Titled Viva Arte Viva, the 57th international art exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia is a call to celebrate artists, their ways of life, the forms and practices they choose. Divided into nine chapters or trans-pavilions, the exhibition curated by Christine Macel, Chief Curator at Centre Pompidou, presents itself as a route to stimulate dialogues and encounters with several “families of artists”. Indeed as for the curator’s intentions, the exhibition is transnational in its opening the Venice biennale to 120 artists (of whom 103 invited for the first time to the prestigious biennial) all coming from different parts of the world.

Also, it does represent a journey for it being driven by a positive energy and prospective approach that progressively give form to Macel’s “passionate outcry for art and the state of the artist”. Yet, the work of the invited artists is arranged in the pavilions/chapters in accordance to vague categories such as time, colour, tradition, books and passions which in a sense betray the curator’s proposition to present an organic exhibition, fluidly unfolding in front of the spectator. Rather than drawing visitors into an experience of today’s state of art, the exhibition offers itself as a chronicle of the current status of contemporary art, an anthology of the several microcosms composing its variegated scenario.

John Latham. | Various works, 1959-1992. | Mixed materials.

(Photo by: Francesco Galli, Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.)

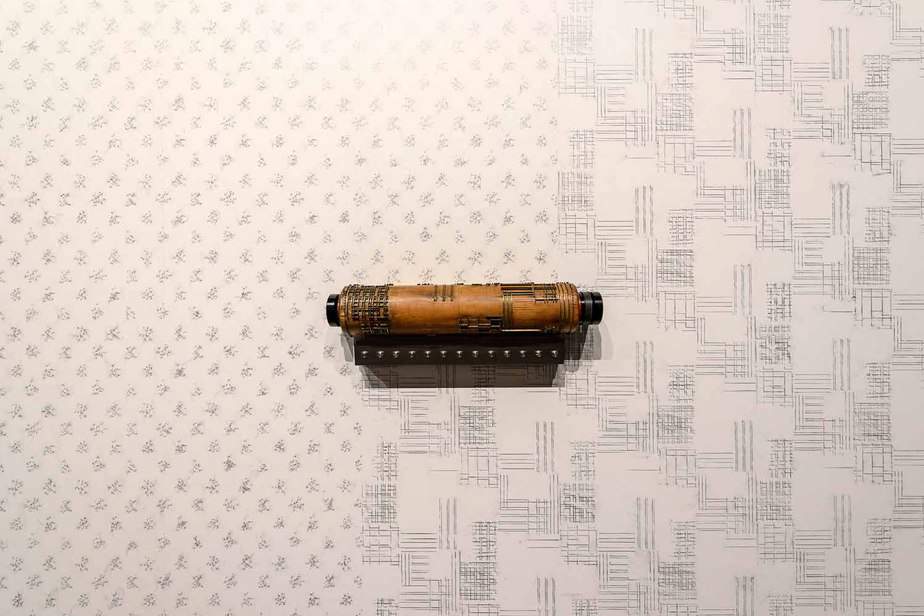

Anri Sala. | All of a tremble (Encounter I), 2016. | modified vintage wallpaper printing roller, steel comb, pencil drawing on wallpaper, electric motor and customized motion control software.

Not surprisingly, the first chapter of Christine Macel exhibition-as-a-book is The Pavilion of Artists and Books situated in the central pavilion at the Giardini. Indeed, the pavilion reveals the exhibition’s premises inasmuch as it offers the linear and almost instructional presentation of artists working with books and investigating in their practices the sense and importance of otium, the time dedicated to unproductivity and meditation in Roman times. Here we find seminal artists such as Mladen Stilinovic, John Latham, Philippe Parreno alongside highly talented, younger practitioners such as Ciprian Muresan, Søren Engsted, and Petrit Halilaj (who received a special mention from the jury along with American pioneering artist Charles Atlas). The second chapter presented in the central pavilion, The Pavilion of Joys and Fears, unfolds like a sequel of several solo shows. Each artist has been assigned an entire room, or a specific corner to present his or her most peculiar and representative works, leaving no possibility at all to look for connections and find new correspondences between the different works, and the different microcosms they aim to represent.

- Charles Atlas. | The Tyranny of Consciousness, 2017. | five-channel video installation, color, audio: helm and Lady Bunny, 23’44’’. (Photo by: Andrea Avezzù Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia)

- AUSTRIA PAVILION. | Erwin Wurm. (Photo by: Francesco Galli, Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.)

