“One of the best shows you ever had, boy.” Muhammad Ali

If anyone on the planet could have handled Dick Cavett, it was his longtime friend Muhammad Ali. The three-time heavyweight champion of the world appeared on the Dick Cavett Show more than a dozen times and hosted it once because of mutual love and respect. At the opening of one of his shows, Cavett said, “There are probably no great compliments that I can pay my next guest that he hasn’t already paid himself but I happily join him and millions of others. He is without a doubt one of the greatest sports figures the world has ever known. Just in case he can hear me, he is the greatest sports figure—charming, good looking and a heck of a nice guy.”

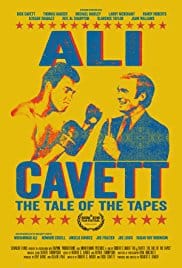

Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tapes, co-written with another of Cavett’s longtime friends and collaborators Robert S. Bader, is the culmination of more than three years of work. What started out as an archival project between Bader and Cavett somehow grew into a documentary comprised of more than a dozen interviews between Cavett and the man “arguably the most gifted orator to ever wear a pair of boxing gloves.”

Photo Credit: Courtesy of The Dick Cavett Show

Now if you don’t know who Dick Cavett is you probably were born after 1980. Google his name, go down the internet rabbit hole, and then come back schooled. Dick Cavett is considered to be one of the world’s most experienced and beloved interviewers, the host of various eponymous talk shows from 1968 to 2007. His recordings are truly documentations of modern history. Watch him turn his interview with George Harrison around after a painful 14 minutes. Most current nighttime talk-shows have guests on for four minutes. Cavett had guests on for ninety minutes. If the segment is going sideways, it is a long thirty-six hundred seconds.

But with Ali, the relationship was eminently special and eternally playful. Ali never missed an opportunity to upstage his host and, like a good host, Cavett graciously and with apparent genuine admiration demurred. “See, most boxers can’t talk like this, they’re not this intelligent,” Ali noted. “I mean you’re a witty man, they pay you to sit up here and think; you’re a brain. I’m handling you.” To which, Cavett gave the only possible answer, “I know.” Both men are smiling, Ali has a look on his face that can only be described as respect and mischievousness combined and Cavett looks like he is having a blast.

Today, at 81, Cavett is as sharp and funny as ever, though he suffers from a terrible affliction called “the anagram curse” that only affects a small portion of the population. He claims, “They come unbidden. If I bid them, they don’t come. As Groucho [Marx] would say, I knew a girl like that once.” It’s dumbfounding what Cavett did with the letters from Alec Guinness.* My only quibble is that he told me a couple of stories that I’m not supposed to use, not because they are untoward in any way but because you would know what to stop and ask him on the street about and he has places to go. He is unlikely to say no and is just about the politest person you could ever hope to meet. Bader, also the film’s director, started out as a college intern who was told not to bother Mr. Cavett but couldn’t help himself. He’s been working with him for the last several decades and is equally nice.

The following is an excerpt from a conversation that I had with Dick Cavett and Robert S. Bader at SXSW where the film premiered on March 11, 2018. It has been edited for brevity and clarity:

Jennifer Parker: How did you meet Ali?

Dick Cavett: I met him on the sidewalk in front of the Jerry Lewis Theater. He was there to be on the show and I was a writer, and I went out and thought, “Well, now I’ve seen Muhammad Ali.” Then they said, “Cavett, you have a job on this show. We want to put up a sort of a Roman forum and Ali will read poetry” since he was … at that point famous for his doggerels and things that he did over and over. I wrote poetry for him for that show. Even then, I thought, this is the last I’ll see of him, of course. What other reason would I have to run into Muhammad Ali unless he came to my hometown? Although, I was already living in New York.

JP: With more than a dozen appearances on the Dick Cavett Show, how did you decide what to include in the documentary?

Robert S. Bader: It took three years to really get that to work right because I had the horrendous problem of having too much good material. And that’s not just from the Dick Cavett shows. The people I interviewed had a lot of interesting things to say about Ali, about Cavett, and about the shows. Guys I interviewed remembered watching them and how special they were at the time. Particularly, I was shocked to find out that Al Sharpton made it a point to not miss the Cavett Show if Muhammad Ali was on. I don’t know that he watched every night but …

DC: Well, he’d almost have to.

