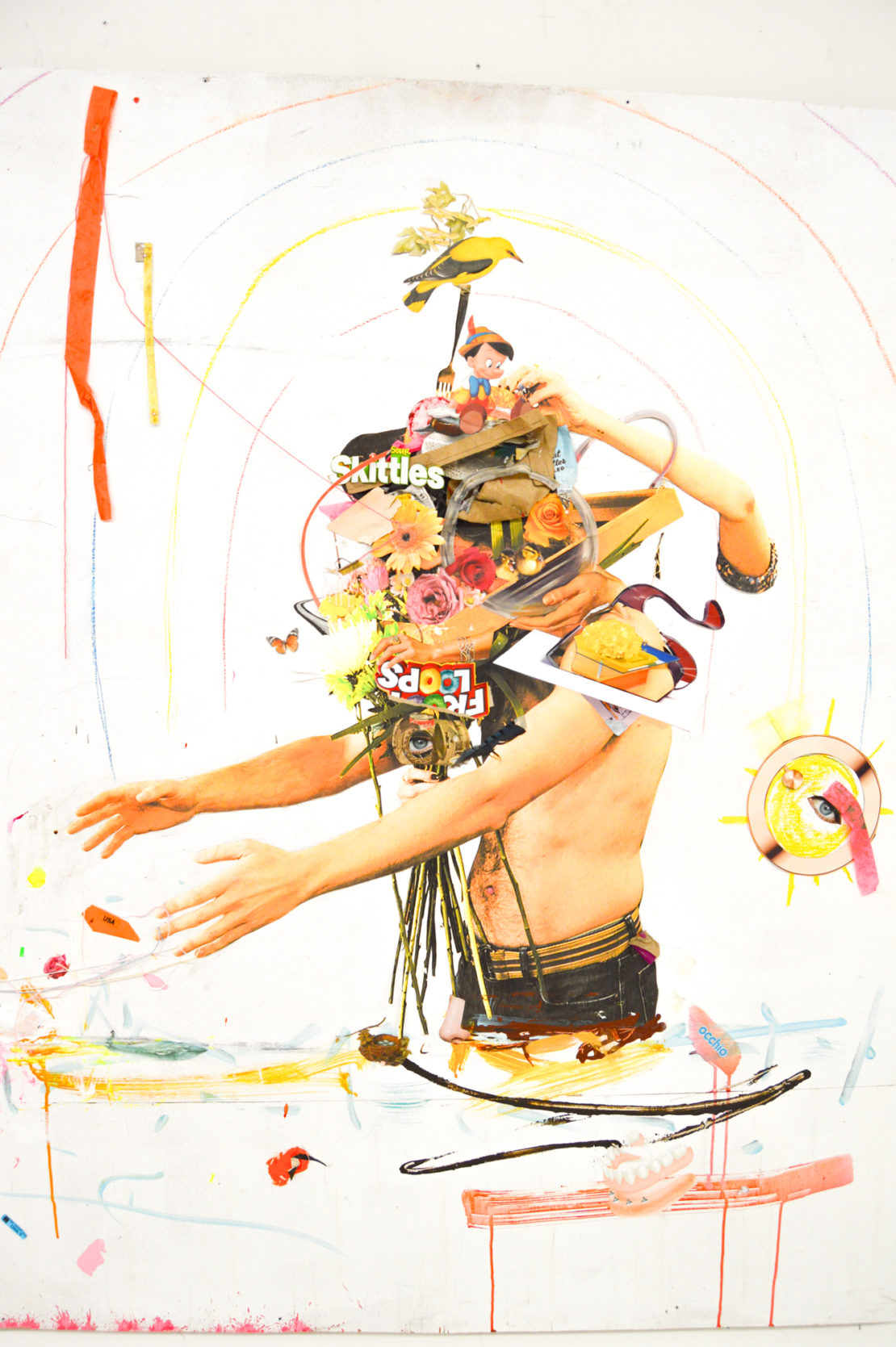

It’s a mid-October afternoon and mixed media artist Gilbane Peck is working on a series of “fine art glory hole paintings” in his corner studio in the 56 Bogart gallery and studio complex. Peck was a clear standout at this year’s installment of Bushwick Open Studios, where he also put on a short-lived, pop-up solo exhibition called Sunshine and Rainbows in his friend, the photographer Oli McAvoy’s versatile, light-filled studio space, directly adjacent to his own.

