

“We just did a show in San Bernardino with our friends, System of a Down, in a really big venue,” says Boyd. “There were 50,000 people in front of us. There’s no real framework for that. Sometimes I wake up in the midst of this remarkable dream, but then I wake up again, and realize it’s all part of the process.”

Imagine a raging, sold out crowd at the Glen Helen Amphitheater, then take a moment to think of Boyd, a dynamic, highly frenetic physical presence onstage, noiselessly obsessing over his highly detailed line work, whether at home or lounging on the tour bus. He doesn’t paint to music, but rather the sound of birds chirping or his dogs gnawing happily on a bone close by. “Sometimes when I’m sitting there drawing or painting, a song will show up,” he says. “I’ve learned to just shut up and let it come through.”

“Starry Eyed Sonata,” 2018, Acrylic On Canvas, 50 x 50 in.

Scene set. So where, when, or how did Boyd stumble onto his own unique line, these thin, tenuous, often wormlike threads? Did he find inspiration in Picasso, Matisse, Haring, Hockney, Goya, Emin or Condo? Maybe the painter Paul Klee inspired the globetrotting artist when he famously said, “A line is a dot that went for a walk.”

“Growing up, the artists I was obsessed with as a kid were illustrators and graphic artists,” he says, “everybody from the San Francisco, psychedelic poster art scene, like Rick Griffin and Stanley [George Miller] Mouse; these guys who were doing Grateful Dead posters or Jefferson Airplane. I had these books and I would get high and just dive in and stare at the line work. It was worthy of an extended gaze. It’s easy culturally to look at it and deem it a fad, but to me there was so much more in it because it was somewhat representative of the music, which I always had in me as well.”

“13,” Portals, Series 3, 1-13, 2018 Acrylic on Canvas, 6 x 6 inches // framed

Boyd later became obsessed with artists like Aubrey Beardsley (the line, the spiral, the decadent, the erotic, the poster format) and Egon Schiele (the emotion, the tortured but sensuous figures, the self-scrutiny). It’s mentioned to the wiry front man that he, in some ways, looks like a living Schiele character. “I’d be flattered if that were the case,” he responds in good humor. “The colors in his work; the brown and green, the figures, they’re not traditionally beautiful, but he’s capturing the beauty in the grotesque, the grotesque in the beautiful.”

Boyd seems to do his best work when his unbridled dynamism collides with his own obsession (his signature hand, erased, fighting to return, again, obliterated), perhaps best illustrated (in image and title), by the large-scale acrylic on canvas piece, Wild Horses Running Wild, 2016. While taking in this piece, one envisions Brandon, a marvelously weathered Atreyu archetype, chasing after a fleet of wild stallions in order to break the most glorious steed in their band, simply for the sport of it all, only to graciously concede to their power, beauty, and freedom, then sit back, sigh and revel in the view.

“Wild Horses Running Wild,” 2016, Acrylic on Canvas, 78 x 78 inches

“There’s a feeling attached to it while it’s happening,” Boyd says of his process. “So much so, the feeling is so wonderful the vast majority of the time. It’s almost sad when a song or painting is finished. This fling or love affair comes to an end. You fall in love with a color spectrum or sound you discover on an instrument you thought you’d never pick up again, and there’s something really wonderful and simple about that. You’re a child; [there’s] no intentionality other than it feels good. I used this comparison all the time. You’re walking with the wind or petting the cat in the right direction. Pet the cat in the wrong direction, you get swiped, in the right direction, you create this relationship and it starts to purr.”

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.