RSB: Yeah. When it was known that Ali was going to be on The Dick Cavett Show, it was a big deal in a community that probably wasn’t [comprised of] regularly devoted viewers… Ali probably changed your demographic every night he was on.

DC: I’m sure he did.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of The Dick Cavett Show

RSB: Because Al Sharpton in Brooklyn and Juan Williams…These guys were like, “Hey, Ali’s on the Cavett Show, click, click, we’re watching that.” Their perspective on it was really interesting and, in some cases, unexpected. I told them what this [documentary] was about, and I got more about them remembering him on The Dick Cavett Show than I was expecting.

DC: Yeah.

RSB: When I first approached Juan Williams to be in the film, it was mostly because of him having written the book Eyes on the Prize, and I wanted that period in Ali’s history to be covered by someone who really knew his stuff. But [he’s] a huge Ali fan and a huge boxing fan and his father was a boxing trainer. And I didn’t know that.

[He] just knew so much about boxing and… Ali’s career that that was almost like having an extra interview… I got all that historical stuff from Juan Williams about the culture of the times, about Elijah Muhammad and Martin Luther King, and the obvious things… But then he’s talking about specific punches in the Earnie Shavers fight, in 1977. I’d say, “My God, this guy could also be a boxing commentator.” I’m getting the kind of stuff out of Juan Williams that I was expecting out of Larry Merchant.

DC: Yeah.

RSB: That I also got out of Larry Merchant. But you know what was also interesting? The people that I interviewed just have a genuine love and affection for Ali that … they don’t have to announce it. Even a veteran sports writer like Michael Marley or Merchant [who have spent] many, many years commenting on boxing and writing about sports. You can just feel that they had an affection for the guy.

DC: Yeah.

RSB: It’s a little too structured now. It’s very predictable. It’s like insert actor here. Show film clip. Next guest. And that’s sort of a turn-off if you’ve watched a lot of The Dick Cavett Show. This project came as a result of basically managing The Dick Cavett Show archive and being moved enough by two columns he wrote for his Times blog in 2012 about Ali to say, “Damn. I gotta do something with those shows. There’s something there. There’s a story there, there’s a way to tell that story in really interesting way because of how different those Ali interviews are and because of the fact that they’re the only interviews where Ali said certain things about himself.”

DC: Yeah.

RSB: There are people who’ve done Ali documentaries and Ali books who have told me in the course of my making this film that, “Oh well, there’s no footage of him saying this thing, and there’s no footage of him saying that thing.” I said, “Oh yeah, there is.” So that was actually very encouraging to find that the people thought that Ali didn’t record certain things on tape, which we have.

DC: Which we have.

RSB: That was a real interesting way to look at it, you know. I thought, “We’ve got something here that’s different.” Because Ali’s story has been told so many times. And I was also conscious about not wanting to make a boxing film. I don’t care much about boxing. I watched boxing as a kid because of Ali. I mean, that’s what you did if you were a teenager…

DC: A lot of people –

RSB: During the years I was a teenager, Muhammad Ali was everywhere. He was everything.

DC: Yeah.

RSB: My dad took me to [see] Ali and Norton III [fight] at Yankee Stadium in 1976. And I had never decided I wanted to go to a boxing match, but I’m glad I got to see Ali, even though I sat probably about 300 miles into the stratosphere of Yankee Stadium. I didn’t really see that fight ’til it was on TV a few weeks later. But I was there!

DC: Thank God I was there.

RSB: Ali was in the culture… Ali had a comic book, Muhammad Ali vs. Superman… [As] soon as Ali stopped fighting I kind of stopped watching boxing. I watched it a little bit longer, maybe while Larry Holmes was champion, then a little bit during Mike Tyson. But beyond that, I paid no attention to boxing whatsoever. I realized I liked boxing because of Muhammad Ali and then when he was out of it, I was out of it.

JP: But I think it almost had nothing to do with boxing. It had to do with him. He was this beautiful, charismatic, dynamic person who could’ve done anything.

DC: Yeah. He could have done the same thing for sewing.