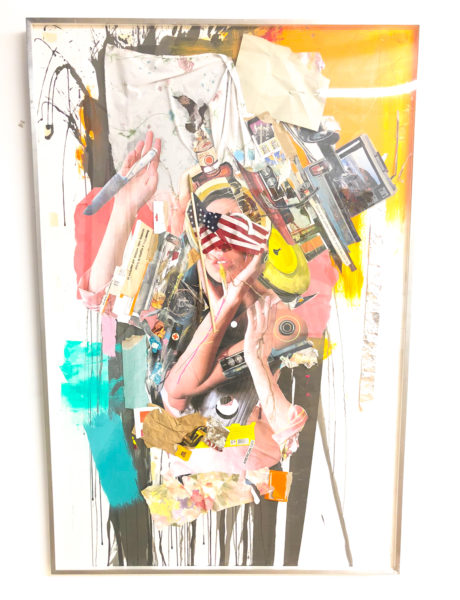

Image courtesy of the artist.

“My claim to fame is I sold the first fine art glory hole painting outside of the Whitney Museum,” says the soft-spoken, longhaired Mr. Peck with a quaint smile and a muted giggle. Peck wants you to know he makes “dick paintings” too, which he hopes to sell outside every major art museum: “So I can brag to my grandkids down the road.”