- GERMANY PAVILION. | Anne Imhof, Faust, 2017. (Photo by: Francesco Galli, Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.)

The approach is slightly different in the Arsenale. Here, Viva Arte Viva becomes more fluid, with simple placards on the building’s pillars to mark the division among the trans-pavilions. From the Pavilion of The Common, bringing together artists exploring potential ways to build a community, the exhibition proceeds through the Pavilion of Earth, the Pavilion of Traditions, the Pavilion of Shamans, the Dionysian Pavilion, the Pavilion of Colours up to the Pavilion of Time and Infinity, which presents artists practicing a metaphysical approach to art making. Undeniably, along the way one encounters stunning works of art, that perhaps are not truly representative of our historical time, but that surely represent the current state of contemporary art. In the Pavilion of Traditions, Albanian artist Anri Sala presents All of a Tremble (Encounter I), 2016, a large-scale wall drawing with a moving roller converted into a steel comb music box activated by the drawing‘s different patterns. It explores the sculptural potential of sound, as well as the relationship between the physical work and the context in which this is situated.

Just a few meters after, in the Pavilion of Shamans, the exhibition leads you into the monumental installation by Ernesto Neto, There Is a Forest encantada inside of us, 2014. It consists of a kupixawa, a space for gatherings and celebration in the culture of the Huni Kuin, indigenous people of Brazil and Peru. During the opening week of the Biennale, Neto’s sculpture also functions as a space for a sensory and physical encounter with Huni Kuin culture, hosting a performance made by some members of the tribe who invite people to participate to their rituals and to imagine through such rituals, herbals, sounds and aromas a radical societal change.

Ernesto Neto. | Encounter with the Huni Kuin – Boa Dance conducted with the Huni Kuin performance.

(Photo by: Italo Rondinella, Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.)

Nevertheless, the quivering feeling of the unknown that is typical of any journey dissolves easily in front of the extreme rationality of the display, and of the ubiquitous and hyper-descriptive captions punctuating the whole exhibition. Presented as an exclamation, and a “passionate outcry for art and artists”,Viva Arte Viva turns out as the nostalgic representation of artists’ utopias, intuitions and aspirations. A nostalgia Christine Macel seems to be aware of: “The artists’ interpretations hinge on forms that reflect the concerns of the civil society. After all, Art may have not changed the world, but it remains the field where it can be reinvented”. Even in its content, Viva Arte Viva prioritises the linear and notional evidence of each specific case (a specific medium or a specific genre) to the social antagonism and processual contamination that yet inform such different art movements and approaches. No politics, no racism, no gender-related issues are really tackled in Macel’s exhibition, although it proposes to celebrate art as “the last bastion” to safeguard the idea of a potential neo-humanism. Real opportunities to properly encounter the microcosms (and humanisms) of each artist are offered more through the parallel projects than by the exhibition itself. For instance, the project Tavola Aperta (Open Table) consists of a series of meetings organised every Friday and Saturday during the six months of the Biennale. Different artists meet visitors for a casual lunch and discuss their practices directly with public. Furthermore, All Tavola Aperta events are filmed and streamed on La Biennale’s website.