RSB: He had those unidentifiable qualities that make people [into] movie stars and rock stars… and he didn’t do those things. He boxed. [What] I found sad about his story is, when he could have stopped and not gotten as impaired as he ended up becoming, there was another career waiting for him. Anything he wanted, he was that dominant a media figure. He could have done anything.

JP: Right.

RSB: He didn’t have to fight. But I know that the people who were making a lot of money on Ali fighting were not anxious for him to quit. And there was, well as much money as he could have continued making, going around the country just being Muhammad Ali, and going on TV and being Muhammad Ali-

DC: Yeah, he could have done a lecture tour.

RSB: It’s pretty hard to make 10 or 12 million dollars you know, for 45 minutes of beating somebody up.

DC: I would have written a lecture for him.

RSB: Yeah, exactly. Yeah, it’s just hard when there’s a lot of people making a living on what you’re doing.

JP: The other thing that was tragic to me was the times that he lost there were so many hits that he took that were so devastating.

RSB: I’ll tell you something that I learned from some of the boxing experts who were in the film… He was 29 and O when they took his title away. Nobody ever hit him. Every one of those fights, he hits the guy at will; he knocks people out in the first couple of rounds. Nobody lays a glove on him. Nobody ever hurts him. Ali never got knocked down; he never took a serious punch where he got hurt. And then he comes back after four years and he’s a different fighter ’cause A, he’s older and slower. B, he suddenly has to learn how to take a punch.

And people were hitting him, and hitting him a lot. And he’s winning. He only had three losses in that first major part of his career… He ended up being 56 and 5 and he lost those last two that he shouldn’t have been in.

DC: Boy.

RSB: I mean, this guy when he was getting beaten up, was still winning. So, fights in his later career, like the first Frazier fight, Frazier looked worse after beating Ali… than Ali did!

JP: And that’s when I started thinking about how we take advantage of athletes. We make them bigger than life. Ali could have done anything he wanted to do and yet, he chose this path.

DC: Yeah.

RSB: A couple of guys, these very articulate, older gentlemen who grew up watching Ali, break up and get a little emotional on camera when they’re talking about some of the things in Ali’s life and career. And there were [some] things that were said where I was behind the camera and I was almost in tears, [like] when Juan Williams is saying, “Yeah, I know he’s Superman, but Superman’s getting hurt here.”

And I remember how I felt when I heard him say that. [You] know, when you’re shooting interviews, you just kind of hope you get the right stuff… I had to try not to make a sound when I heard that. That happened to me a couple of times. Juan Williams really broke down talking about Ali’s decline and so did a couple of other guys. And it was just moving to me –

DC: Live?

RSB: Yeah. Just when I was sitting there doing the interview-

DC: Uh-huh.

RSB: I said, “I’m glad the camera’s not on me right now, ’cause I’m gonna cry.”

DC: I know

Photo Credit: Courtesy of The Dick Cavett Show

DC: Many scenes from my life are with him, horsing around. I treasure that. It was just a wonderful feeling to be around him. He had a magic that was palpable when you were with him. There was a documentary that Ali and I were in, and it was shooting out in Montauk. Ali had been depressed and I had been called. After we finished shooting, we went out to dinner in a restaurant and I said, “Just for fun, why don’t you stay at my house tonight?” And he said, “I want to see how you live.” I took him back to my home and got him settled in bed and headed to the hotel to get his wife. My wife, who was in New York, called while I was out, and Ali answered. She said “Honey.” He answered, “This ain’t honey, this is the three-time heavyweight champion of the world and I’m sleeping in your bed, watching your TV.” She responded, “I will make sure a plaque is put on that bed, Mr. Ali.” That’s more than she ever did for me.

At the end of the interview, Mr. Cavett hugged me and said that he was going to miss me. I told him that I bet he says that to all the girls. Finally, I have something to put on my headstone. I echo the sentiment, “Best interview you ever had, girl.”

*Anagram of Alec Guinness is Genuine Class.

Jennifer Parker is a Manhattan-based writer and mother. The editor in chief of StatoRec, Jennifer’s film criticism and author profiles have appeared in At Large Magazine, Fjords Review and the Los Angeles Review of Books.