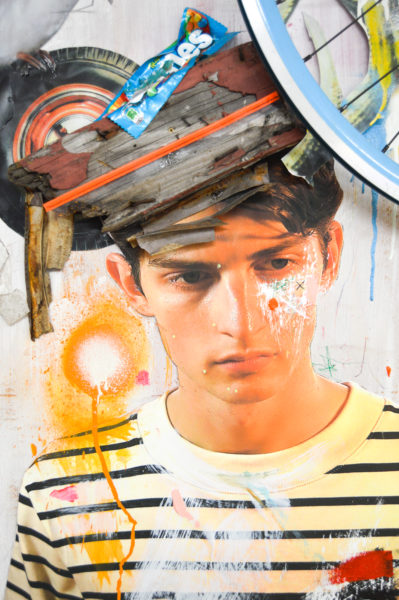

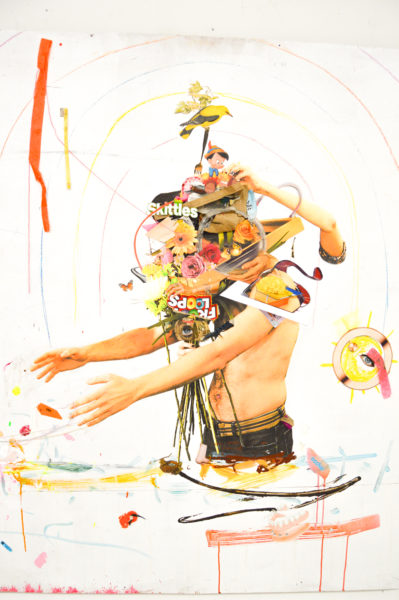

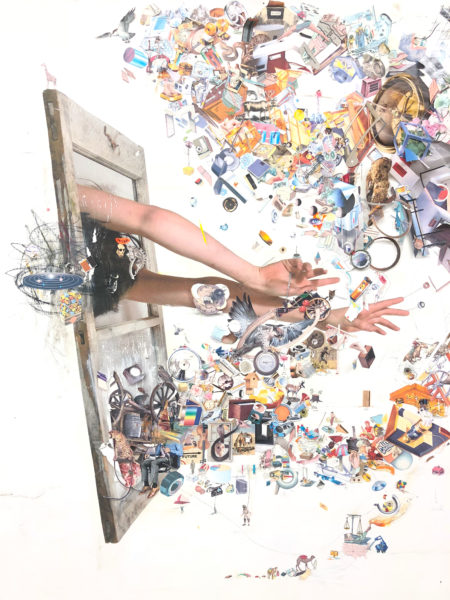

As silly, sexually deviant and DIY as Peck’s works can be, they’re objectively pretty damn good. Some are even great: unique, instinctually (confidently) composed, inventive, playful, different, funny, melancholy, colorful, improvisational, but somehow just, right. An institution like the Whitney might not be ready for fine art glory hole paintings, but Peck and his irreverent works (a mixture of sculpture, photography and mixed-media assemblage), based on size, skill, quantity, emotional potency and execution, are more than ready for a worthy but daring white wall.

Image courtesy of the artist

“I did one the other days called Three Way,” Peck adds impishly. “It features a three-way between God, me and the devil. I collage all over it. I sold three of those so far.” Peck is also working on a series called “The Ugliest Artist in the World,” which is about a character-Peck’s artist avatar-that only does self-portraits. “…But he doesn’t own a mirror, so he’s never seen his own reflection. He doesn’t even know what he looks like, so each one looks completely different. I’ve done some ugly portraits as dick paintings too, so there are crossovers between all these different styles and bodies of work.”

Image courtesy of the artist

Peck isn’t the only young artist having fun with their paintings. Alexandra Rubinstein’s work is a good example of irreverent sexual humor being utilized as an icebreaker for larger socio-political commentary, in her case, the celebration of the female gaze. Where so much work is about systemic oppression, pain, fear, violence and the horrors of history, a small yet seemingly disparate community of artists are trying to deliver their own perspective on the difficulties of life-sexuality, failed relationships, personal trauma, missed opportunities, class struggles-but with a well intentioned laugh.

“You have to be funny,” says Peck. “I use comedy as a way to not be mad. NYC and the art world and fine art, it’s easy to get mad. This is comic relief.” So is Peck mad at the art world or mad at society at large? Or is it both? “It hasn’t been easy, but people look at me like a healthy white male and they wonder, ‘Why are you on the street practically begging people to buy your art? Aren’t mommy and daddy paying for everything?’ No, they’re not.”

Image courtesy of the artist.

Peck has a background in hard labor. This comes in handy when constructing his makeshift art booth near the territorial, pop-up merchant space under the Highline in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District. “My father was a poor carpenter,” the artist begins. “He lives and works out of his van. When he’s not there, he squats in this house in Branford, Connecticut.” Peck grew up in North Guilford, about an hour and a half outside of NYC. “My mom is a cleaning lady. She’s had two knee replacements. We come from a hard-working family. I’ve never had anything laid out on the table.”

Image courtesy of the artist

Peck has two older sisters and younger brother. His parents were “always divorced.” He comes from a “broken home” with various “steps dads and stuff.” Peck knew getting into college-any college-would be his only way out. He got accepted to one and one only: Green Mountain College in Vermont. “It’s in the middle of the woods,” Peck explains. “Environmental Liberal Arts is their keystone. I got there and quickly failed every class. I was never good at school. All I knew was skateboarding and bass guitar. When I wasn’t doing that I was dropping a lot of acid and wandering around the woods. But I felt good in art classes. Somehow I turned it around.”

Green Mountain College’s general mission inspired Peck to make simple, sustainable art. His own practice began when someone gave him a hand-me-down camera. “When I was tripping, I would take photos or make weird little sculptures out of found materials. It would just happen. It was a different step. It was just about doing something.”

Image courtesy of the artist

One day, Peck was walking behind the school and found an oil drum lodged in a tree that was leaking into the river. “This was right in the back of an environmental art school,” Peck says, quite aware of the irony (hypocrisy). “So I made a sign, a sort of installation out of driftwood and wire that said: ‘Do you know what’s in your own backyard?’ It quickly got some attention and the drum was removed. That’s when I knew art could actually have an impact.”

