I’ve always been a big fan of Bock’s creative practice, and Ki Smith Gallery on the Lower East Side is situated in one of NYC’s coolest neighborhoods, so it’s pretty much the bee’s knees too. Hence, it seems kind of unusual for me to have made absolutely no preparation for this show at all. I had made no effort whatsoever to either read the press release or speak to the artist; I just like the guy and the gallery, so I figured I’d wing it—modern Americana style.

So, when I slipped into the gallery under the radar and under the half-shut corrugated metal roll- down gate on a day that Ki Smith is traditionally closed, I kind of knew that this review was going to be a serious case of infracted journalistic raw-dogging. A brief chat with the curly- haired steward commanding the desk up front lifted my spirits, though, and our quick conversation turned out to be the perfect amuse-bouche as I eventually moved through the artist’s most recent paintings for the main course.

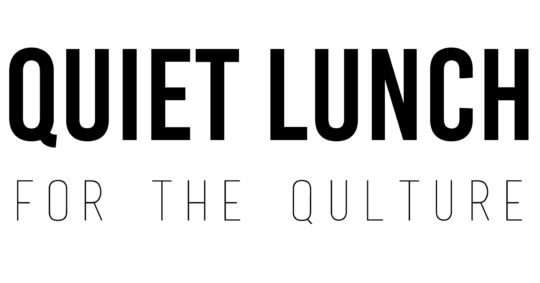

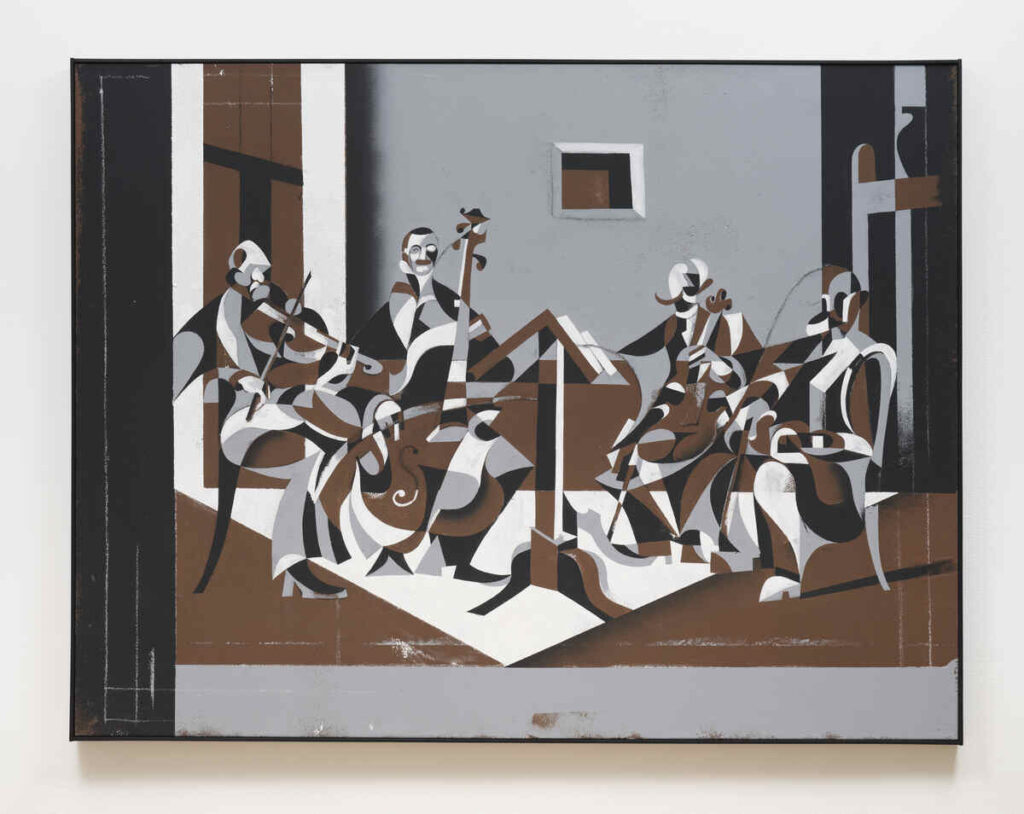

My surface impression was instant joy in the obvious references to German Expressionist film. I’ve always been a big fan of that stuff. Sometimes I think the real star of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari wasn’t the doctor—it was the wallpaper. Those wild zigzags and crooked doorways basically invented the modern painter’s emotional vocabulary. If the cinematic weirdos of German Expressionist film taught us anything, it’s that if your world feels off-balance, you might as well represent it that way.

So that’s what I initially believed this show was—a foreign visual language Bock had hijacked to communicate the uncomfortable socio-political unease of the twenty-first century, which just so happens to effortlessly parallel the awkward goings-on of the German Weimar Republic from about a centurial hop back in time. Perhaps that’s what Bock had purposefully hidden in his distorted subtext—a history repeating itself… only this time with better coffee and worse rent.

And then I read the press release.