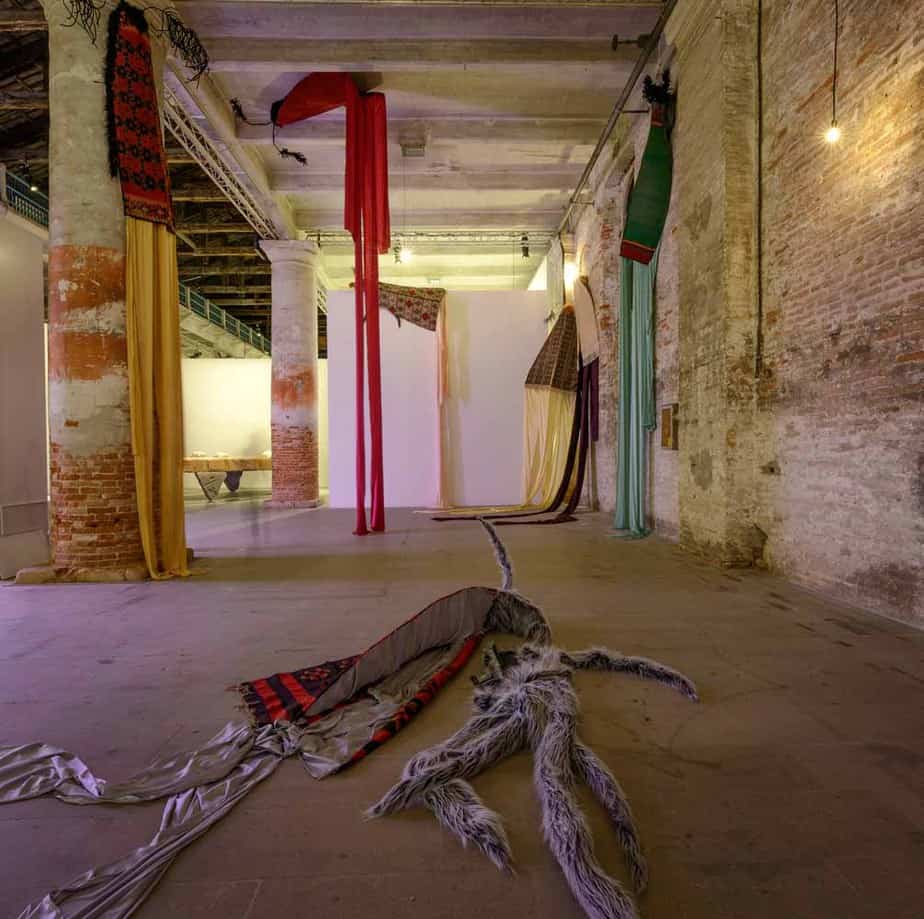

Petrit Halilaj. | Do you realise there is a rainbow even if it’s night!?, 2017. | Qilim/Dyshek/Jan carpets from Kosovo, polyester, flokati, chenille wire, stainless steel, brass dimensions variable.

[From Left] Mladen Stilinović. | Artist at Work, 1978. | eight silver gelatine prints, 2017, 28.5 x 38.5 cm, 40 x 50 cm.

Mladen Stilinović. | Artist at Work (again), 2011. | two inkjet prints, 2017, 40 x 50 cm and 50 x 60 cm.

(Photo by: Francesco Galli, Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.)

ITALIAN PAVILION. | Giorgio Andreotta Calò, Untitled (La fine del mondo), 2017.

(Photo by: Jacopo Salvi, Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia.)

All around, in the national pavilions, the biennale gets surely more political. In the German pavilion, artist Anne Imhof awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation with her performance titled Faust, 2017. A highly cinematic, emotionally brutal and visually stunning composition of bodies alternatively lunging atop glass platforms with metal grids, dancing aggressively among the public, humiliating or caressing each others. Indeed, it is a revolutionary work for it literally opens the German pavilion to the wide open space of the Giardini, being most of the walls and the entire flooring of the space covered with glass structures. Such transparency inevitably makes visitors feel like they are both observers and actors. Yet, the performance also seems to say something else, for it includes two guardian dogs barking in a glass tank just outside the space, warning everybody not to step in. Imhof’s work beautifully points out the socio-political ambiguities of humanism in present times, mingling together the human need to search for an encounter with the obsession to constantly protect the border between the self and any possible ‘Other’. Another striking contribution worth to be mentioned is surely Erwin Wurm’s at the Austria Pavilion. Humble, everyday objects are re-assessed by the artist more in their functions than in their forms as the public is invited to ‘activate’ the sculptures by following simple, hand-written instructions placed next to the objects. This way a luggage becomes a poufs to sit atop of and meditate; the pic-nic table of an old camper van becomes the support to hold one’s own head and think about one’s own virtues and sins; a kitchen island becomes a platform for a two-person meeting and conversation.

Finally, at the Italian pavilion Giorgio Andreotta Calò presents a beautiful environmental installation which covers half of the pavilion total space. Untitled (La Fine del Mondo), 2017, takes as inspiration a book by seminal Italian philosopher Ernesto De Martino who focused his lifetime researches on the significance of religion and magic in the making of communities. Arisen in deep dialogue with the architectural context in which it is situated, and reminiscent of Arte Povera’s techniques and methodologies, Calò’s work uses simple elements like water and mirrors to generate a sublime play of doubles and misleading semblances with those elements like ceilings and pillars which constitute the pavilion itself.

Vanessa Saraceno is a researcher and independent curator based in Rome. In her practice-based research, Vanessa explores the potential of socially-engaged art projects in challenging the political and economic structures that shape the way we live together in contemporary urban environments.