Peck graduated in 2009 and even won his school’s Fine Art Senior Award. Soon after however, he was back in Connecticut squatting in his mother’s foreclosed home with his friend Juice and other characters with colorful names. “It was a house my mom had bought with a different crazy step father before they split up,” says Peck. “Mom was in a lot of trouble. Her business had gone under (selling personalized children’s toys). She was totally bankrupt.”

During this difficult window after graduation, Peck would play small music gigs in New York and go to a lot of art shows. (“I was always trying to get here.”) Sensing he was about to get the boot, Peck began frantically applying to various artist residency programs. Just a few days before total eviction he was accepted by the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, a 100-year-old artist colony in upstate New York. “I was saved.”

Image courtesy of the artist

Ready for a little Upstate hippy humor courtesy of Peck? What do they call a guy in Woodstock in the winter without a girl? Homeless. During his time at Byrdcliffe, Peck further explored ceramic sculpture, woodcarving and bronze figuration. He also kept up with his photography and his penchant for collecting weird stuff in the woods. But as it’s wont to do, summer quickly flew by. “Luckily, I lucked out again,” says Peck. “I met this girl who played violin. We started playing music together and she let me move in with her, so I was able to stay after the residency was over. I met good people, started landscaping, doing carpentry, and then I got a ceramics assistant job at the same residency.”

Peck moved into in a little cabin with a giant hole in the roof because a tree had fallen through it. “They knew I was the only guy crazy enough to live there.” Pecks’s girlfriend took one look at the place and that was a wrap. To be fair, his new duties at Brydcliffe were far from glamorous. They turned out to be mainly custodial, but he kept creating and soon found another girlfriend and then another art studio that he still uses to this day, just a couple towns over in what he calls “forever wild property.”

Image courtesy of the artist

Soon, his new girlfriend got an apartment in Brooklyn. “She also broke up with me because I was too poor, but that was the push that made me get a studio here (Bushwick). I got a studio just down the street in 2017. I was there for a while.”

Enter the previously mentioned Oli McAvoy. “He works for Hypebeast. I did a lot of assistant work for him,” says Peck. “He was in this place (56 Bogart), saw this studio was open and said, ‘Dude, get over here.’ This [studio] is the nicest thing I’ve ever had in my entire life.”

It’s only been a couple months in the current studio, but Peck is cranking out quality work. His compositions feature everything, not excluding one or more kitchen sinks. Some of his best pieces feature things like arrows, bicycle tires, discarded frames, warped self-portrait imagery, forks and knives, literal garbage, old fashion ads, and even strange little coloring book flowers colored in by Peck’s grandfather and cut and pasted back onto his canvases. Peck’s works are a beautiful, meticulous mess or as he says, “Controlled chaos.”

Image courtesy of the artist

“It’s about trying to escape to a more youthful place in my heart and mind,” he says. “I want to create something of another world, something I haven’t seen before.”

Outside of his pop-up solo in the McAvoy’s gallery/studio, Peck recently created an installation piece for an NYU group student exhibition. He also had a unlikely residency on the roof of the Hotel Americano in Chelsea. Most days, you can catch him by the Whitney sending smiling happy people home with a fantastic glory hole painting not far from where his current girlfriend, the model, musician and artist Kamryn Harmeling draws delightful five-minute portraits for the steal-price of five dollars.

“I’m very naïve,” Peck adds. “It’s been years and years and struggle. I could put work on the walls, legally, and not show my face and hide in the studio, but in the streets it’s about the people. They want to interact and have an experience. I want to be free, youthful; playful-make people smile and just feel good. I also want to feel good about the materials, that’s why it’s found materials as much as possible. When I look back, I want to feel proud. I feel like the art world can be about endless precious resources and manpower. It’s money wasted on the rich. I want to do things differently I guess.”

Image courtesy of the artist

Kurt McVey began his journalism career as a prolific contributor to Interview Magazine where he covered emerging and established names in the art, music, fashion and entertainment worlds. He has since contributed to The New York Times, T Magazine, Vanity Fair, Paper Magazine, ArtNet News, Forbes, Whitehot Magazine, and many more. A Long Island native, McVey is also a successful artist, model, performer, entrepreneur, and screenwriter working out of NYC.