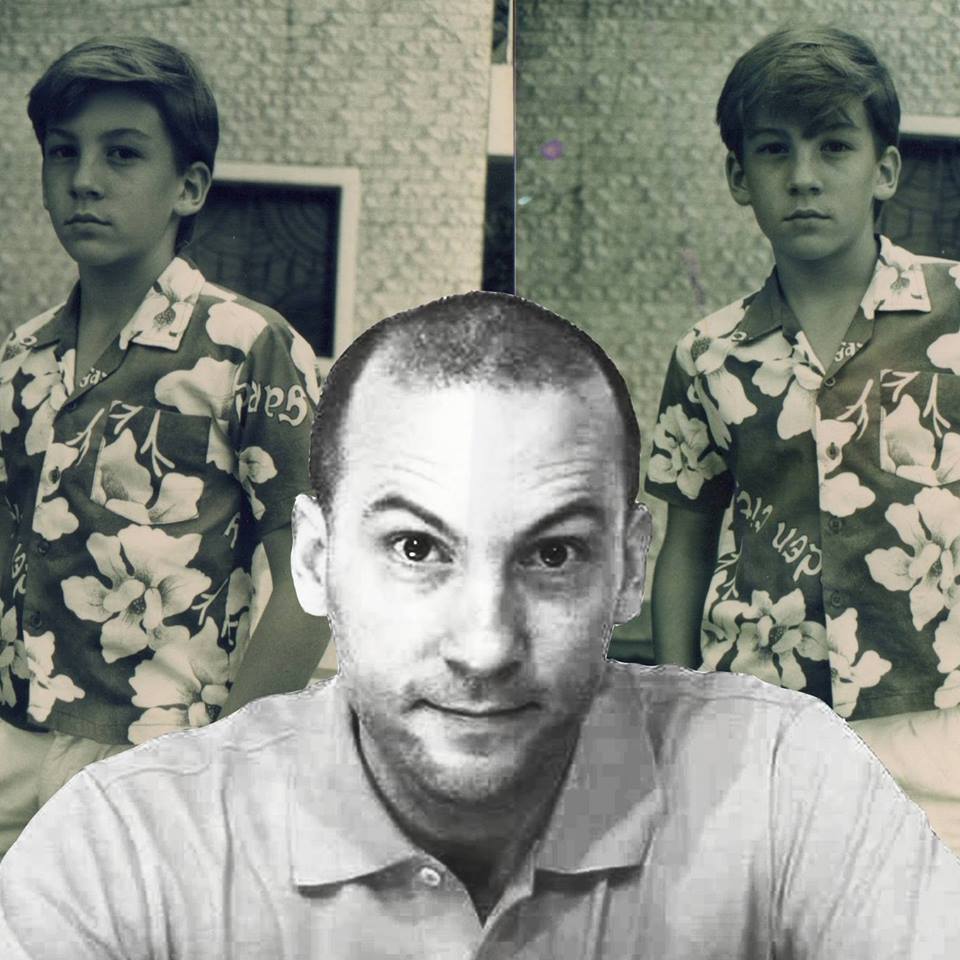

Apparently, my first impressions weren’t too far off the mark. The show is titled LICH, based on the artist’s journey to and brief residency in this quintessential German town, where he had the opportunity to retrace his complicated ancestral past.

There’s something endearingly grad-seminar about the PR statement, which is composyed entirely of remarks by the artist. It’s a mix of moral outrage, historical citation, and the lingering suspicion that underneath his ubiquitous ski-mask persona may be the bastard wilding stepchild of Twentieth-century social critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin.

“There is no document of civilization that is not also a document of barbarism…”

— Walter Benjamin

Which sounds like something you’d find carved above the entrance to a liberal-arts time machine. But then Bock is a visual artist, so let’s roll around in the mud of that rather than wade through the pseudo-psychological mire of my subjective philosophical interpretation.

The paint is meaty. The surface is intentionally naughty. The last time I had the pleasure of seeing a Bock exhibition, there were crisp edges to the rendering of images, a sharp polish to his lines, and clear color delineations. There’s little of that here. Whether it’s the horses, Jan. 6th, or the Brothers Grimm, it all has a rough and edgy grit of purposeful, sloppy brushwork to the approach. Perhaps it’s a double-down on the idea that even though history may be repeating itself and we can clearly see it unfolding before our bleary eyes, that doesn’t make it any less confusing to digest or identifiable in flavor.

“What makes this exhibition so urgent is that it confronts the descent into authoritarianism we are witnessing in real time worldwide. The brilliance of LICH lies in Ryan Bock’s multi-layered narrative architecture and execution: compositionally referencing German Expressionism and Czech Cubism to elevate an anti-fascist conversation within the art historical canon, while simultaneously deploying propagandist imagery, Grimm’s folktales, personal displacement narratives, and the very mechanics of myth-making to situate his warning against cyclical and contemporary ultranationalism within a transhistorical and transcultural framework.

This approach masterfully allows the viewer art historical, literary, and self-reflexive entry points to critically and constructively discuss today’s divisive and incendiary politics, as well as reevaluate the narratives that shape their own identities and prejudices, in a time when the very construct of communication is under threat.”

— Celine Cunha, Curator of LICH

Overall, I can easily see this exhibition taking up space at the Museum of Modern Art one hundred years from now—as a testament to the mood of twenty-first-century popular and political culture, giving off vibes of a zeitgeist on the precipice of fundamental change. Whether that change will be in reaction to, or in keeping with, historical tendency is yet to be known—but the feeling that Bock understands the tenuous nature of human behavior is obvious and leaves me nervous about what’s to come from an age both familiar with the atrocities of the past and unfortunately likely to repeat its same mistakes.

“LICH as any exhibition that’s come before it should act as another step up in my evolution. Hopefully, each step I take brings me closer towards being understood, not only as an artist but as a human being. As long as I can continue to challenge myself and the world around me via authentic and genuine expression and inspire others to do the same, my career will have been a success…”

— Ryan Bock

Five stars for Ryan Bock – LICH curated by Celine Cunha @ Ki Smith Gallery, on view through November 23rd.

Jason Patrick Voegele is an international art critic, reformed gallerist and art consultant based in NYC.